Settler colonialism: What’s in a name?

A critical look at a framework that has reshaped the study of Indigenous-settler relations

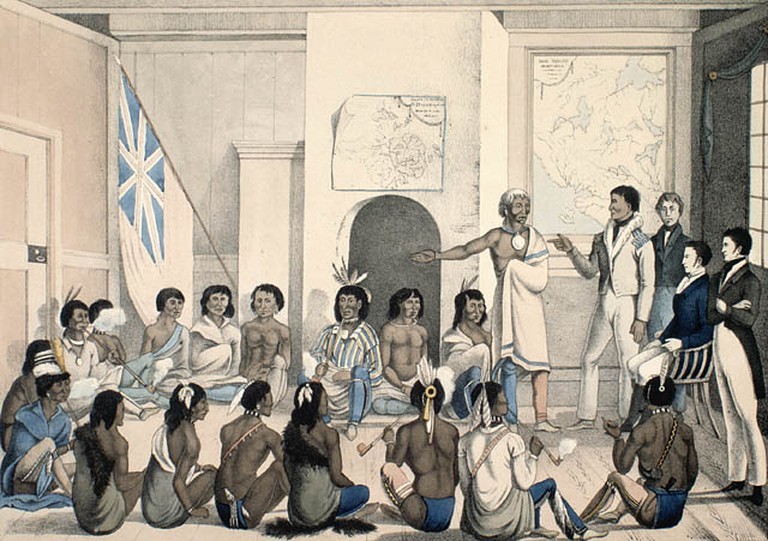

Red Lake Chief makes a speech to the governor of Red River at Fort Douglas in 1825. Fort Douglas was the first fort associated with the Hudson’s Bay Company near the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers in today’s city of Winnipeg. Painting by Peter Rindisbacher. Image courtesy Library and Archives Canada.

The term settler colonialism, used barely at all decades ago, now anchors progressive discourse. Indeed, not to use this designation to describe specific nation states—past and present—will undoubtedly raise eyebrows in certain circles. Some who adopt the terminology have seldom paused to reflect seriously on its salience through time (is there a periodization that captures the nature, date of arrival, and changing momentum of settler colonialism?) or its applicability to vast, complex, and unevenly developed places. The theoretical edifice, originally constructed by an English historian transplanted to Australia, Patrick Wolfe, and championed by Lorenzo Veracini and the journal he founded in 2011, Settler Colonial Studies, has come to have an amazing purchase on radical sensibilities.

Canada is now something of a poster-child for the settler colonial framework. Outside of an entrenched and increasingly bellicose right-wing milieu, settler colonialism is largely unquestioned as an apt appellation for Canada. The northern reaches of the Western Hemisphere, within which Canada developed, was premised on competing empires’ risible imperial assumptions that territories inhabited by those Europeans considered “barbarians” and “sauvages” were terra nullius—”land belonging to no one”—and subject to a “doctrine of discovery” that received sanctimonious religious rationale. Early Catholic papal bulls declared that as the so-called Age of Discovery unfolded, emissaries of feudalistic absolutist states possessed the God-given right to “capture, vanquish and subdue the saracens, pagans, and other enemies of Christ,” entitled to seize “all their possessions and properties,” and subject supposedly uncivilized peoples to “perpetual slavery.” As a nation state christened in Confederation, Canada consolidated on dispossessed Indigenous lands. Rooted in colonialism, the new Dominion, Great Britain’s “richest colony,” rested on the pillars of capitalism: privatized property and the profit accruing from it. If slavery, ultimately, was not to be the lot of “pagan” peoples, dispossession, marginalization, coerced assimilation, cultural annihilation, and even, at times, genocide, certainly were.

What settler colonialism as a conceptual framework has done is not without merit, and is undeniably noteworthy. It has in its confident proclamation that all citizens in the settler colonial state have a responsibility to address the devastating, long-lasting, and ongoing impact of colonialism, demanded that a history of almost unfathomable, and often deadly, hurt and humiliation be repudiated and transcended. In placing the accent on settler responsibility for colonial depredations, and calling attention to the role that ordinary Canadians play in excusing, and even fomenting, the violence of Indigenous dispossession, marginalization, and worse, settler colonialism as a conception of history is a challenging orientation. It calls out complacency, pressures refusals and repudiations of past wrongs, and encourages popular resistance to ongoing oppression.

