Progressive nationalism and the fight for Canadian sovereignty

Canada’s dependent relationship with the US has been a major foreign influence and a fundamental constraint on social progress

Labour unions and social movements are pushing for a third wave of progressive nationalism, rooted in Canada’s post-war history, as a response to US trade aggression and corporate integration. Photo courtesy Unifor.

As the first session of Canada’s 45th Parliament is set to open in mid-September, there is a growing clamor for Mark Carney’s Liberal government to come out fighting in the trade and investment war with the United States.

From Ontario Premier Doug Ford to a group of 70 cultural and academic leaders including former Governor General Adrienne Clarkson and author Margaret Atwood urging Carney to defend the country’s “digital sovereignty” and protect privacy from overreach of the government’s Strong Borders Act, the message is the same: toughen up and stop appeasing the Americans.

The sternest language came from the labour movement. “I wasn’t happy,” Unifor National President Lana Payne told her union’s national convention in the last week of August about Carney’s decision to revoke Canada’s retaliatory counter tariffs on a range of American products. Payne reminded Carney he was elected “on the promise of a fight back and a defence of critical sectors… That was not only strategic it is what we expect of you—you don’t win by conceding.”

Payne went further and slammed corporate Canada’s “appeasement” policies to get any deal possible with the US. “Governments don’t have the plan we need to protect Canadian jobs and defend cored industries—not yet. We need a bold vision: a true, multi-sector, job-creating, made-in-Canada industrial strategy.”

In contrast, business and Western Conservative premiers welcomed Carney’s step-downs on the digital services tax and the countervailing tariffs. After 40 years of deep integration with the US on every front from trade to economic policy, foreign affairs, defence, technology and culture, appeasement from the top of the business class could be expected. Goldy Hyder, president and CEO of the Business Council of Canada, spelled it out. “How are we going to review and renew the USMCA?” Hyder asked, arguing that “find[ing] a way forward” in its negotiations with the US is more important for Canada than the tariffs.

Veterans of the anti-free trade movement are not surprised either by the desperate attempt to salvage the special relationship with the US. Maude Barlow, past chairperson of the Council of Canadians and a leader in the anti-free trade and -globalization movement has seen it before:

There are of course differences between then and now, the most important being that our political elites were driving the earlier integrations as hard as they could, where today, the Carney government has been elected on the promise that it will delink us from depending on the US economy as rapidly as it can. What connects these contexts is the ongoing reality that the corporate lobbies in Canada did not have Canada’s interest at heart during the free trade fight and still do not. The big business community in Canada worked with its counterpart in the US to lead the campaign for free trade and, unsatisfied with their ‘wins’ in that deal, tried, unsuccessfully, to further deep integration with their 2005 Security and Prosperity Partnership for North America.

For Carney’s government, the Liberal Party, and for Canadian labour and social movements, “elbows up” is a rendezvous with a defining feature of Canadian political economy. From John Diefenbaker to Pierre Trudeau and Brian Mulroney, Canadian independence and national policy have been central to the character and potential of Canada. Canada’s dependent relationship with the US after the Second World War has been a constant and pervasive foreign influence and constraint on social progress. As such, it has also been a fulcrum of Canadian politics and policy recognized by a long analytical tradition across the progressive spectrum, from red Tories to the socialist left, leading distinct waves of progressive nationalism that shaped Canada’s social movements.

With some important exceptions, labour and the Canadian left in 2025 are late to the analysis and action. While Canadians spontaneously rallied behind the elbows up movement, boycotting US goods and travel, there have been only a few visible initiatives. Unifor’s Protect Canadian Jobs campaign, including several thousand attendees at a rally in Windsor in April, has been the most prominent labour campaign. Former NDP MP Charlie Angus’s Elbows Up Resistance Tour has brought out thousands to community meetings. Angus, former Privy Council Clerk Alex Himelfarb, former MP and Osgoode Hall Law School scholar Craig Scott and Council of Canadians Chairperson John Cartwright initiated the “Pledge for Canada” that secured over 75,000 endorsements in March and April.

By way of contrast, back in 1970, a coalition of progressive leaders and intellectuals quickly collected 170,000 individual endorsements of the founding statement of principles of the Committee for an Independent Canada. The CIC was the centrepiece of the first wave of progressive Canadian nationalism after the war, uniting a large swath of the centre-left and splitting the governing Liberal Party. In the 1960s and 70s Canadian independence was closely related to opposition to US wars, growing US ownership of the Canadian economy and also reflected in the Canadian union movement opposing US domination of Canada’s labour movement.

It is noteworthy that the manifesto for post-war Canadian nationalism, George Grant’s Lament for a Nation, was a plea for conservatism. By 1965, Grant had already concluded that US domination over Canada precluded his vision of progressive conservatism, writing, “the good society was one in which government restrained selfishness and fostered a greater concern for the common good.”

