Canada’s debt time bomb

The next crisis will be blamed on debtors, but it was engineered by speculators and their allies in government

Photo by ginza_line/Flickr

This year, Canada’s household debt climbed to $3.07 trillion, topping the G7 for the 15th consecutive year. With debt—including mortgages, auto loans, and credit cards—growing faster than incomes, this trend shows no sign of slowing. As individuals and small businesses fall behind on loan payments there is evidence that this enormous burden is already straining Canadians’ finances. As a society, we are in danger of insolvency. A sharp drop in employment—potentially triggered by tariffs, rising mortgage costs, a slowdown in lending, or sudden price shocks—could easily push overleveraged families into bankruptcy, with destabilizing consequences for the entire economy.

This historically unprecedented debt burden is carried by people struggling to keep up with decades of rising living costs, stagnant wages, and shrinking social services. Yet if and when the crash comes, ideologues in Parliament and the media will rush to blame already beleaguered debtors. Canadians merely trying to get by will be labeled profligate and irresponsible, accused of taking out loans they could never have afforded. The finger wagging has already begun over at the Globe and Mail.

But the reality is that this debt (75 percent of which is mortgage debt) was inflicted upon us. It is odious debt pressed onto our balance sheets by real estate investment trusts, banks, and landlords—powerful financial interests that have spent decades flooding the market with artificial demand and forcing housing costs to dizzying new heights.

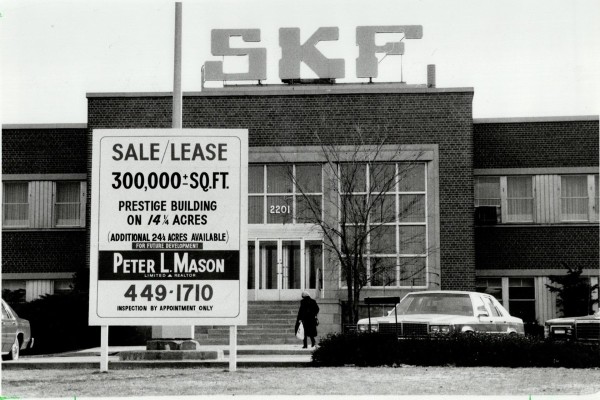

While the mechanics of investor-driven housing bubbles may seem complex, they are neither new nor mysterious. History and economics textbooks are full of examples where real estate speculation led to calamity. Among the most notable is late-20th century Japan. In 1986, Japan faced weakening international demand for its industrial exports. To avert a recession, the central bank slashed interest rates while the government encouraged easy credit. Instead of investing in their operations, businesses poured their low-interest loans into real estate. This surge in demand, driven by an unscrupulous investor class, sent property values soaring and sparked a land mania. At the peak of the bubble, Tokyo’s Imperial Palace was reportedly worth as much as all of California.

(This comparison finds a striking echo today in Canadian TikTokers who juxtapose listings for run-down houses in Hamilton and Kitchener with European castles and Caribbean islands selling for the same price.)

As in Canada today, soaring real estate prices drove Japanese households deep into debt. At the peak of the 1990 housing bubble, Japanese citizens carried a debt burden of ¥325 trillion—equivalent to $3.8 trillion in inflation-adjust Canadian dollars.

The way housing speculation translates into rising household debt may be lost on op-ed writers at the Globe and Mail or party apparatchiks like Chrystia Freeland, but this dynamic has shaped the lives of everyday Canadians since the turn of the millennium.

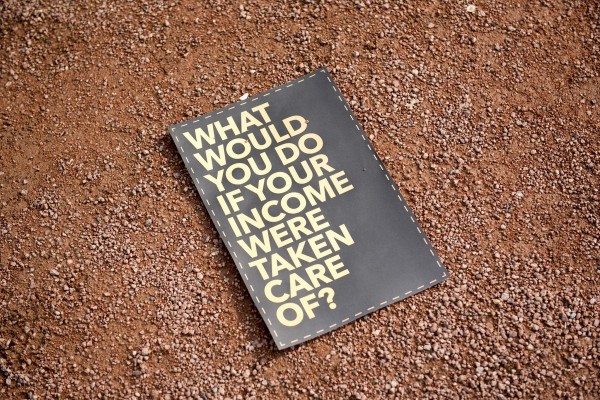

As investors drove up housing prices with the enthusiastic backing of all levels of government, the rest of us were left paying for homes we couldn’t comfortably afford. An ever-growing share of our incomes went to financial institutions—either directly through mortgage payments or indirectly through rent, which almost always covered someone else’s mortgage. Rising housing costs eroded our ability to absorb the effects of chronic inflation and stagnant wages. Saving became nearly impossible, and unavoidable expenses like vet visits or car repairs had to be financed through debt. Soaring auto loans and credit card bills show that, for many, debt has become essential to survival.

And now, with unemployment rising, many of us will not be able to pay it back.

In Japan, the housing bubble finally burst not due to rising unemployment, but because soaring home prices pushed the economy to the brink of uncontrolled inflation. To avert total disaster, the Bank of Japan raised interest rates, making mortgages unaffordable overnight. Investors rushed to sell properties they could no longer sustain, and housing prices plummeted. To prevent widespread defaults and foreclosures, banks were forced to restructure loans—a relief that will not be extended to us. The bubble’s collapse triggered a stock market crash that wiped out trillions in wealth, and even 40 years later, the Japanese economy has yet to fully recover.

For us, it will be different. In the short term, we are facing the possibility of widespread personal bankruptcy. The ripple effects of even limited debt repudiation could be severe. Not only will individual households suffer, but with the government on the hook for many of these mortgages, taxpayers will almost certainly find themselves paying for the banks’ bad investments. As in Ireland in 2008, financial elites are poised to walk away from any potential market collapse with their riches intact, leaving the rest of us to endure years of gruelling austerity.

Mark ‘13-years-at-Goldman-Sachs’ Carney cannot be relied upon to hold financial institutions accountable for their predatory lending practices, as Iceland did when their banks misbehaved. Instead, he is likely to take the same stance the Democratic Party took after the Great Financial Crisis (which is the same stance the European Commission adopted during the European sovereign debt crisis): he will assert that our collective prosperity depends on paying the bankers who engineered the crisis in the first place, a position described by economist Michael Hudson as “a veritable Stockholm Syndrome” in which debtors are asked to “identify with their financial captors.”

We cannot allow ourselves to be taken in by these old, familiar fairytales. We cannot allow Canada’s systematically immiserated citizenry to be scapegoated while financial elites use the crisis to buy up distressed assets and deepen their control over our lives. We must loudly and publicly reject austerity, refuse creditor bailouts, and demand that the ones responsible be held accountable. We must be prepared to take to the streets and insist that housing markets be restored to sanity and not re-inflated through massive giveaways to predaceous investment firms.

And if the crash does not come this year, if the economy proves its resilience and weathers this storm with its ever-expanding burden of household debt intact, then perhaps we can take this brush with disaster to heart and start to deflate the housing bubble in a controlled manner.

Regardless, if we want to keep our homes from being used by billionaires as financial playthings we must make full-throated demands for the removal of hedge funds, REITs and other speculators from the housing system. We must insist on massive federal investments in publicly built and owned housing as well as the cancellation of the odious debts that were inflicted on the people of this country.

Say it with me: the rentier economy must end.

James Hardwick is a writer and community advocate. He has over ten years experience serving adults experiencing poverty and houselessness with various NGOs across the country.