Afterlife of the Meng Wanzhou affair

Part one in an eight part series investigating the crisis in Canada-China relations

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau delivers opening remarks at a business event with the Chinese Entrepreneur Club in Beijing, August 30, 2016. Photo courtesy the Prime Minister’s Office.

Amid the wreckage of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the United States and its allies have turned their sights on China. University of Victoria professor emeritus and historian John Price examines the rise of the coalition of Anglo settler colonial states of Canada, the United Kingdom, the US, Australia, and New Zealand, and how they are today fomenting conflict in the Asia Pacific. You can read the series in its entirety here.

On Friday, September 24, 2021, two jets passed each other over the North Pacific. Aboard one was Huawei’s Chief Financial Officer, Meng Wanzhou; two Canadians, Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, were on the other. Their flights crossed paths after the three were released following almost three years in detention—Meng, held in Canada while processing an extradition request from the Trump administration, and the two Canadians, apprehended on charges of spying.

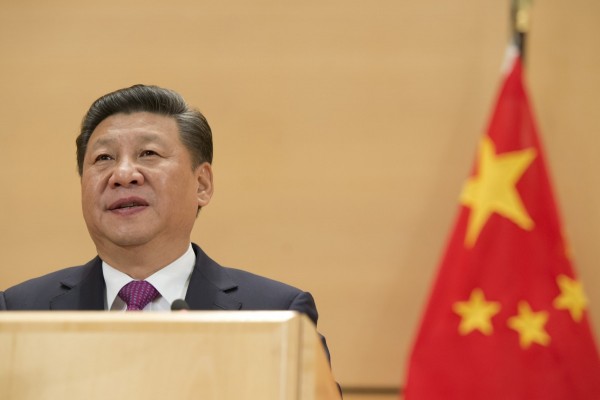

The exchange came after current US President Joe Biden and China’s President Xi Jinping struck a deal to exchange the detainees in an apparent attempt to rid themselves of an unnecessary nuisance in an increasingly hostile confrontation.

The end of the Meng-Spavor-Kovrig affair has not improved Canada-China or US-China relations. Even as the exchange was taking shape, the Biden administration announced new measures that now include:

- the signing of AUKUS (Australia/UK/US), a trilateral military pact for Australia to build nuclear-powered submarines to deploy against China. The deal caused a furor as it involved Australia tearing up a multi-billion-dollar contract with France;

- reinforcing the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (the Quad), a militarized alliance that includes the US, Australia, India, and Japan to confront China in the Asia Pacific;

- the CIA establishing a new “China Mission Center” to take on what the agency’s director, William Burns, described as “the most important geopolitical threat we face in the 21st Century, an increasing adversarial Chinese government.”

A Nanos poll conducted after the end of the hostage affair suggests that Canadian public opinion regarding Huawei and China has become increasingly antagonistic. The poll, commissioned by the Globe and Mail to reinforce its criticism of China, demonstrates a growing hostility to the country among Canadians. Similarly, the European Council on Foreign Relations released poll results from twelve member states suggesting that 62 percent of respondents believed “a new cold war was taking place between the US and China.”

No wonder, then, that shortly after the release of Meng et al., Canadian Senator Yuen Pau Woo became a target of racism for his views on the Meng-Spavor-Kovrig affair, according to a recent Canadian Press article. Citing former US ambassador Chas Freeman that the “US, assisted by Canada, took Meng hostage in the first place as part of its trade and technology war with China,” Woo was chastised by Chris Alexander, a former Canadian diplomat and immigration minister. “By claiming Meng was ‘taken hostage’ @yuenpauwoo has violated his oath as a Canadian senator and should resign,” Alexander tweeted. “Mouthpieces for foreign propaganda… should have no place in Canada’s Parliament,” he continued.

Even though Woo was quoting an American of European descent, his use of the term “hostage”—mildly challenging the carefully constructed image of Canada as a liberal state—provoked howls of conservative rage. This episode highlights how dangerous it can still be for Asian Canadians and Asian Americans to publicly intervene on issues related to China.

By claiming Meng was ‘taken hostage’ by Canada, @yuenpauwoo has violated his oath as a Canadian Senator & should resign.

— Chris Alexander (@calxandr) September 26, 2021

Mouthpieces for foreign propaganda, including those backed by China’s United Front Work Department, should have no place in Canada’s parliament. https://t.co/XVWyIDgpbA

Anti-Asian racism and Sinophobia

Images and reports of racist attacks on those who are racialized as “Asian” highlight the violent nature of many of the incidents. But the racism extends into many if not all facets of life, to the point where 58 percent of Asian Canadians polled in May 2021 reported having experiences of discrimination over the past year.[1] The racist attacks sparked a surge in organized resistance on the part of Asian communities in Canada, the United States and around the world, at the same time as the Black Lives Matter movement arose as a transnational phenomenon.