A year later, Lester Pearson’s finance minister, Walter Gordon, published a short book that became a blockbuster in Canadian affairs. In A Choice for Canada, he argued:

We still have a choice. We can do the things necessary to regain control of our economy and thus maintain our independence. Or we can acquiesce in becoming a colonial dependency of the United States, with no future except the hope of eventual absorption.

Gordon soon left politics and went on to found the CIC with Abraham Rotstein, Peter C. Newman, George Grant and Kari Levitt, among others, but not before he convinced then Prime Minister Lester Pearson to appoint a Task Force on Foreign Ownership and the Structure of Canadian Investment, chaired by economist Mel Watkins. The 1968 Watkins Report became a cornerstone for national economic policy.

In 1969, Watkins and James Laxer blew the doors open on left-wing nationalism with the manifesto of the Waffle group in the NDP (of which Cy Gonick, the founder of Canadian Dimension, was a key member). An explicitly socialist statement, the Waffle made it clear that Canadian independence was a programmatic necessity:

The major threat to Canadian survival today is American control of the Canadian economy. The major issue of our times is not national unity but national survival, and the fundamental threat is external, not internal.

American corporate capitalism is the dominant factor shaping Canadian society. In Canada, American economic control operates throughout the formidable medium of the multi-national corporation. The Canadian corporate elite has opted for a junior partnership with these American enterprises. Canada has been reduced to a resource base and consumer market within the American Empire.

Capitalism must be replaced by socialism, by national planning of investment and by the public ownership of the means of production in the interests of the Canadian people as a whole. Canadian nationalism is a relevant force on which to build to the extent that it is anti-imperialist. On the road to socialism, such aspirations for independence must be taken into account. For to pursue independence seriously is to make visible the necessity of socialism in Canada.

The first-wave nationalists did not succeed in breaking Canada out of the American empire, but the Foreign Investment Review Act (1973), Canadian content regulations for Radio and Television (1970/1971), PetroCanada (1975) and the National Energy Program (1980), among other national policies, were reflections of the Canadian progressive nationalist agenda.

The sovereignty election of 1988, fought over Canada-US free trade, underscored the centrality of the US relationship in Canadian development and fundamentally altered the economic and political direction of Canada. It also catalyzed a second wave of progressive Canadian nationalism with a stronger class and geo-political analysis.

Maude Barlow, Bob White, Tony Clarke, and other leaders of the anti-free trade movement described free trade agreements as part of the architecture of global capitalism, undermining the sovereign rights of nations to shape their own future. In the words of Bob White, from a 1988 speech to the United Fishermen and Allied Workers Union:

This agreement is about more than the removal of some tariffs. It is about the control and use of our natural wealth, the control over the investment that shapes our industrial structure, and the ability to use popular pressure to influence the direction of the economy and how its benefits are distributed. The free trade debate is, therefore, not just about how we see Canada today, but about differing visions of what we hope to do about Canada’s future.

By 2024 the prophecies of three generations of progressive Canadian nationalists were largely fulfilled. While the US proportion of direct foreign investment diminished with economic globalization, Canada’s dependence on the US market had grown from 60 percent in the early 1980s to a peak of 87 percent at the turn of the century, before receding somewhat. Notably, 100 percent of natural gas exports and 95.7 percent percent of crude oil was shipped to the US in 2024 and the value of the Canadian dollar had become tied to oil prices.

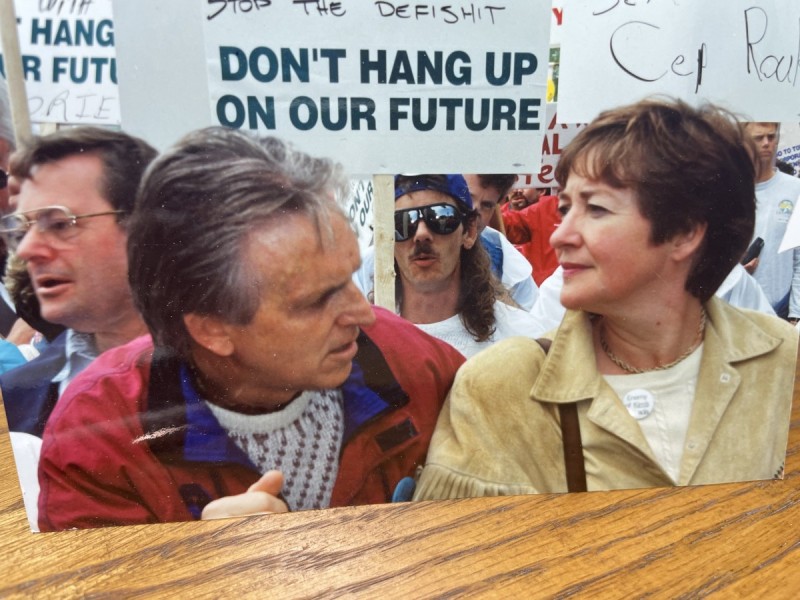

Canadian Auto Workers President Bob White and Maude Barlow in 1988.