The insistence that settler colonialism is a distinctive vehicle of oppression and subordination necessarily forces the majority of Canadians to confront conventional erasures, which remain largely unacknowledged. For the making of the Canadian nation state entailed costs, terrible and traumatic, ruinously imposed upon First Nations, Métis, and Inuit men, women, and children, as well, of course, on many, many others. Seeing those costs clearly, and addressing them frontally, is mandatory if a new kind of just Canada is to be built. That Canada cannot be erected on the craven idolatries of colonialism and capitalism, money and its powers. It will need a new imaginary, one that relentlessly refuses possessive individualism’s worship of accumulation (which always entails destruction), privatized property (which always excludes the majority from the ‘holdings’ of the minority), and profit (which is necessarily extracted from the labour and resources of the dispossessed, be they Indigenous or non-Indigenous).

What settler colonialism gives with its righteous and reasonable hand of demand, it may well take away on other fronts. As a trans-historical, essentialized conceptualization, settler colonialism has not been particularly adroit in its appreciation of colonialism’s nature. This changed through time; it operated differently in dissimilar contexts and environments. How colonialism scratched itself into specific territories (such as, for instance, the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence lowlands, the Pacific Northwest, or the subarctic and Arctic north) in highly uneven ways was always synchronized with capital’s shifting gears and the rise of capitalist state power as the overarching structure of governance. Capital and the state reconfigured the material settings in which colonialism co-existed with and contributed to the profit system’s capacity to impose its principles and power as the commonsensical ideological foundation of society.

Colonialism, and its relationship to Indigenous peoples, took on different trappings through time and space. Indigenous political economies and ecological embeddedness varied, and so too did colonialism’s reach into them, its influence and impact registering in a variety of ways that nonetheless shared certain foundational features. There were, to be sure, many continuities in colonialism’s historical development, but that discernible sameness must also be set against obvious modifications, even transformations. In the clash of feudal empires in the contested lands of the misnamed “New World” in the centuries reaching from 1500-1760 Indigenous peoples were often crucial allies of specific imperial interests. Their territories and entitlements inevitably received some perfunctory recognition. Reinforcing this reciprocity, however uneven, were the exchange relations of the fur trade (whose history developed differently throughout Canada’s regions, from east to west, south to north), premised as they were on Indigenous lands, waterways, and other resources. First Nations, Métis, and Inuit knowledge and productive capacity were essential as long as fur orchestrated exchange relations and commerce.

This material reality was being undermined as British North America and its contests with an emerging United States in the late-18th century shifted the geopolitical context in the years leading up to the War of 1812. That was perhaps the last war fought on the continent in which Indigenous warriors and their alliance with the colonizing Crown harkened back to earlier relations of relative (but always unequal) reciprocity. By the time Canada consolidated in the Confederation era, socio-economic relations had changed. Factory production, railways, and immigrant populations came to the fore, integrated into evolving agriculture, small-scale craft productions, an emerging manufacturing system, and a developing market society. Indigenous peoples, increasingly looked upon differently, were no longer perceived as valuable allies and necessary producers of fur trade profit. They had become irksome throwbacks to a way of life displaced by a new political economy, one ordered by the cash nexus. A colonial mindset could conceive of Indigenous peoples only as wards of a now powerful (and ruthless) domestic state. Reduced to objects of governance through policies of coercive assimilation, First Nations were subject to the codified colonialism of the Indian Act of 1876. One-sided treaties legalized the theft of Indigenous lands, the reserve system evolved into “prisons of grass,” and the cultural genocide of the residential school system left thousands of Indigenous children marooned between two ways of life, one of which the state and church-run schools did their utmost to obliterate, the other refusing them welcome and entry.

Painting by John Richard Coke Smyth. Image courtesy Canadian Historical Prints and Watercolours Collection/Library and Archives Canada/Flickr.

As resilient as Indigenous peoples were, many suffered throughout the 20th century, but numbers of them managed to mount mobilizations of resistance. By the 1970s, these campaigns of refusal twisted the state’s coercive assimilation arm and pushed this adversary to abandon policies of subordination centuries in the making. The result was a liberal rhetoric of recognition of indigeneity and entitlement that demanded gestures, too often decidedly empty, of reconciliation. This shift in the outward proclamations of the colonial state at least opened out toward the possibility of change as the modern Canadian nation state entered the 21st century. How settlers factored into this complicated and constantly moving colonial history inevitably entailed an array of responses. This was especially evident as capital and the state exercised impacts in the 19th and 20th centuries that differed substantially from the earlier trajectory of European-Indigenous contact in the era of competing empires and the commerce in animal pelts. Settler colonialism, as an interpretive framework, understates the extent to which capital and the state set the stage on which settlers acted. It homogenizes the experience of colonialism, stripping it of the capacity to address the differences in power exercised by settlers, the state, and those whose socio-economic superiority was decisive, measured in the vast influence their ownership of so much insured.

