Canadians are on year three of a people’s recession

Why your bank account feels the squeeze while GDP rises

Photo by Ian Muttoo/Flickr

A new Deloitte report is projecting 1.3 percent GDP growth for Canada this year. The same report says that as long as Donald Trump keeps the CUSMA carve-outs in his tariff plan—meaning that most of the goods we export to the United States won’t face tariffs—we can look forward to 1.7 percent growth next year. This would mark a return to the growth rates we saw in 2023 and 2024.

Economists seem cautiously optimistic that Canada will avoid a recession and return to a period of relative stability.

This should be great news. On paper, the economy has proved its resilience in the face of serious challenges. But why then do things feel increasingly precarious? If the economy is doing so well why are so many Canadians lining up at food banks, putting off having kids and giving up on the idea of homeownership? Why are 30 percent of us cutting down on essentials like food and heat to make ends meet? Why is it that, after years of post-pandemic growth, our wages feel more stretched than ever?

The disconnect between big economic indicators and Canadians’ day-to-day experience is a gap our political leaders seem unable or unwilling to bridge. Our collective sense of economic malaise was infamously dismissed by Chrystia Freeland late last year as a ‘vibecession.’

Indeed, parliamentarians have gotten in the habit of telling us that everything is basically fine—we just need to live within our means, blame immigrants, and cancel Disney Plus. It hasn’t occurred to our political elites that the economic indicators might be missing something.

That something is the $3 trillion debt bomb quietly ticking beneath Canada’s thin veneer of stability.

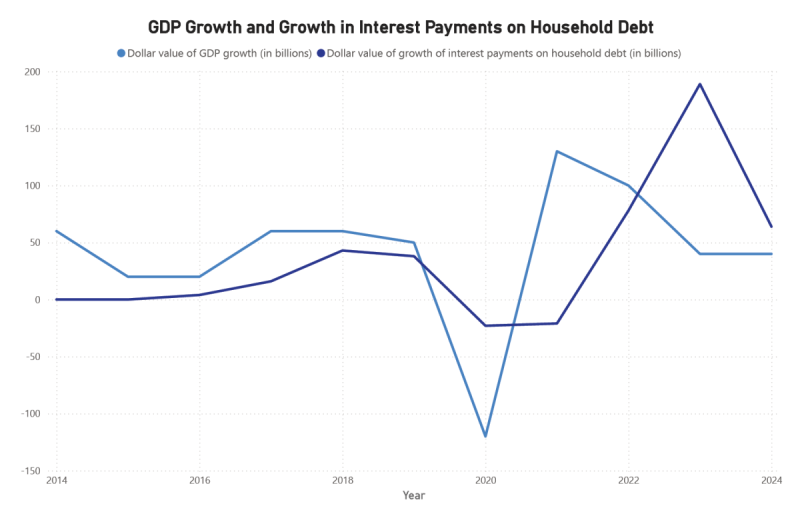

Last year’s growth rate was 1.6 percent, totalling $40 billion in value. In that same period interest payments on household debt increased by $64 billion. In other words, the value of national economic growth was eclipsed by the rise in interest payments.

This hurts everyone. Well, everyone who isn’t a banker.

High debt servicing costs means people have less money to spend and businesses have less money to make. When debt payments are so high that money is pulled from the circular flow of the economy beyond the rate at which the economy grows, production and consumption (that is, the real economy) shrinks.

Economists call this process “debt deflation” and we have been experiencing it for the last three years.

While official indicators have painted a picture of modest prosperity, month after month Canadians have seen less money circulating in the economy.

This is not a matter of perception: we are getting poorer even as the economy grows. StatsCan data on GDP growth and interest payments on household debt (75 percent of which is mortgage debt) show this pattern very clearly.

This graph underestimates the debt burden we carry. It does not include increases in interest paid on national debt, provincial debt, or debts owed by the private sector. The full debt deflation picture is likely much worse.

If this trend is allowed to continue, it’s not just annual economic growth that will be devoured by high finance, it’s all national production. Virtually all economic output is on track to be earmarked in advance by our creditors.

The people doing the lending argue this kind of analysis misses the point. They say that interest payments cannot be separated from some arbitrarily delineated ‘real’ economy, that banks use the interest they collect to reinvest in the nation’s productive capacity. While this is how things work in undergraduate textbooks—banks are said to lend to businesses to upgrade their technology or expand their operations—it is simply not how lending operates in practice.

Instead of using their profits to grow businesses banks have demonstrated a strong preference to issue less risky loans, the majority of which are for the purchase of residential and commercial real estate. The simple fact is that the lion’s share of lending occurs primarily to facilitate property title transfers. This has the dual effect of deepening our debt burden and juicing housing prices.

In the words of economist Michael Hudson, banks pretend their profits are infused into the economy, “creating jobs and financing new factories and other means of production,” but “the reality is that bank loans do not fund direct investment and employment. They extract debt service while inflating asset prices to provide ‘capital’ gains.”

The counter-productive nature of these financial games is summarized by former UK Financial Services Authority Chairman Adair Turner who described much of global finance as “socially useless.”

Even decidedly pro-banking institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) have published research showing that a financial sector over a certain size is a drag on growth that raises the risk of economic crisis. Reviewing a wide range of national and historical contexts, these studies suggest the threshold for “too much finance” is crossed when private lending amounts to 80-100 percent of GDP.

For reference, Canada’s household debt is roughly 150 percent of GDP.

So, yes, Chrystia Freeland was right. The economy is growing. But what Ottawa misses is that our growth is driven by “socially useless” industries. Banks and landlords account for 15 and 20 percent of GDP growth, respectively, making real estate speculation the single largest driver of growth in Canada—significantly larger than manufacturing, retail, or oil and gas.

In essence, the Canadian economy is ‘growing’ not by producing more, but by charging more to access what already exists.

Ultimately, debt-fuelled speculation on housing markets is not growth, it is a con.

In 2022 our economy turned on itself: banks and real estate speculators began feasting on workers and industry, causing immense harm to our productive capacity. The economy of production and consumption—the economy we all live in—began to be eaten up by interest payments on artificially inflated asset prices.

Since then, an ever-larger share of the productive economy has been claimed by bankers, private equity, and other rentiers every year. A situation now exists where what our leaders call ‘growth’ is nothing short of economic auto-cannibalism.

Despite rosy post-pandemic GDP figures, Canadians have seen rising interest payments outpace growth. The result has been severe debt deflation. We have found ourselves doing more with less. An ever-increasing debt burden has pushed us into an effective recession, one masked in the official metrics by a massive bubble in the housing market.

There is a limit to this, a point at which the debt that is imposed on us becomes simply unpayable. If we allow ourselves to come to that point, the bubble will burst. The only question is what will be left of the real economy when it does.

James Hardwick is a writer and community advocate. He has over ten years experience serving adults experiencing poverty and houselessness with various NGOs across the country.