Arguably the larger impact of integration policy was cultural and political. Major Canadian national instruments—PetroCanada, Air Canada, CN Rail—were privatized in the 1980s and 90s, as were key provincial telecom and energy utilities. Industrial planning and direct investment was largely abandoned, and Canadian jurisdictions acted like the boy scouts of free trade, disavowing Canadian procurement policies even while the US pursued Buy-American policies. The CBC was significantly defunded while the media landscape shifted dramatically to digital platforms and newspaper circulation declined. It was not until 2023 that Canada took the first tentative steps to tax the US streamers dominating Canadian communications and entertainment (although Carney recently abandoned those in trade war negotiations).

The updated free trade agreement that replaced NAFTA, the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement, or CUSMA, restored some measure of sovereignty with the abolishment of investor-state dispute settlements, as well as NAFTA’s energy proportionality clause with the US—but it was too little, too late. When Trump declared that unilateral tariffs against key Canadian export industries would leave Canada unviable and a target for annexation, there were palpable fears that this was a serious, existential threat.

The threat to Canadian sovereignty is real and it demands a renewed analysis and a third wave of progressive nationalism to meet the challenges of the post-globalization era of authoritarian US imperialism. The fight for Canada is the central political issue of our time and it will inevitably unite or divide Canadian labour and social movements.

Some view Canada’s new, ‘elbows up’ nationalism through a partisan lens and see it primarily benefiting pro-corporate Liberals. Their priority is the protection and advancement of social programs and climate policy and they are justifiably critical of the very mixed record and corporate orientation of Liberal governments. There is a warranted sharpening of criticism of the Carney government, legitimate questioning of the national projects agenda and warnings of corporate capture. But progressive and left nationalism has always brought strong criticism of governments and corporate agendas to the forefront in support of national policy and an independent Canada.

Canadian independence will require a countervailing economic and social policy to the business agenda, and like Canada’s entire post-war history, meaningful social and economic progress will require finally breaking free of US empire.

Maude Barlow sees the elbows up movement as aligned with the values and priorities of the earlier waves of the Canadian independence movements:

I can assure people that when we launched the fight against the Reagan-Mulroney free trade agreement, we were not narrow nationalists and had nothing in common with the right-wing populism of today. We were profoundly opposed to deepening our ties—politically and economically—with a right-wing regime whose social and foreign policies we abhorred. We were deeply worried that we would lose our social security systems and be forced to follow foreign wars meant to cement American hegemony. A very important feature of our struggle was cultural; Canadian writers, filmmakers, visual artists and journalists were at the foreground against that free trade deal, demanding the right to tell our own stories.

The previous waves of progressive nationalism were based outside of party politics in popular movements and bold platforms for social advancements, and each are urgent at this moment. The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives is leading a coalition of Canadian organizations towards that kind of platform at an “Elbows Up Economic Summit” in Ottawa on the eve of the new Parliamentary session.

“The overarching challenge is building an economy that is truly sovereign and self-reliant, and not get sidetracked by longstanding corporate ultimatums for tax cuts, deregulation, and pipelines,” economist Jim Stanford said in announcing the summit and releasing a “fact book” benchmarking 15 key economic indicators for Canada in the trade war.

“The time has come to stop waiting for Washington to determine our future,” Unifor Director of Research Angelo DiCaro told the union convention in August. “What Canada needs now is to imagine a future beyond the current crisis.” The Unifor policy he outlined featured industrial policies covering 14 economic sectors, and seven strategic programmatic objectives. At the centre of those, “Enabling Canadian Ownership and Control,” declares that:

Strategic assets such as vital infrastructure, the broadcast and digital realm, and critical natural resources, should remain in Canadian hands. Government must empower domestic firms, workers, and communities to shape the future of our economy. Unifor will pursue a strategy of Canadian government as well as First Nations, Metis and Inuit peoples, ownership, control and democratic management of critical national industries, programs and resources.

The Canadian business class won the free trade battle in 1988, but in 2025 they were rebuffed when Canadians elected the Carney government on a mandate to defend sovereignty, protect workers in Trump’s trade war, and begin breaking free from economic dependence on the United States. Labour is now pressing the government to deliver on that mandate, organizing protests, building political influence, and advancing a credible social and industrial strategy. Corporate Canada, however, has very different objectives, seeking placation with Trump, including a weakened CUSMA, and the complete adoption of the business agenda that is hardly different from 1973 or 1998.

To shift the balance, it will take the full force of a new, third wave of progressive nationalism—one strong enough to back labour’s demands and move Canada toward true independence and meaningful social progress.

“We cannot be complacent,” Maude Barlow forewarns. “In building this ‘new Canada,’ we must be vigilant that we don’t mimic the worst of what we are trying to leave behind.”

Fred Wilson writes on labour and social issues. He is retired from Unifor and is the author of A New Kind of Union (Lorimer, 2019). He also volunteers as an advisor to the Mexico Worker Rights Action (CALIS) project. Follow his posts on Bluesky and Medium.