Cui bono? Quis determinat? As the capitalist state consolidated and Indigenous peoples were displaced in the forward march of Confederation’s railways and western settlement in the post-1870 National Policy years, who benefitted more from the routing of the Métis-led War of Resistance in the mid-1880s and the starvation-induced displacement of Indigenous bands? Is the burden of benefit usefully foisted on to the shoulders of the impoverished homesteader eking out a living near Brandon? Or does it more substantially lie with the Canadian Pacific Railroad and the corporate moguls backing John A. Macdonald and the rising Canadian state? This is not to say, of course, that the majority of settlers, whose claims to small property were a significant component of their self-conceptions and capacities to sustain themselves, did not gain in the capitalist economy’s divvying up of spoils and privilege. Yet who (or what) actually pulled the strings of power, determining the negotiation of treaties and orchestrating the displacement of Indigenous peoples? Who conceived of, constructed, and implemented the policies ordering Indigenous displacement and dispossession, and sustained residential schools, constraining through brutal coercions generations of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit youngsters?

As the Cree professor and poet, Solomon Ratt, himself a residential school survivor, writes in one of his two contributions to a new edited collection of essays, On Settler Colonialism in Canada: Lands and Peoples: “Imagine;/you are a child playing about,/jumping, climbing trees,/marveling at everything in the world,/secure in the love you feel from others/…then the priests came to kidnap.” Are the priests merely settlers? Or are they something else again, doing their version of God’s work with the blessings of the higher authority of organized religion, so often a vanguard of colonialism and a structure of oppression that would later be shored up by the material sanction of a powerful state and its capitalist architects? In the ledger of gain recording status, wealth, and power among all Canadians, most non-Indigenous peoples ranked far below the small number of those who constituted the country’s ruling elite.

Settlers, however much they have to atone for, took a backseat to capital and the state in both determining the course of colonialism and setting the tone of Canadian society, in which racism found fertile ground in the soil of everyday life. To be sure, settlers were often malicious proponents of white supremacy, their conscious acts and human agency striking out at the Indigenous “other,” squatting on lands not theirs, utilizing violence and vitriol to suppress and steal, and typecasting First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples. But without the many winks and nods, if not active encouragement, of capital and the state, settlers in Canada would not have seen themselves possessed of the license to engage in aggressions and acts of suppression which, it must also be recognized, were never the entirety of Indigenous-white relations. Too much of the settler colonialist writing homogenizes this history of differential power. Capital and the state loom large and structure much of what was possible for workers, small farmers, and immigrants to do and come to grips with. The conceptual framework of settler colonialism too often simply sidesteps basic questions—cui bono and quis determinat, “who benefits” and “who decides”—so crucial to a historical materialist analysis of Canadian society. Settler colonialism as a framework of understanding Canadian history and the country’s current conjuncture forces important recognitions and admission of much that has been ill-considered or denied, but it also obscures some fundamental features of this necessary accounting.

All of this was on my mind as I read the essays comprising the useful collection put together by David MacDonald and Emily Grafton, a book that will take its place on the expanding library shelf of Canadian settler colonial studies. On Settler Colonialism contains 18 distinct chapter-length articles and two poems, as well as an introduction by the editors. These individual components appear in four parts, ordered by concerns with violence and genocide, logics of empire, relating and reckoning in settler colonial society, and Indigenous knowledge.

This quadripartite organization may well have been necessary, although it often seems arbitrary. The subjects of the essays invariably bleed into one another, an indication of the layered complications that will arise in any serious engagement with settler colonialism. Essays on Black and Indigenous solidarity within the settler colonial experience by Malissa Bryan and Angie Wong’s account of the archive of Chinese women’s writing and how it evolved in light of living in Canada, yet was grounded in lives beyond the nation’s borders, are placed within a section on genocide and violence. This is understandable. Yet these essays might fit equally well alongside some of the discussions on relating and reckoning, which contain explorations of Canada’s differentiated population and how specific groups fit into a settler colonial mosaic. This latter component of the book includes Jérôme Melançon’s consideration of francophone communities, minority settings, and the always troubled issue of bilingualism in Canada; Desmond McAllister’s reflections on growing up as a mixed-race person in Saskatchewan; and Bernie Farber’s and Len Rudner’s meditation about Jewish experience and its relevance to addressing settler colonialism, how it has been constructed, and what it entails.