Activists organized locally (Project 1907 and www.elimin8hate.org) and nationally across Canada, coalescing in the National Forum on Anti-Asian Racism held in May 2021 and a follow-up event in November.[2] In both Canada and the United States, academics of Chinese origin have felt particularly targeted and are calling out programs that essentially engage in racial profiling, focusing on those with ties to mainland China.[3]

The anti-racist movement was amplified as Black and Indigenous communities rose up to expose deeply-rooted anti-Indigenous and anti-Black discrimination embedded within social structures in both Canada and the United States. This movement sparked public reviews of healthcare systems in both British Columbia and Québec, with the NDP government in the former proposing new anti-racism laws and disaggregated data collection that would expose race-based discrimination.[4]

As highlighted by the recent publication, Challenging Racist “British Columbia”: 150 Years and Counting, anti-Asian racism draws on the deep well of white supremacy and settler colonialism that persists in the form of systemic racism today. This, however, does not explain the upsurge in racism at this specific time—the contingency of racism. As Senator Woo puts it, “there has been a deafening silence on the key question: What explains the recent rise in anti-Asian racism?”

For Woo, the current racist upsurge is related to recent discourses blaming foreigners (code for “Chinese”) for single-handedly sparking the rise in real estate prices and money-laundering. Theses half-truths, he believes, nurtured a “racist demon in our community that was unleashed when COVID-19 struck.” Carleton University professor Xiaobei Chen makes explicit that the demon is Sinophobia (fear or contempt for China, its peoples including those of Chinese heritage outside China, or its culture). It promotes a politics of fear associated with the rise of China as an economic power, stimulating racial anxieties that are channeled into ideological arguments including conspiracy theories regarding the origins of COVID-19, worries about Chinese corporate takeovers, or the presence of “agents of influence” for Beijing in Canada.[5]

Too often, one-sided journalist accounts related to these issues reinforce current forms of Sinophobia and can be found on the shelves of public libraries everywhere in Canada.[6] This demonization of China directly impacts Chinese Canadian communities in complicated ways, with many fearful of being branded an agent of China if they speak out.

Nevertheless, the anti-racist movements in Canada and the US disrupted the campaign to demonize China and those of Asian heritage to some extent. Additionally, two cataclysms shook Canada in mid-2021, diverting attention from Canada-China relations. In May, the Tk’emlups te Secwépemc First Nation in Kamloops confirmed that the 215 unmarked graves found using ground-penetrating radar were likely children who died at the Kamloops Indian Residential School. Long known to exist by Indigenous communities, the continuing revelations nevertheless shocked the country as people came face-to-face with the truth about residential schools and Canada’s ongoing legacy of settler colonialism. This was followed by an unprecedented heat dome a few months later, jacking the temperature in Lytton, BC to 49.6 degrees Celsius (121.3 Fahrenheit)—the highest temperature ever recorded in Canada. The following day, a wildfire burned the village to the ground, killing two people and ushering in the worst fire season on record with hundreds of heat-related deaths. The climate crisis had struck with a vengeance.

Highlighting Canada’s own record as a settler colony and the severity of the climate emergency, these moments acted as counterweights to the campaigns of anti-Asian racism and Sinophobia, and indirectly suggested the need for a global effort that includes China to fight climate change.

However, the Trudeau government seems determined to ignore the implications of its own status as a settler colonial state and the exigencies of the climate emergency. Instead, it has announced it will support the “diplomatic boycott” of the Beijing Winter Olympics in support of the Biden administration’s anti-China policies. A government decision to ban Huawei from high-speed telecommunications in Canada appears imminent and will bring Canada into line with the coalition of Anglo settler colonial states (the US, the UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand) that sponsors the “Five Eyes” spy network. This network has been the spear-carrier in the anti-China campaign, enabling and spreading Sinophobia, and increasing the dangers of war in the Pacific.

Part 2: Huawei and the US ‘pivot to Asia’

John Price is professor emeritus at the University of Victoria, author of Orienting Canada, and a member of the Advisory Board of the newly formed Canada-China Focus, a project of the Canadian Foreign Policy Institute and the Centre for Global Studies (University of Victoria).

[1] UBC, The National Forum on Anti-Asian Racism: Final Report (UBC, October 2021), 13, accessed December 11, 2021.

[2] UBC, The National Forum on Anti-Asian Racism: Final Report. For insights into the state of anti-racism, see the source provided.

[3] Steven Chase, “Academics of Chinese Origin Warn New National Security Screening for Research Funding Could Lead to ‘Racial Profiling’,” Globe and Mail, August 2, 2021; Jeffrey Mervis, “China Initiative Spawns Distrust – and Activism,” Science, V. 374 N6568 (November 2021): 673.

[4] M.E. Turpel-Lafond (Aki-Kwe), In Plain Sight: Addressing Indigenous-specific Racism and Discrimination in B.C. Health Care (Vancouver: 2020). For the report on the BC investigation, see the source provided.

[5] Zhipeng Gao, “Sinophobia during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Identity, Belonging, and International Politics,” Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, (September 2021); Lok Siu and Claire Chun, “Yellow Peril and Techno-Orientalism in the Time of COVID-19,” Journal of Asian American Studies (October 2020): 421-440; Nyland, Forbes-Mewett, and Thomson, Sinophobia as Corporate Tactic and the Response of Host Communities, Journal of Contemporary Asia, 41-4 (2011): 610-631. For detailed analyses of conflations associated with Sinophobia, see the sources provided.

[6] Journalistic works such as Nests of Spies, Claws of the Panda, Wilful Blindness and more recently China Unbound all contribute to Sinophobia.