In conversation with Bhaskar Sunkara

The Trump victory and the U.S. Left

Illustration by Max Fleishman

How can we gauge the implications for the American Left of the election of Donald Trump? What dangers does the Trump presidency pose and what opportunities, if any, does it present? To answer these questions, CD spoke with Bhaskar Sunkara, founder, publisher and editor-in-chief of Jacobin magazine. Founded in 2011, Jacobin has established itself as a leading voice of the Left in the Anglo-American world. Sunkara visited Montréal last November to give a public lecture on the challenge of the Trump presidency for the U.S. Left. Andrea Levy had the pleasure of talking with him on behalf of Dimension, which co-sponsored the event with Alternatives and les Nouveaux cahiers du socialisme. We are publishing the first part of the interview here, edited for length and clarity. Part II will appear in our Spring issue.

Canadian Dimension: Clearly, both class and race are central to any complete explanation of what happened on November 8. In analyzing Trump’s victory, some commentators on the Left in the U.S. and elsewhere have emphasized class as an explanatory factor, pointing to the desperation felt by many working class Americans hung out to dry by neoliberalism and the Democratic Party, while others have focused more on race. Looking at how the support for Trump came overwhelmingly from white Americans, cutting across class lines, they see in this election a kind of last hurrah of white supremacy and balk at being invited to understand and sympathize with the white working class at a moment when racialized minorities are being made ever more vulnerable. They feel the left is giving a big swath of Trump voters a pass on bigotry. How do you speak to these tensions?

Bhaskar Sunkara: Well, I don’t split the difference; in general I lie firmly on the side of class in these debates. Obviously race does matter, but I think class is the underlying thing that conditions other oppressions. A lot of discourse has focused on intersectionality, looking at separate systems existing in their own eco- systems and occasionally interacting, whereas I see class as the only free-standing system, without downplaying sexism, racism and the way those interact with class. There is a distinction. I think a lot of recent discussion in the post- election period, and particularly the references to the white working class, for instance, elides the fact that Trump’s base was largely petit-bourgeois. A small business owner would be a typical Trump voter. Also when we speak of the white working class in the context of the election, we are often assigning an identity and coherence that it doesn’t actually have. There were some white workers who voted for Trump and some white workers who voted for Clinton; more unionized white workers would vote for Clinton, while non-unionized white workers would vote for Trump. The vast majority of white workers, like the majority of workers across all races, didn’t vote because they didn’t like either candidate. So I think it makes more sense to talk about white workers than about the white working-class. In a lot of areas, the very same white workers who voted for Trump this time had voted for Obama twice. It’s hard to see that as a manifestation of White Supremacy. I think it reflects the discontent with the state of the country. You have one candidate whose primary selling point was, “I have been in politics for 30 years” — and people don’t like politics, they don’t like the last 30 years, how could that possibly be a good pitch? Even Hilary Clinton’s last campaign slogan in the dying weeks was “love trumps hate.” It’s kind of clever as wordplay but it doesn’t actually express what she was about, what positive things she was going to offer, so it was a very defensive assertion: “I am not Donald Trump; I am not a racist or a sexist.” So I think a lot of people were rejecting that and we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that, besides not voting at all, the next most common choice people made across classes was to vote for Hilary Clinton. The third choice was to vote for Donald Trump. I think it reflects a lot about the Democratic Party, its orientation, how it’s trying to reconfigure its social base, and it shows that years of neglect and not delivering the goods for working class communities across the entire country has come back to haunt them.

CD: But there’s no question that Trump has emboldened elements of the extreme racist right in the United States. There has already been a significant increase in hate crimes.

