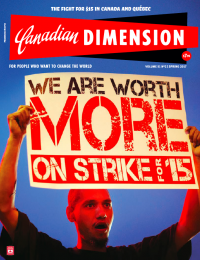

Direct action wins at Frite Alors!

A lot of the labour movement knows that there are serious problems with the way unions have developed in Canada. If you say “we rely too much on the grievance procedure,” people will nod sagely. If you say “we need to find a way to get back to our roots and use organization on the job to pressure management into making concessions,” a lot of people are going to agree with you. But, in practice, there are few examples of unions thinking and organizing outside of the “labour relations” box in Canada. It is easy to talk of “new ways of organizing,” but when the heat is on and people are getting fired for union activity, the range of realistic options narrows and you find out what a union is made of. If a union can protect their members it is an effective union. If it can advance their members interests they are a good union.

This was made clear this summer in Montréal, when a member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was fired in a Poutine Shop. She had been organizing at her job for better conditions and pay increases. What they weren’t asking for is union recognition or a contract. Several members from the Montréal Branch of the IWW promptly entered the business and sat down occupying the building. This effectively stopped business. Within a few hours word was getting out and the bad publicity was getting to the owner. By the end of the day the sister had her job back. No paperwork, no grievance steps, no arbitration hearing.

The way most unions, including the unions I have worked for, would handle this is they would have filed an Unfair Labour Practice complaint, or ULP, if they were organizing the place or a grievance if it was under contract. This would then be heard by the appropriate panel, damages would be assessed, there would have been a payout and maybe the union member would have gotten her job back. This process would have taken a few months to a year to settle.

In this case there were calculated risks taken. Several members risked arrest, the union risked escalating too fast for more neutral workers in the shop to handle, and the member in question risked losing her job by organizing. What reduced the risk was that she was a trained organizer (the IWW has a pretty intensive organizer training program), she had a lot of experienced organizers to rely on for outside support, and she had an organization that had confidence in its members. Most importantly, though, she had the conversations about getting fired for organizing with her co-workers before it happened and made it clear what could happen in the course of organising.

That last ingredient is key, you can get fired for organizing, and when that happens, you have to fight it. When you fight it there is no guarantee of success. The labour relations system we have is so appealing because it looks like the safer bet but it is actually often less effective than direct action. A legal dispute also has a tendency to mask the political content of what is going on. Even in a grievance it isn’t really about an aggrieved party and a violation of the contract. What is actually going on usually is a power struggle between a worker and their boss. The labour relations system exists to hide that power struggle behind a façade of reasonable arguments. As soon as we forget that it is a power struggle we become weaker and that affects our ability to advance our members interests.

Nick Driedger is a member of the Industrial Workers of the World who lives in Athabasca Albera.