Chris Lindren’s and Michelle Stewart’s account of racialized policing and the death of Lindren’s brother, Neil Stonechild, explores the commonplace terror inflicted on Indigenous peoples by the armed force of the state. Stonechild, a 17-year-old Saulteaux First Nation youth, was in police custody on a cold Saskatoon November night (the temperature approached -28 degrees Celsius) in 1990. His frozen body, subsequently found in a field, was clad in only a light jacket, jeans, and a solitary shoe. Bruising on the young man’s wrists indicated Neil wore the bracelets of police confinement: handcuffs. An initial inquiry quickly closed the file on Stonechild’s death prematurely, holding no one responsible. This Saskatoon Police Service ‘investigation,’ later judged “superficial and totally inadequate,” was revisited, in good part because of protests by Lindren and others. A 2004 Saskatchewan government Commission of Inquiry into Stonechild’s death determined that two police constables were the last to see Neil alive. Even after years passed, the available evidence suggested that the cops undoubtedly transported a confined Stonechild to the outskirts of town and, at best (the worst involved more violence), abandoned him to make his way back to warmth and sustenance. This was a commonplace police practice on the prairies, part of the structure of terror that Patrick Wolfe associates with settler colonialism, the event euphemistically referred to as the “Starlight Tour.” Lindren and Stewart admonish settlers to take Neil Stonechild’s death to heart, to read their account “slowly and with intention,” checking their “privilege” and becoming “unsettled.”

The introduction to On Settler Colonialism closes with MacDonald, “an Indo-Trinidadian and Scottish settler-academic,” and Grafton, a “Métis Nation” member, declaring that they hope the book “offers thought-provoking, innovative, and diverse reflections on the history and current state of Indigenous-settler relations in settler colonial Canada.” The history conveyed in this volume, while often alluded to, is however largely without appreciation of the complexities I sketched above. More of the essays concentrate on the modern period, addressing the post-Second World War years that coincide with most of the authors’ life experiences (by my admittedly arbitrary count, the vast bulk of the contributors–perhaps as many as 14 out of 18, as well as the editors’ introduction–address a more contemporary history of the Canadian settler colonial state). A number of the contributions to On Settler Colonialism engage with the complicated reality of how oppressed minorities confront settler colonialism. How empire refracted racialized experience within the varied diasporas that constructed a melding or divergence of cultures within settler colonialism figures forcefully in a number of essays. Indeed, this shaking up of settler colonialism through interrogating the complicated mix of Canada’s immigrant-fed demographic makeup is a unique contribution of this collection.

Another focus of the publication is an exploration of how Canadian institutions and constitutional traditions align with settler colonialism and undermine Indigenous human rights and entitlements. These discussions include Rebecca Major’s harrowing exposure of how Canadian agencies, services, and policies in the health sphere reproduce longstanding discriminatory practices, particularly as they affect women’s reproductive care and wellbeing. Two essays on constitutional order and indigeneity by Métis authors Paul Simard Smith and Emily Grafton allude to milestones in the making of settler colonial Canada. To be sure, historical appreciation of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the critique of governance delivered by Louis Riel during his 1885 trial, where the leader of the recently-routed War of Resistance pilloried the “sham representation” afforded peoples of the North-West, is evident. For the most part, however, the contributions to On Settler Colonialism pass over the historicized making of settler colonialism rather lightly, understandably so given the preponderance of social science authors among the book’s contributors.

Battle of Batoche during the North-West Rebellion, published by Grip Printing & Publishing Co., Toronto. Image courtesy Library and Archives Canada/Wikimedia Commons.

