An endgame in Ukraine may be fast approaching

After two years of war, an increasingly sombre mood has swept over Ukraine and its supporters in the West

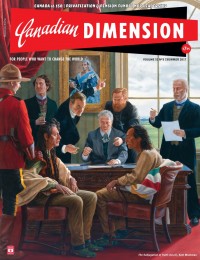

The military situation today is very different from that of a year ago when commentators were predicting that final victory was within Ukraine’s grasp. Photo courtesy the 148th Separate Artillery Brigade/Armed Forces of Ukraine/X.

It is probably fair to say that nobody has done a very good job of predicting the ups and downs of the war in Ukraine, which this week marks its second anniversary. Initially, analysts overestimated the power of the Russian army, believing that it would quickly defeat Ukraine. When that turned out to be untrue, they then made the mistake of underestimating Russia, believing that Ukraine was bound to triumph. Now, the circle is turning again, and a spell of gloom is falling down over the West, as it faces the reality that Russia has not collapsed under the weight of sanctions, that the Russian army is showing no signs of disintegration, and that it is Ukraine that seems to be coming off worse in recent battles. The question we now face, therefore, is whether the current gloom is justified or is yet another misperception of reality.

The evidence would suggest that the former is possibly more likely than the latter, although we can’t be entirely certain. The military situation today is very different from that of a year ago when military commentators were confidently predicting that final victory was within Ukraine’s grasp. Huge hopes were placed in an offensive operation planned for the spring and summer of 2023. Its direction was widely known—too widely known, in fact, as it gave the Russians lots of time to prepare. The Ukrainians were to strike southwards in Zaporozhe province in order to reach the Black Sea and Sea of Azov, cutting Crimea off from Russia, and isolating it from resupply. Russia, it was believed, would then be forced to concede defeat, and Putin might even be ousted from power by disgruntled Russian elites, determined to save what they could from the debacle.

While some military analysts thought that this objective might be a bit much for Ukraine, they nonetheless expected the Ukrainians to make some notable advances. Optimism ran high. It continued even when the much-advertised offensive ran immediately into major difficulties after it began in early June. The narrative changed. Pundits now argued that capturing territory was not important. What mattered was destroying the enemy’s army, and that the Russians were supposedly suffering far greater casualties than the Ukrainians (a claim for which no strong evidence was ever produced). The calculus of attrition favoured Ukraine, went the argument. Backed by the massive economic power of the West, Ukraine could not but triumph over the much weaker Russia.

It was not to be. By the start of October, the Ukrainian army had abandoned its offensive, having advanced at most about 10 kilometres in a couple of small sectors of the front. The massive stocks of ammunition that had been piled up for the offensive had been expended. Meanwhile, the Russian army, far from losing the attritional battle, had become stronger than before. Buoyed by large numbers of new recruits, increased military industrial production, and weapons supplies from Iran and North Korea, by mid-October the Russians were attacking along the approximately 1,000 kilometre long front line. Last week their attacks finally bore major fruit in the form of the capture of one of the most strongly fortified of all Ukrainian positions, the town of Avdiivka. Further Russian advances are now widely expected.

Coming on top of the failure of the Ukrainian summer offensive, the capture of Avdiivka has reinforced an increasingly sombre mood among pro-Ukrainian politicians and commentators in the West. Talk of a Ukrainian victory has almost entirely disappeared. Even the most optimistic analysts speak only of Ukraine holding the line in 2024 and going back onto the attack in 2025. Even that, though, is dependent on the West increasing its supplies of weapons to Ukraine, as well as on the Ukrainians themselves sorting out their manpower problems. At present, though, the flow of weapons is slower than it was a year ago, while the Ukrainian army is struggling to conscript an adequate number of its citizens. Military recruiters have been recorded admitting that they have fallen far short of their conscription targets. Those that they do round up are often aged and, as even pro-Ukrainian commentators admit, “are in poor physical shape and have health issues that limit their ability to fight.” A new conscription law is currently going through the Ukrainian parliament, but even if it passes, it will take months for its effects to be felt, and there is no guarantee that it will succeed in enabling the Ukrainian state to drag more of its reluctant population into military service. American military analyst Rob Lee comments that “Ukraine faces two acute issues right now: a lack of ammunition and a lack of infantry.” That’s pretty much the definition of an army that is losing.