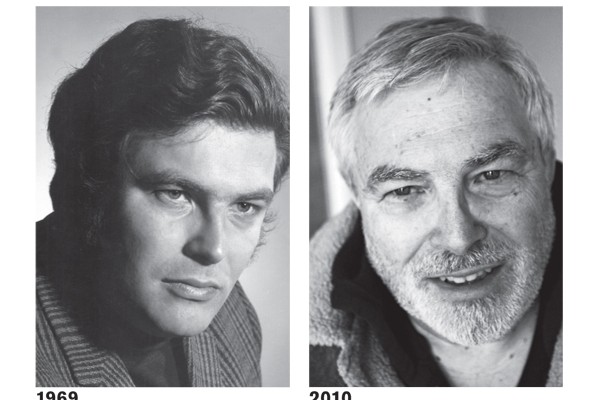

Bhaskar Sunkara

But during this campaign he adopted a xenophobic rhetoric, which is a little different. It was an anti- immigrant rhetoric closer to that of the populist right in Europe, than to the traditional anti-black racism that had animated large chunks of the American right, including elements within the Republican Party. This is an important distinction because I think we should leave open the possibility that if Trump got his way, if he actually pushed through the kind of jobs and infrastructure program that he wants to push through — although the Republican Congress is likely going to be too intelligent to let him do this and cement a coalition behind him — he could I think win a bigger chunk of the black working class.

Steve Bannon, one of the more intelligent of Trump’s far-right aides, says “we can win 30 to 35 per cent of the black vote.” He doesn’t think they can win a majority, but he thinks they can cement that much of a coalition. If you view Trump’s appeal monolithically, as just about racism like a lot of Democrats have, then you don’t understand the reason why 30 to 35 per cent of Latinos voted for Donald Trump, and how he could potentially build this base among black workers. It wouldn’t be a majority base, but it would be enough that, combined with his existing 46 per cent, he would actually have a majority coalition, which right now he does not have. He fluked his way into an election. I’m not downplaying Donald Trump’s bad politics, but this is a little bit different than the traditional American anti-black racism. It is anti-immigrant, Islamophobic, and so on. The question for me is where Donald Trump voters rank xenophobic anti-immigrant sentiment on their list of reasons for choosing Trump. It is my suspicion that they might rank it number four or number five, and we could very easily have the type of politics in the future, a right populist politics, that ranks it number two or number one, which would be very dangerous.

I think right now we are catching it at an early stage. They have power but they don’t have a very firm ideology. They haven’t polarized the country to the right yet. When I look at Donald Trump and then at these far-right elements, I see the threat of a generalized right populist mood as something that may arise in the down the road, rather than something that has already manifested itself.

CD: What do you think is the best strategy now in relation to the Democratic Party? Do you think progressives can or should put their energies into rebuilding and reforming the party or should they concentrate on tapping the mobilization around Bernie Sanders to build an independent progressive political force, perhaps in the form of a labour party? Has the Sanders campaign altered your views on the potential of the Democratic Party in any way?

BS: Right now, I think a lot of our energy should be focused within the Democratic Party, not with a view to reforming it, but basically just to wage a conflict within it. In other words, and I don’t want to sound like a third-period social democrat here, but I think that right now the main enemy is actually the centre within the Democratic Party, not necessarily the right, partly because in the next two months at least, the right is not in power. The Democrats are still in power. Even if you’re concerned about the violence of the state in minority communities, for instance, you’re looking at Democratic mayors and Democratic city councillors. If you’re concerned about deportations, Barack Obama has deported two million people, and he is still president for the next two months. In many ways, I am wary of the kind of sort of popular front “let’s just join hands with the Clintons” vision because I think it will reproduce the same kind of politics that just lost the election, and I fear a scenario where we have politics largely polarized between the establishment centre and a populist right, similar to what you have in, let’s say, France, where the Left is marginalized and reduced to 10 per cent of the vote. I think doing things such as pushing for Keith Ellison as DNC Chair, pushing out Clintonites from the DNC, could serve a useful political role. I don’t think the Democratic Party can be realigned, but I think that the people pursuing that strategy will encounter certain roadblocks or contradictions. Maybe we’ll be wrong and they’ll manage to do what they want. But I think it’s 99.999-per-cent sure that the Democratic Party will not be realigned or changed into a progressive labour party or anything like that, but I don’t think that what they’re doing is necessarily a waste of time. I think they are still mobilizing, they are still pursuing the only avenue that seems to be available. I think a lot of the far left will exclude itself from those efforts but I am wary of staying outside those attempts.