Essayists do include historians, but two of these tend to sidestep the actual historical structuring of settler colonialism in their approach to present issues. Historian Karen R. Duhamel focuses on the normalization of gendered violence as evidenced in the liberal state’s post-2015 reluctant declaration of a crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA+ People. In a wide-ranging, albeit brief, account of Asian indentured labour and the British Empire, Ajay Parasram explores his own background with a concern of how best to “reuse the table scrap offered by official Canadian multiculturalism.” In the double diaspora that took South Asian peoples to Caribbean plantations and then to Canada, Parasram discerns a “necessary therapy for intergenerational colonial healing in [a] post-British still-colony,” a communing with ancestors that draws guidance from varied struggles to “embrace the obligations of decolonization.” In contrast, the historian James Daschuk does address an historical moment in settler colonialism, and a crucial one at that. Daschuk takes a close and detailed look at the state execution of eight Indigenous men, condemned to the gallows for their part in the mid-1880s War of Resistance led by Riel. His treatment of “The Battleford Hangings and the Rise of the Settler Colonial State” is illuminating on many levels, but Daschuk perhaps too easily conveys a sense of settler colonialism, not as a process and deep structure, but as a distinct event. Colonialism’s rise within the territory now known as Canada no doubt intensified with the suppression of the Métis-led insurgency of 1884-1885. Nonetheless, it had been around for centuries. Events of 1885, as significant as Daschuk shows them to be, were part of a much longer continuum.

That continuum is the substance of perhaps the most wide-ranging, intriguing, and venturesome essay in On Settler Colonialism, Peter Kulchyski’s “A Contribution to Periodizing Settler Colonial History in Canada.” Kulchyski, a committed and creative Indigenous studies scholar (and former Canadian Dimension editorial board member), does what few others in this collection attempt, historicizing and conceptualizing settler colonialism as an interpretive paradigm.

Kulchyski’s periodization of settler colonialism is both theoretically sweeping—drawing on writers as diverse as Wolfe and Veracini, Karl Marx and Frantz Fanon, Jean-Paul Sartre and Harold Innis—and historically situated. He develops the “global features and historical pacing of settler colonialism” to offer “a new periodization as a key tool,” but one that is humble in its understandings of the complexities that intrude on the past and present of settler colonialism. If Kulchyski’s periodization is ordered along material fractures of the economic and the political (“capitalist totalization” and the entrenchment of governance in a powerful state), he is mindful of the extent to which a rich history of Indigenous resistance animated shifts in these deep structures of determination, contesting “the repressive regime and the exclusion of Indigeneity from the national self-representation.”

Roughly stated, Kulchyski’s periodization suggests major transformations in settler colonialism in the 1500-1869, 1870-1951, and 1951 to the present years. In the first phase of settler colonialism, the economics of the fur trade orchestrated colonialism and commercial capital until the nation-building of Confederation and the National Policy ushered in an epoch of political subordination. This political colonialism was achieved first (1870-1951) in the repression of coerced assimilation and then, in subsequent years (1951 to the present) in “ideological mechanisms of social control.” Kulchyski’s insights of change through time are crucial. They provide discerning perceptions that explain history’s layered differentiations. Too often, settler colonialism’s homogenizing tendency to elide remarkably dissimilar experiences bypasses such historical changes. These nonetheless took place within colonialism and under the weight and influence of capital’s growing power and authority, which conditioned the evolution of the state. That process of state formation was accompanied, of course, by changing policies, increasingly orchestrated by bureaucratic officialdoms and hegemonic assumptions.

Kulchyski’s theoretically poised periodization thus warrants serious reflection by all of those interested in settler colonialism. This considerable achievement, however, is perhaps less convincing precisely because Kulchyski does not allow himself to question settler colonialism as a theoretical framework explaining Canadian history and calling forth a specific kind of political response. Who, on the left, does in the current political climate?

One problem with this lack of critical engagement with the conceptual edifice of settler colonialism is Kulchyski’s easy assimilation of a complex history to this paradigm. Who exactly were the settlers so decisive in the “elimination of the native” that Patrick Wolfe has dubbed critical to the settler colonial imperative? The fur trade that Kulchyski rightly sees as economically so important in the 1500-1869 years could hardly have been sustained for centuries were settlers an effective means of eliminating Indigenous peoples or obliterating their lifeways and traditions. But with white settlements scattered few and far between, often regarded by the powers that be (the Hudson’s Bay Company and an early colonial officialdom) as an irksome thorn in their side, colonialism’s initial capacity to suppress First Nations and Inuit communities was somewhat circumscribed. The very existence of the Métis Nation could be construed as a means of eliminating the native, and this has been suggested by certain settler colonial theorists, such as Wolfe, who include “officially encouraged miscegenation” among those developments contributing to the “logic of elimination.” Fur trade company officials acknowledged the value to them of marital alliances among Indigenous women and fur trade voyageurs, other contracted labourers, and even clerks and the occasional chief factor. The Métis offspring of these fur trade unions continued to work in the industry for generations. To be sure, the children of these “officially encouraged” marriages experienced a range of treatment from their fathers of European origin, running the gamut from loving recognition to cruel abandonment. Nonetheless, a Métis Nation in Canada did emerge, and it can hardly be considered a component of any logic of the elimination of the native. Métis peoples themselves would probably respond that this is a rather one-sided view, an interpretation that hardly does justice to their unique political economy, culture, and history of resistance against colonialism.

