Canada should extricate itself from the F-35 and more

The federal government must not just cancel the F-35 purchase but fundamentally rethink its role in the US military enterprise

An F-35 Lightning II test aircraft with the Canadian flag, along with those of other industrial participants, painted on it. Photo by Julianne Showalter/US Air Force/Wikimedia Commons.

Prime Minister Mark Carney’s call for a review of the deal to purchase F-35 fighter jets has thrust the aircraft back into the public debate. Announced in January 2023, the decision to purchase 88 F-35 planes was costed at $19 billion; Canada is so far only committed to purchasing 16 planes. Thanks to statements by Donald Trump about annexing and subjugating Canada, public opinion in Canada about the United States has declined significantly, and over 30,000 Canadians have signed a petition to cancel the F-35 deal. Given this public mood, and Carney’s recent recognition that “the old relationship… with the United States… is over,” the government should not just cancel the F-35 purchases but fundamentally rethink its role in the US military enterprise. As Yves Engler argued recently in Canadian Dimension, it “makes little sense to remain integrated with the military of a hostile country whose president wants to annex Canada.” But will it happen?

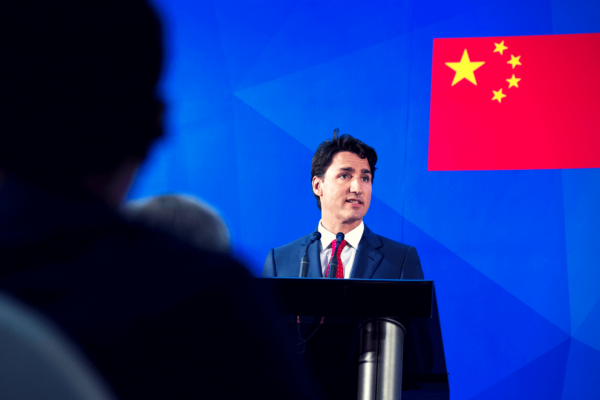

We’ve been here before. Ten years ago, during his election campaign, Justin Trudeau vowed to scrap the unpopular F-35 program and launch an open competition. Months after he became prime minister, the government committed $45 million in 2016 to stay in the deal. This was on top of earlier investments of $10 million in 1997 and $100 million in 2002.

Former Prime Minister Stephen Harper had already committed Canada to buying 65 F-35 planes. The timing of the decision was striking. Just one month earlier, the US government had begun reviewing its own commitment because the cost of each plane exceeded the original estimate by 84.8 percent, breaching the 1983 Nunn-McCurdy Act, which is “designed to curtail cost growth in American weapons procurement programs.”

The following year, the Parliamentary Budget Officer found that purchasing and operating 65 F-35s would cost $29.3 billion, rather than the $16-18 billion reported in the media. In 2012, the Auditor General reported that the military had concealed the real cost figures when recommending the plane. The Conservative government eventually froze additional purchases “until further due diligence, oversight and transparency is applied.”

The cost escalation has only continued. From 2001 to 2022, the price of each F-35 plane has jumped from USD$69 million to USD$131.3 million. All this money for a plane likely to be incompatible with Canadian technology and missions. A more recent concern has been over the US’s ability to limit Canadian control over the plane because Washington will retain the ability to carry out upgrades and software improvements necessary to keep the F-35 up and running.

In the past, politicians have countered financial or operational arguments against purchasing the F-35 by promising lots of jobs—and this strategy has worked.

For example, Harper extolled the “huge economic benefits for all of Canada’s aerospace industry” and the many Canadian companies with “development contracts.” Likewise, when the Liberal government announced the $19 billion deal in January 2023, Defence Minister Anita Anand boasted that “every [F-35] will also include Canadian components” and that about 3,300 jobs would be added to the Canadian economy.

Elements of the same script have been adopted by Carney, who is talking about benefits from the F-35 deal to “Canadian workers and the economy” on the campaign trail. And, no surprise, Lockheed Martin, the company that builds the F-35, has offered to create more jobs in Canada if the country sticks with the original commitment.

Falling for this argument would be a mistake. First, given Trump’s America-first rhetoric, he will likely demand that Lockheed Martin move these jobs to the US. Second, and more important, many studies have shown that investments in military production produce fewer jobs than spending the same amount on other sectors of the economy, for example, renewable energy, health care, and education. Increasing military expenditure will result in the diversion of funds from socially productive purposes and create more unemployment.

At the same time, if Canada accepts a key role in manufacturing the F-35, it is automatically implicated in US military actions. Such complicity has been unpopular within Canada, which is why a majority opposed involvement in US-led wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

This is not about just complicity with US empire, but also with the actions of other F-35 customers. Israel has been using these warplanes to bomb and kill tens of thousands of civilians in Gaza and Lebanon. Recently, the Israeli military announced on social media how they used a “Beast Mode” feature in the F-35 to conduct strikes. Such public advertising financially benefits Lockheed Martin, and perhaps even its Canadian contractors, but comes at the expense of humanity.

Canadians have an opportunity in this election to demand that politicians sincerely commit to divesting from American imperial warfare. Rather than fixating on the merits and demerits of the F-35 and jobs, they should question Canada’s alignment with the US in military and foreign policy priorities, and press political parties to affirm their commitment to international law and human rights—and demand they follow through.

Janani Rangarajan is a policy analyst at the University of British Columbia’s Sustainability Hub. Lydia Mikhail is a final year student at the University of British Columbia majoring in Economics and Political Science. M.V. Ramana is the Simons Chair in Disarmament, Global and Human Security and professor at the School of Public Policy and Global Affairs, University of British Columbia. He is the author of, most recently, Nuclear is not the Solution: The Folly of Atomic Power in the Age of Climate Change (Verso, 2024).