As for the anti-Trump mobilizations, I think that often the problem with these kind of mobilizations is that they are very ephemeral. They basically pop out of nowhere, expressing anger and discontent. There is not much effort to build wider networks and a sustained level of mobilization. I don’t see the necessary potential there. Obviously we need people to come out into the streets as a defensive action once Trump is in power and he pushes through certain things or proposes certain things. At the same time, I do think our main task at the moment is to make it clear that Hilary Clinton and Joe Biden and Barack Obama and the rest of them gave us Donald Trump, so they need to be out of any future coalition, of any future organizing.

One way to think about all this is that for the first time in modern U.S. politics, we actually have a visible Left, a centre and the right — and visible not only in our own minds but visible in the minds of ordinary Americans. So the centre lost to the right in this election and that’s bad for all working people across the country, but the figure of Bernie Sanders, for example, is more popular than either the centre or the right. We’re the least established institutionally, but look at favourability ratings. Not only are there different policy positions, but Sanders’ personal favourability rate is around 60 per cent, compared to Trump and Clinton, whose rate is in the 40s. Notwithstanding the big surge recently for Trump which increased his favourability rate from the 30s to the 40s, he is still well behind that of Sanders.

And the approach to Sanders, which I think makes a lot of sense, is to say, to the extent that Donald Trump wants to do things in the interests of working people, we’ll support him, but anytime he pursues politics that are divisive, sexist, racist, xenophobic, and so on, we will bitterly oppose him. Of course, that’s basically just a ploy to call his bluff. Since there are people in some communities who would have voted for Sanders and instead voted for Trump, because the only choice they were offered on the ballot was between Trump and Clinton, we can’t just immediately take the position that everyone who voted for Trump is a reactionary, and say that we are not going to give him a chance and so on. At least Sanders can’t adopt that rhetoric, and I think Sanders is very well positioned to be an anti-establishment voice while still opposing Trump.

I think that’s the kind of strategy which has the potential to get us to a majoritarian Left politics. I really do think there is a chance. We don’t know who is going to be the vehicle of the struggle, but we do know we have the raw accumulation of forces to have a potentially winning Left populist run at the presidency in 2020. Socialists will have to relate to that critically. I don’t think we should allow our politics to be subsumed in all this, and there will certainly be lots of contradictions and messiness. Under a Clinton presidency — which is again the outcome I would have preferred — we would have had a horizon of 10 to 15 years during which to build up our forces. Now that timeframe has been truncated and the left needs to be ready to run openly Left and openly socialist candidates in 2018, 2020, and pursue a much more visible opposition. I don’t think we are ready for it, but we will have to build the infrastructure as we go.

High schoolers

in Homestead, Fla., protest Trump’s

election. Photo by

Joe Raedle/Getty

Images; posted on theguardian.com Nov. 20, 2016.

CD: Is the mobilization around the Sanders campaign a potential base? Can Bernie hang on to a lot of his support, some of which was alienated when he didn’t get the nomination?

BS: I think Bernie has essentially emerged unscathed. The Clinton centre can’t blame him for them losing to Trump because he did actually campaign for Clinton. Bernie supporters, by and large, supported his decision to endorse the winner of the Democratic primary. Trump voters still saw him as being distinct from Clinton. On all sides, aside from a few far Left fringes, most of whom didn’t really support him to begin with, Bernie’s reputation is intact. I think the real problem is this: I was up in New Hampshire for about a week canvassing for Sanders. I did lots of canvassing in New York. When we get a chance to talk to people in the way we are able to do through a presidential campaign, we find out that people largely agree with us, and despite having had to create a campaign ad hoc, we were still able to win over millions and millions of people; 43 or 44 per cent of the Democratic primary; 23 states. But we don’t have the infrastructure to reach those people outside a presidential election. That’s a real problem.

I think Sanders’ base of voters is still out there and they still agree with us, but we don’t actually have the infrastructure and the means to mobilize them. I think our revolution, and some of the other efforts around the Sanders campaign, isn’t going to amount to much. Our revolution itself is going to be more of a left-wing move on.org plus candidate fundraising. I am also encouraged by certain developments on the far Left: the Democratic Socialists of America went from around five or six thousand members — where it has hovered since Michael Harrington’s days in the 1980s — to around 11 or 12 thousand. So there are vehicles that could develop a larger base, but for now we have the most popular politician in the country, with no means of actually integrating ourselves in the lives of working people. I think we have succeeded in constructing a working class politics but without any rootedness, deep long-term rootedness, in working class communities.