On the other side, Russia also has problems. Its losses are heavy, and while it has demonstrated an ability to win local tactical victories, it has yet to prove that it can convert these into broader operational success. Meanwhile, it continues to use up supplies at a faster rate than it produces them, a process that cannot last forever, as eventually stocks will become exhausted. While Russia fires many more artillery shells than Ukraine, it doesn’t fire as many as it used to. This leads some to argue that “Russia’s domestic ammunition production capabilities are currently insufficient for meeting the needs of the Ukraine conflict.”

Nevertheless, increases in Russian arms production mean that Russian industry is currently outproducing the entirety of NATO in most crucial areas, such as artillery ammunition, tanks, and drones. There is no sign as yet of any substantial reduction in Russian firepower. Although Russian artillery has indeed become somewhat less active, it remains powerful, and the reduced activity has been more than compensated for by increased use of drones and large air-launched “glide bombs,” such as the 500 and 1,500 kilogram FAB bombs, scores of which were being dropped every day on Avdiivka during the final days of the battle there. At present, Russia substantially outguns Ukraine, and even if Western aid to Ukraine were suddenly to grow, it seems unlikely that it could grow so much as to bring parity, let alone the large advantage required for a military breakthrough.

Beyond that, Russia also enjoys a significant manpower advantage. Not only is its population much bigger than Ukraine’s, but it is also proving able to recruit large numbers of volunteers. According to the head of Ukrainian military intelligence, Kyrylo Budanov, Russia is recruiting about 30,000 volunteers a month, a figure that roughly coincides with official Russian claims of around 400,000 volunteers a year. By contrast, in the past 12 months, Ukraine has proven unable to gather even half that many recruits through conscription (volunteers for the Ukrainian army are nowadays few and far between). Western analysts have long claimed that one of Ukraine’s biggest advantages over Russia was a greater willingness to fight. If that ever was the case, it doesn’t seem to be so any more.

All this makes the prospects of a decisive Ukrainian victory seem very slim. Even if Ukraine can somehow regain the initiative, it seems very doubtful that it could ever gain the degree of military superiority that it would need to achieve its stated political objective of restoring its 1991 borders. It would be unwise to say that that is impossible, but at present it’s very hard indeed to imagine how it could be done. Furthermore, even if it could, it would take very many years, at the end of which one might wonder what would be left of Ukraine and its population.

Given this reality, talk is now increasingly shifting from how to help Ukraine win to how to help Ukraine to force Russia to abandon its more extreme political objectives (neutrality and demilitarization of Ukraine) and accept a more limited outcome. This might involve Russia keeping whatever territories it should happen to control at the time of a ceasefire, while allowing Ukraine to keep open the option of eventually joining NATO. This is a more plausible objective for Ukraine than restoring its previous borders. But it must be noted that even this would require years more fighting, so as to convince the Russian leadership that it can’t achieve anything greater and to cash in what winnings it has. Again, the price that Ukraine would have to pay for such a prolonged war would be enormous. One has to wonder if it would be worth it.

As things stand, two years into the conflict, the war’s outcome remains uncertain, although some things are becoming clearer. The chances of a decisive Ukrainian victory now seem very low. What remains less sure is whether Russia has the ability to win such a victory itself. There is little indication of a sudden breakthrough of the Ukrainian line and a return to rapid maneuver warfare. There is, though, some chance that continued pressure over the next few months may cause something somewhere to break on the Ukrainian side. But there is also a possibility that the Ukrainians will somehow cling on, and that a combination of renewed Western aid and a successful mobilization of Ukrainian manpower will then enable the Ukrainians to restore a degree of military balance, producing a long-lasting stalemate.

The next few months are of decisive importance, as they are likely to determine down which of these paths the war is headed. In the meantime, some long and bloody fighting lies ahead.

Paul Robinson is a professor in the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Ottawa and a Senior Fellow at the Institute for Peace and Diplomacy. He is the author of numerous works on Russian and Soviet history, including Russian Conservatism, published by Northern Illinois University Press in 2019.

_in_The_Hague_600_400_s_c1.png)