Would a maximum wage law work for Canada?

The idea of a maximum wage is the logical counterpart of a minimum wage in ameliorating extremes in market outcomes

Illustration by Notable.ca

The idea of a maximum wage is the logical counterpart of a minimum wage in ameliorating extremes in market outcomes. With the global equality gap rupturing societies almost everywhere, it is a sane suggestion to find ways to help rein in the super-rich. Traditional societies used everything from the potlatch to capital punishment to limit the over-accumulation of wealth. These days, Cuba has a maximum wage law, at least on paper. There have been tentative moves in this direction in both Egypt and Switzerland. In the UK, left Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn just advocated such a cap on top incomes and worries that, with BREXIT, the highly unequal UK will become a “a grossly unequal bargain basement economy” on the borders of Europe. A recent editorial in the prestigious BMJ (British Medical Journal) delineates some of the costs:

Inequality matters because, as a robust and growing body of evidence shows, the populations of societies with bigger income differences tend to have poorer physical and mental health, more illicit drug use, and more obesity. More unequal societies are marked by more violence, weaker community life, and less trust. Inequality also damages children’s wellbeing, reducing educational attainment and social mobility.

Even the superich’s own intellectual gabfest, The

World Economic Forum held each year in the Swiss

resort town of Davos, sees wealth disparity as the

most important trend and challenge for the entire

world economy.

So would a maximum wage policy help check this trend? Probably not much in and of itself. It would be no replacement for a comprehensive reworking of the tax system in a progressive direction. This would have to involve a raising of the highest marginal tax rates to at least the 65 percent recommended by the late Tony Atkinson, whose lifetime work as an economist was the study of inequality and how to reduce it. The Justin Trudeau government is already showing it is moving in the opposite direction by backing away from its promise to close a $750-million stock-option loophole used mainly by senior executives. Of course, the most crucial change would need to be tackling the system of off-shore tax avoidance that allows “high worth individuals” and major corporations to reduce their tax bills and squeeze public finances. While perfectly doable, such an assault would take a multilateral effort, which the Trudeau Liberals have shown little appetite to participate in, let alone lead.

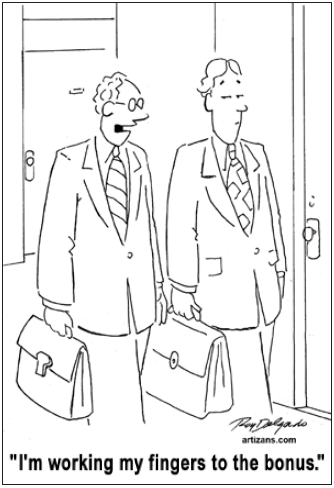

Critics of a maximum-wage tax rightly point out how difficult it would be to enforce because of how purposely muddy it is to define what a wage is for a high-end banker or other corporate CEOs. Remuneration usually comes in a package including stock options, bonuses and lavish expense accounts.

People (predominantly men) at these dizzying social heights can afford the very best in accountants and other professionals to divert or disguise their incomes.

But something needs doing. In 2015, the average annual compensation for Canada’s top-paid executives was $9.5 million. That is 193 times the average industrial wage in the country. At this rate, a top-100 executive earns the average annual Canadian wage by 11:47 a.m. on January 3. If the gap is measured against the woefully inadequate average Canadian minimum wage ($11.18 an hour or $23,256 a year), a top exec would have earned that by 2 pm January 2.

Cartoon: Roy Delgado/Artizans

One professional sport—the US-based National Basketball Association—does however provide an interesting example of maximum wage. NBA stars like LeBron James and Kevin Durant have their salaries capped at no more than 20 times what the least-well-paid NBA player makes. If such a differential were rolled out across the economy—the “relative earnings limit” approach to a maximum wage—to cover all executive salaries, the effects would be dramatic. At a minimum wage of $15 an hour (one still bitterly resisted by most of the corporate sector) the average executive salary would be a modest $300 an hour. One suspects that, under such circumstances, the lack of corporate enthusiasm for a healthy minimum wage would change quite abruptly.

A maximum wage (like a minimum wage) is no panacea, failing as it does to address both the content and conditions of work or the overall way in which society’s wealth gets distributed. However, depending where it was set and how vigorously it was enforced, it could help to revive public finances and tame the trend towards galloping inequality. Perhaps the most important effect of maximum-wage legislation would be symbolic. If the Canadian government were to undertake such a move, it would be a shot across the bow of the prevailing Ayn Rand-inspired notion that unlimited individual selfishness is what defines human existence. Such a view is coming to endanger everything from democracy to a liveable ecosystem. In an age when we are desperately in need of finding ways to live more modestly and sustainably on the earth, it would be a direct challenge to the implacable logic of growth capitalism that “enough is never enough.”

Richard Swift is a longtime activist, journalist and author. His most recent book is SOS: Alternatives to Capitalism (2014) and he is the producer of a 2013 CBC Ideas program on degrowth. The editor of the New Internationalist for more than two decades, he is currently a Canadian Dimension coordinating editor.

This article appeared in the Spring 2017 issue of Canadian Dimension (Fight for $15).