CD: What kind of role is the labour movement playing?

BS: Remember that the majority of the labour movement endorsed Clinton over Sanders. It engages in very short term and transactional politics. I don’t just blame the labour bureaucrats for this. The U.S. labour movement is weak because U.S. capital is strong. It is historically weak because U.S. capital is historically strong. As a result, labour leaders are forced to try to hang on to whatever remnants of strength they have and kind of bunker down and preserve the interests of their membership. They have a lot riding on every contract, like public sector unionism had a lot riding on Clinton winning this election and on certain Supreme Court decisions that might undermine public sector unionism.

To speak to the question you raised before about whether we should we start an independent labour party, I hate to quote Marx to make a somewhat conservative argument, because that is a hallmark of right-wing social democrats all over the world, but I will do just that. Marx wrote that men make their own history but they don’t make it under conditions of their own choosing. I think if it was just as simple as starting our own ballot line, then sure, we would have done it already, but at the level of electoral politics organizing in the U.S. is similar to organizing in a semi-authoritarian state like Singapore or Russia. Say there’s a district with 300,000 people in it and we might need 20,000 signatures to even get on the ballot line. How do we have the resources to get 20,000 signatures? All these things are built to prevent the emergence of a second party.

At the same time, I could register as a Republican almost overnight and the Republican Party has no legal means to expel me unless I go to prison and my voting rights are temporarily revoked while I am in prison. Basically our primary system is facilitated by the State, and the Democratic Party and the Republican Party are not just a ballot line, but that is a good chunk of what they are, combined with a machine and a mechanism for fundraising and for vetting politics and so on. I think the interest in that experiment would be: Can we create an organization that’s dues paying, an organization that is run by its membership, an organization with a set of platforms and a set of priorities, and can we have this organization then run candidates, sometimes on independent ballot lines, sometimes on Democratic ballot lines, in some cities that are dominated by Republicans on Republican ballot lines, and run not just as Democrats or Republicans or Greens or independents, but as Democratic Socialists, or run as what- ever you want to call this formation? I think that could be a short-term path towards building an independent politics without focusing excessively on this idea of creating and maintaining an independent ballot line.

Can Bernie lead us in this direction? No, not necessarily, but he has normalized left-wing politics and even socialist politics for a whole generation of people. Young people are very discontented with both parties, but they like Bernie Sanders, they like those ideas, and they are willing to self-identify as socialists, even if they just basically mean welfare-statist politics. I think that leaves a major opening for our forces. I don’t think we would need many people to get the ball rolling. I think a coherent, unified minority of even 15,000 to 20,000 people can make a major move in this direction. It is kind of splitting the difference between efforts to develop truly independent political action and trying to reform the Democratic Party, but I think it’s worth a try. Obviously all things being different, I would very much like to model a party on a purely independent basis.

CD: So you have in mind something between a movement and a party?

BS: Well yes, I think we need to view them as part of the same thing, like a class movement that has a manifestation in a party with an electoral dimension, but is also active in civil society, all in a general political climate that allows for spontaneous and broad actions under a working class banner. This is nothing new; it’s early German SPD. It’s something the socialists have tried to do for 100-odd years but it’s the only model we have and it’s been pretty successful.

People often talk about anarchist alternatives or horizontal alternatives, and they say that both the Leninist democratic centralist model and the social democratic models have all failed. They really haven’t failed. If you look at the basic demands of the workers’ movement when these parties were set up in the late 19th century, we’ve accomplished quite a lot of those. We’ve conquered — and I say “we” very broadly, of course I come from an anti- Stalinist tradition — we’ve conquered state power across the world with these models. These models have achieved a lot. We haven’t just set up rooftop market gardens or whatever.

CD: But those models are being swept aside to some extent, at least in Europe with the rise of all these new type of Left parties, which are quite different from the standard social-democratic model, and certainly from the Leninist model.

