The ‘strategic voting’ election and its undemocratic consequences

Canada’s voting system is a pre-democratic hold-over and it remains in use because it serves those that benefit from it

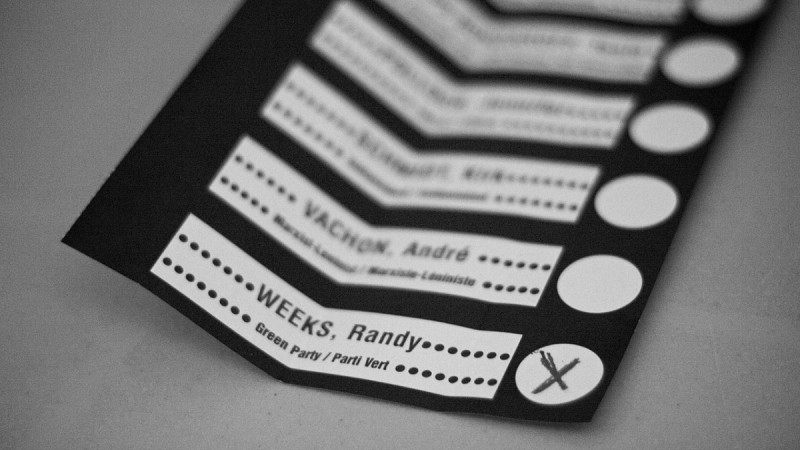

Photo by D’Arcy Norman/Wikimedia Commons

There are so many headline takeaways from the 2025 federal election: the loss of what had appeared to be a sure-fire Conservative victory, the dramatic resurrection of Liberal party fortunes under new leader Mark Carney, and collapse in voting support for the country’s third parties: the Greens, Bloc Québecois, and especially the NDP. The impact of Trump’s threats to annex Canada and impose harsh tariffs on Canadian goods has been clearly underlined by most commentators as driving these results. But less attention has focused on just how Canada’s electoral institutions made responding to such threats much harder and less democratic than they should be. If we look beyond the headlines, the key challenge facing voters in this election was really all about strategic voting. Canada’s single-member plurality (SMP) voting system simultaneously amplifies the pressure for voters to vote strategically while denying them adequate information to do so effectively. And the real shame is, there would be no need to vote strategically at all if we used a more representative, inclusive and ultimately democratic voting system—in other words, some form of proportional representation.

Let me backtrack to sketch in a bit more about what strategic voting is and why it dominates elections under our voting system. The whole point of representation in a supposedly democratic system is that people should vote for what they want to see taken up politically. This is what voting theorists call a ‘sincere’ vote. But the voting system you use can influence whether people decide to vote sincerely or not. When you vote in an SMP voting system the results are ‘winner take all’ for the candidate who achieves the most votes. If there are just two in the running, one will probably attain a majority. But with Canada’s multiparty system, many seats are won with just a plurality (more votes than any other single candidate but not a majority). Now voters have to weigh up not only whether voting sincerely would get them what they want but whether it might inadvertently help elect someone they really don’t support. This is where strategy comes in. Let’s take a concrete example. In the Nanaimo—Cowichan riding the incumbent NDP MP was defeated by a Conservative who secured just 35 percent of vote, while the Liberal, Green and NDP candidates secured 28, 18, and 18 percent, respectively. Prior to the election, a voter opposed to the Conservatives had to ask themselves, which candidate can win? Given that the riding had a history of electing NDP and Green candidates it stood to reason someone other than a Conservative would likely triumph. But which non-Conservative was the best bet was not obvious, as the results clearly demonstrate.

The problem with strategic voting is that, by design in our SMP voting system, voters lack the necessary information to make strategic choices. To know which party could best defeat the Conservatives in Nanaimo—Cowichan voters would need riding level polling information about who other voters intend to vote for, which would be prohibitively expensive to produce. Without this, voters have to rely on their gut level sense of who has the advantage, which is usually based on visible local campaign signage, national level polling, and any cues they might be getting from their preferred party. Days before the election reports were rife on social media of NDP organizers desperately trying to communicate to voters in ridings with incumbent NDP MPs that the NDP was actually the strategic choice to defeat Conservative candidates in those places, not the Liberals. But many voters that used widely publicized national polls as a guide chose the Liberals instead, contributing to NDP losses and Conservative wins.

There have been calls to adopt less sweeping reforms to Canada’s voting system. For instance, Justin Trudeau ran in 2015 promising to “make every vote count” by replacing SMP with something else. The something else he wanted turned out to be the majoritarian ranked ballot, used in Australia where it’s known as the Alternative Vote. It’s easy to see how the use of the ranked ballot might have offered non-Conservative voters in Nanaimo—Cowichan some options in terms of avoiding splitting their vote but, on the whole, this voting system also tends to over-represent the biggest parties, leave many voters without representation, and create majority governments based only on a minority of the votes. So, it leaves a lot of the negatives associated with strategic voting in place.

If adopting PR would make voting more straightforward and less negatively strategic, why don’t we do it? The short answer is party self-interest. Basically, our two main traditional governing parties at the federal level don’t want PR for the reasons set out above—it would better represent what voters say with their votes and end the practice of awarding majority governing power to a party with only minority voting support. Under PR parties would likely have to share power and such an arrangement would force greater transparency on government decisions and make the backroom financial deals that sustain both parties harder to carry out. PR would also allow voters to make the parties they vote for more accountable because they would have an ability to choose a likeminded alternative. Some politicians and misguided political scientists try to argue that we haven’t adopted PR because its fails to match Canadian values, or that it would be confusing and lead to unstable government. But they produce no credible evidence to back such assertions. The truth is, claims like these are typically just post hoc justifications for a status quo that serves political interests rather than the public good.

The 2025 federal election demonstrates the failings our electoral institutions from a democratic perspective. But here it is important to remember they were never created or kept in place with democratic objectives in mind. Canada’s voting system is a pre-democratic hold-over and it remains in use because it serves those that benefit from it. There have been 10 voting system reforms at the provincial level in Canada since Confederation, demonstrating that our political elites are only too happy to change the rules (and change them back) when they feel threatened and/or it might serve their interests. Thus changing the voting system at the federal level is not merely a technical question but one of bringing more democratic substance into our politics. That’s going to require a movement for democratic reform. Left to their own devices, not surprisingly, our dominant governing parties would prefer Canadian voters remain locked in a straitjacket of strategic voting options limited to tweedle-Con and tweedle-Lib.

Dennis Pilon is a former Canadian Dimension Editorial Collective member. He is currently a Professor and Chair of the Politics Department at York University. His research on Canadian democracy and voting system reform can be found here.