Leonilda Zurita: Growing Coca in a Fight for Survival in Bolivia

For centuries, coca has been used as a medicine in the Andes to relieve hunger, fatigue and sickness. Many Bolivians chew the small green leaf or drink it in tea on a daily basis. Much of the coca produced in Bolivia goes to this legal, controlled use. But the leaf is also a key ingredient in cocaine. The U.S. government has focused on coca eradication as a way to stem the flow of cocaine to the U.S. This war on drugs in Bolivia has resulted in violence, death, torture and trauma for the poor farmers who grow coca to survive. The U.S. government has directly funded this war, often facilitating human-rights violations and acting as a roadblock to peace in Bolivia. And the billions of dollars that Washington has pumped into this conflict have not diminished the amount of cocaine on the streets in the U.S.

Besides its traditional uses, in Bolivia coca is also an ingredient in Coca-Cola, cough syrups, wines, chewing gum and diet pills. It is sold in small bags all over the country, and is perhaps more prevalent than coffee. The U.S. Embassy’s website for Bolivia suggests that chewing the leaves can alleviate altitude sickness.

After listening to the messages, she spread out rice to dry in the sun and mentioned that her chicken had been recently eaten by a mountain lion. The baby chicks from the mother ran around on the dirt floor of the home, bouncing into each other and chirping. The phone rang again and she answered interview questions while preparing some fresh lemonade, made with water from the well. After the call, we asked her who the journalist was. “Someone from BBC, London,” she replied nonchalantly.

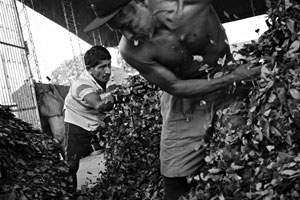

The next morning we bushwhacked through the thick forest behind the house to Zurita’s coca fields. The main pathway was flooded, so we hacked through swampy areas, pushing through vines and clouds of hovering insects. After a couple of miles, the shaded forest opened up to a wide expanse full of coca plants in sunlight. This was their crop. After packing a golf ball-sized wad of coca in their cheeks, Zurita and her husband began spraying pesticides on the coca from plastic packs on their backs. Chewing the coca, they explained, was something they did every day to give them strength while they worked.

When Zurita was done spraying a section of the crops, she sat next to me in the shade, gulped down some water and wiped the sweat from her forehead. She told me about some of the mobilizations she has participated in as a union leader and said that one goal of her work is “to bring the women ahead, by organizing, empowering, orienting them and setting up seminars. Almost ninety percent [of the women in the Chapare] don’t know how to read or write. So, the best school for the women is the union – there we have empowered people. We learn about the law; which laws are in favour of us and which are not. This has all shown us that the union organization is important to defend Mother Earth, defend the coca and defend our natural resources….”

She knows this jungle reality well; yet, there is another life she lives, which occupies her time. It is one of constant travel, union meetings, speeches and interviews with the media. “Sometimes I go for weeks when the only housing I have is in the buses,” she says. “I have to be in one meeting one day and have to travel by night to get to the next one the following day.” In the coca field, this part of her life seems distant. Yet somehow she lives with a foot in both realities. “I produce coca for my children, because if I die tomorrow they will be able to continue to eat thanks to this bit of coca that we produce.”

The Morales Government

Evo Morales, an indigenous coca farmer and congressman with the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) party, won the Bolivian presidential elections in a landslide victory on December 18, 2005. He was the first indigenous president elected in the country’s history, and has proposed to change the government’s policies radically. This May 1, he announced the nationalization of Bolivia’s gas reserves, the second largest in Latin America. The nationalization of the gas was a key demand in protests that had ousted two presidents in two years. The May 1 decree fell short of full expropriation, and many have criticized it for being renegotiation with transnational companies, not full nationalization. However, the MAS continues to enjoy historical backing from the majority of Bolivians. This mandate was enforced during a July 2 election for representatives to the constituent assembly to rewrite the country’s constitution. The constitutional rewrite was another key demand of the social movements that paved the way for Morales’ electoral victory.

Despite some of the administration’s shortcomings, the bulk of the populace and many of the country’s key leftist leaders have given Morales their critical support. Many of them have entered the administration as advisors or representatives to the constituent assembly.

Commenting on the role of women in the new Morales government, Zurita says that the participation of women in the government has not been that large, but this is changing. “Today we have advanced,” she says, referring to the Morales victory. “We can’t expect things to change overnight, but little by little we are moving ahead.”

Zurita was planning on visiting the U.S. in March, 2005, for a three-week speaking tour, which would take her to leading universities across the US. Upon entering the airport to leave for the U.S., she was informed her visa had been revoked due to links to terrorist activity. Many viewed the U.S. move as political intimidation. The Center for International Policy (CIP), a Washington, DC think tank that invited Zurita to speak on this tour, reported that she had been accused of crimes in Bolivia but found innocent in each case: “In Bolivia the word ‘terrorism’ is too often used to brand one’s political opponents. If the terrorism label does not stick – and we strongly believe it does not – the reason for the visa decision must be politics.”

In spite of the U.S. pressure, this human rights and social movement leader continues to work on behalf of her fellow coca farmers. She looks toward the re-writing of the constitution, which takes place in August, as a way to correct the many wrongs that Bolivia has suffered.

This article appeared in the September/October 2006 issue of Canadian Dimension (Good to the Last Drop).