BS: I think the Leninist model is basically dead, or at least what’s understood as the Leninist model. I think any future party will have to be truly demo- cratic centralist, in the broad sense of unity in action. It will have to maintain permanent factions and whatnot. But I think in many ways, the model of parties like Die Linke and Syriza are actually very traditional Left models in the spirit of the early workers’ movement. The only difference is that there isn’t the same level of rootedness. Look at a party like the Italian Communist Party, which got around 30 to 35 per cent of the vote at it peak — and that doesn’t even capture the extent of the PCI’s influence in Italian culture or its visibility and activity within the Italian working class. Compare that to parties like Die Linke, which can get 10 to 15 per cent of the vote even, but don’t actually have a comparable level of strength or rootedness in working class communities. I think that is our main problem. Same thing with the Corbyn phenomenon, we have people pursuing a working-class politics but without that deep working-class base.

There’s basically been a hollowing out, a hollowing out of mass parties and of certain democratic traditions across the advanced capitalist world. This has often been portrayed in very apolitical terms as a crisis of politics or a crisis of democracy, but in fact it’s just the crisis of the Left, because the centre- right parties and a lot of centre-left parties as they have evolved don’t actually need mass politics, only the Left needs mass politics. So Merkel et al can actually govern without any sort of mass mandate or membership or base. But we are seeing some rebuilding. The Labour Party is now up to 600,000 members. That’s completely new. I think it’s basically what we have for now. It is the only model we have. Even Podemos, as it has grown, has developed party structures that are somewhat similar. I think what we have to fight for is extreme internal democracy at these projects at all stages, even if it leads to short-term trouble given the potential for splits and divisions during electoral campaigns and so on. We just have to say that these parties still need to be democratic and they still need to have some sort of accountability from the base to prevent bureaucratization and other distortions.

CD: Pretty well all of the prospective Republican Party candidates were on the far right of the Republican spectrum, so rather than an anomaly, Trump looks to be an expression of a decisive rightward shift in the party. And if we look at the continuing gains of the extreme right in Europe, both west and east, it’s hard not to see neofascism as the spectre haunting the global North today. Is it time for an international popular front uniting the Left across borders and continents in a defensive struggle against this tide of reaction? Is that a realistic ambition?

BS: I think it depends where, but I think in general, no. I think right now we have to attack the centre. We have to be on the offensive and we have to say that the thing fuelling populist right politics in places like the United States and Europe and elsewhere is actually the failure of social democracy in many cases, and in the U.S. the kind of social liberalism associated with the Democratic Party. And we need to offer a positive alternative as a solution. I think if we get caught up in the rhetoric of the anti-fascist struggle of the popular front, we lose sight of that. At this point, given our level of strength, we shouldn’t be associating ourselves with the very discredited elements that people are rebelling against. I think in the United States, we haven’t seen a really massive shift to the right especially if you look at young people. There is really no deep decisive shift to the right. Even anti-immigrant sentiment is still usually expressed by a minority of the population.

Of course, while we are organizing, we should also be organizing defensively in favour of immigrant rights, against deportations, against Islamophobia and so on. But — and this may sound odd a few weeks after Trump’s election — I think in the United States we are in pretty good shape on the Left. I imagine left-of-centre forces dominating American politics in the next five or 10 to 15 years, whereas I think I would be more pessimistic about Eastern Europe and Central Europe, in fact across much of Europe. But the real danger I think is the type of resistance we saw in the face of Berlusconi where people essentially said okay, we are going to line up with the good liberals, the clean government liberals and we are going to have the judges fight these battles for us. It is the kind of mentality that took Rifondazione and put them in the coalition government with the broad centre to try to fight Berlusconi. I see that mentality as really, really disastrous. So in order to defeat the right, I think we need to dislodge the centre.

CD: I find you incredibly sanguine about the Trump election and it’s interesting because of course many people are terrified. When I look not just at Trump but at the people surrounding him — his Christian theocratic vice-president and Bannon and all the other appointments, each of which looks more horrifying than the last — I wonder what the implications are, what amount of damage this administration can do not only in terms of domestic policy but also foreign policy and environmental policy. How do you stay so calm in the face of this?

Obama has deported more immigrants

than any president in American history —

at least 2.5 million

people between 2009 and 2015, including

mothers of U.S.-born

children. The photo

below, which appeared on YouTube, was taken at a demonstration

against deportations

in Washington D.C.,

July 28, 2010.

If Bannon was running the show, it would be terrifying because I think that at least in the short term, they may really build up a real base of support, especially if a lot of these infrastructure programs, and bridges and tunnels were implemented in and around cities, and especially because the black working class, which has been perpetually underemployed under Democratic administrations, might see a short term benefit. Again, it’s not enough to precipitate a massive swing towards the Republicans, but even five or 10 per cent more would be enough to cement Trump’s coalition.

So that’s what keeps me up at night. But I want to add that the Supreme Court certainly matters, and especially when it comes to public sector unions, these decisions will be very bad. Environmentally, I think that, yes, a lot of damage will be done because the little bit of good the U.S. has done trying to reduce carbon emissions has taken place at the executive level by executive measure, so that is all going to go by the wayside. All these things are very bad for the U.S. in the medium and long term, but short term, what can Trump do? I think he can do damage but I think he will be constrained by a few things: for one — and maybe this is my excessively structural vision of things as a Marxist — I think he will be constrained by the markets and I think he will be constrained by his own party. If you look at his first speech after he got elected, he didn’t sound any of his usual xenophobic notes. He didn’t mention building a wall, and so on. He said, “I am going to be a president for all Americans, we are going to have jobs, we are going to unite the country, I am going to do all these kinds of positive things.” I think that’s the danger.

CD: What about reproductive rights?

BS: The real danger is this: Even if Trump wasn’t president, you would see continuing erosion because of the Republican domination of state and local government. It’s not going to be a court decision that does it; I don’t think Roe v. Wade is going to be overturned or anything like that. But right now, if you live in North Dakota, you might have to drive all the way to Minnesota just to get an abortion. This is where the Left needs to fill in. The response should be that we are going to create a left-wing organization, we are going to fundraise and we are going to create an apparatus that will take an approach that’s a little bit different than the focus on lobbying of some liberal reproductive rights organizations, which also need to be defended, especially against defunding. But the Left could actually bring back the old caravans which educate people about where they can go to get abortions and help bring them there for free and protect them on the way there and things like that. The Left can do these things in a politicized manner. But I do think that unless there were to be a swing in the state houses, reproductive rights would continue to be eroded even without Trump.

As for the environment, this is one place where Trump will cause lots of short term harm. We won’t see the manifestation for some years to come. But I think this is one of the problems with the liberal kind of approach under Obama. Obviously they had certain constraints, like not being able to get the votes, but they didn’t mobilize people behind robust climate change legislation. Instead, they pursued a course of trying to fix things from the margin through executive order. So a lot of this is the creation of the Democrats, but I think that, yes, the environment is one place where things are very, very bad. The question is, how do we react and where do we go from here?

Trump won the election, and I really do think that we should at least see the opportunities that have arisen in this moment, and a lot of these new opportunities mean getting rid of the old Democrat Party types that have just cost us the election. Yes, I think there are plenty of reasons to be very, very depressed, but even then, even on the question of environmental politics, we have to find a way to tie in the environment with the popular program. It has to be about telling people, “you don’t have enough and you deserve more.” Because that is the basis of our politics, right? Left-wing politics is about uniting the many against the few and it’s about telling people “you don’t have enough, you deserve more.” “Enough” doesn’t have to refer only to material things. It has to be enough power, enough dignity, enough respect in society, and then, beyond that, we say that there is a group of people, a class of people, preventing you from having more. Now if we try to shoehorn environmental politics into it, and I think we need to, given the threat of climate change, we have to do so in a way that still maintains that basic formula. But instead it’s basically been about pushing the notion that people need to make do with less. I think part of it is trying to build an argument that says “your interests are different than the interests of the people who own coal power plants and who benefit from this fossil economy, and you wouldn’t lose anything by just transitioning to a carbon-neutral economy. In fact, you could stand to benefit.” This hasn’t been clearly explained to people. Even the way Clinton talked to coal communities in Appalachia was very much a zero-sum kind of game: “Yes, there will be some hardship short term,” which is not a message we want to send to people. We will tell them “we will pay you not to work and we will give you jobs with more dignity and so on.” I think the type of environmental politics we’ve had in the U.S. has been very, very bad, and very technocratic. We need a different type of environmental politics.

CD: I understand Trump wants to reaffirm his objective of deporting of at least three or four million illegals. Do you see mass deportations as something practically possible? Would it be some kind of super Migra coming down into neighbourhoods, rounding people up and expelling them? Do you see any self-defence organization arising around that? What can be done to develop that movement and what kind of support can we give it internationally?

BS: I think one thing that’s really scary about this is that Obama has already deported two million people over the course of his terms.

CD: In eight years, right?

BS: Yeah, in eight years. But still if you put it this way, there is going to be a 30 to 40 per cent increase in deportations. These don’t happen in a dramatic door-by-door fashion. It’s much more insidious. For example, someone gets pulled over, doesn’t have documentation and then gets deported, or someone overstays a work visa and then tries to get another job, so they get another work visa but then they’re kind of caught in between. A lot of work needs to be done around this issue. That work already started under the Obama administration, but it needs to be amplified. At this point I don’t want to say there won’t be a massive push for deportation, because there might be. But I suspect it will be more a continuation of the precedents set under Obama. And obviously capital still wants and needs a lot of these workers. Capital is smart enough to know that it is not a zero-sum game, that it is getting a lot of the value from the work these people are doing. So I think what we can expect more realistically is that instead of getting some sort of pathway to citizenship or being told you can pay your back taxes and then you can become a citizen or a permanent resident, there will be some sort of guest worker-type program in which undocumented workers remain in the U.S. under a kind of sub-citizenship regime whereby they are still being exploited for their low wages but are given no way forward; similar to the system in Germany and elsewhere, but worse.

So I think it’s going to be bad, but if it were more dramatic it might be easier for people to immediately mobilize and resist. It’s hard to prognosticate. I think we should prepare for the worst while acknowledging that Obama set a lot of these precedents which means it could happen without really people noticing. People within the Republican Party like Paul Ryan have said that it is insane to imagine that we could deport 10 or 11 million people. It would be the biggest mass deportation in history; it’s not something that’s going to happen, but, then, this common sense capital wing of the Republican Party has lost every single battle over the last year.

CD: Cornel West wrote a piece in The Guardian where he basically says that Trump’s election is the end of neoliberalism and it ended with a neofascist bang. In other words, the neoliberal era has turned into a new configuration of capital that rejects globalization, economic nationalism, promotes racism, etc. Do you think this is true? Are we seeing an adaptation of neoliberalism or an end to neoliberal strategy or a new configuration of capital?

BS: Trump fundamentally agrees with the neoliberal playbook. He wants to renegotiate NAFTA and other trade deals. He basically wants a regime that is very similar the existing order. I don’t think there has been a shift here. He is capturing some of the anger people feel for neoliberalism but he is redirecting it towards a different sort of neoliberal program. So I think there is real continuity here. One thing to keep in mind though is that Donald Trump’s base — and this was true of the Tea Party too — had broken with neoliberalism in a certain undefined right-wing way. The Tea Party was a bunch of lunatics empowered by the Republican base to serve a certain objective but it has taken on a life of its own. Here’s one really interesting thing about Donald Trump. I think that as Marxists we have continually underestimated the political agency of, for lack of a better word, the petit bourgeoisie. Every single major segment of capital was with Hilary Clinton. Every single major segment of labour and progressive groups was with Hilary Clinton. Yet still Hilary Clinton lost and I think that tells us something about the power and agency of this particular group. But no, I don’t think there has been a fundamental break in any direction. I think it’s just the ugliest, worst face of the same neoliberal order. That does hold out some hope because Trump is going to disappoint and anger a lot of people, and we have to keep fostering that discontent. That is one reason why we don’t write off Trump voters, because if you want to build a really, really angry base of people who are truly outraged about Trump, not now, but three years from now, it will be the people who are okay with him now and willing to give him a shot. Because a lot of the rest of us are going to burn ourselves out in the next two or three years in opposition. But I really do believe there are a lot of people who are going to become pissed off and fed up with him: 60 per cent of the people who voted for him don’t actually think he is fit to be president, which is, I think, a good thing.

To be continued in our next issue.

This article appeared in the Winter 2017 issue of Canadian Dimension (Short Change).