Kulchyski’s claim that the first, centuries-long period “when relations between Indigenous peoples and emerging settler colonial subjects were motivated primarily by economic concerns (from about 1500 to 1870)” also strikes me as a tad one-dimensional. It bypasses too easily, for instance, the significance of military alliances among First Nations and competing empires and the significance of political recognitions of Indigenous peoples that clashing European absolutist states were forced to concede, even in the cauldron of mercantilism and commercial competition. Evidence of this is abundant, and surfaces in the ways in which Indigenous warriors were regarded by the British Empire during the War of 1812 as valued military allies. This contrasts sharply with how the Colonial Office of that same empire wanted no part of “savage” indigeneity being drawn into the suppression of the anti-colonial rebellions of 1837-38. Something quite significant changed in the politics of Indigenous-colonial relations in those brief decades, structured as they were by developments material and ideological, and pointing toward transitions of considerable import.

Kulchyski’s periodization also tends to present writing by major historical figures, such as Karl Marx, in line with settler colonialism’s theoretical presentation of historical development. Kulchyski suggests that major contributors to the settler colonial paradigm have “tied” their understandings of this concept to “the Marxist concept of primitive accumulation, which refers to a process of separating people from the land in order to use the land to generate capital and to transform land-based people into dispossessed workers.” Assertions such as this skate on some thin interpretive ice. Wolfe and Veracini, for instance, clearly differentiate their writing from that of Marx and his perspective on primitive accumulation.

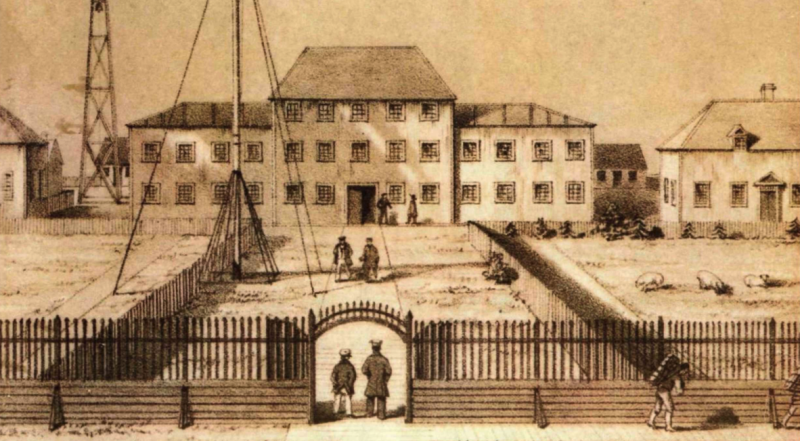

Coloured lithograph showing the Hudson’s Bay company headquarters at York Factory, Manitoba in 1853. Image courtesy Library and Archives Canada/Wikimedia Commons.

There is another problem of assimilation in Kulchyski’s settler colonialist periodization: virtually any and all writing is presented as congruent with this conceptual framework. Theorists such as Patrick Wolfe and Lorenzo Veracini, according to Kulchyski, “have tied” their notion of settler colonialism to “the Marxist concept of primitive accumulation, which refers to a process of separating people from the land in order to use land to generate capital and to transform land-based people into dispossessed workers.” I suppose many interpretive hairs might be split over the meaning of “tied” in such a formulation, but my reading of most settler colonial theorists is that they have less liking for Marx’s understanding (or a very convincing sense that they understand its nuances) than Kulchyski implies. Veracini is adamant, for instance, that “colonial and settler colonial forms should not only be seen as separate, but also construed as antithetical.” Wolfe has taken pains to differentiate his viewpoint from earlier theoretical formulations by Marx and Rosa Luxemburg, who premised their understanding of capitalist development and colonial depredation on the workings of primitive accumulation. Wolfe asserts that his formulation of “preaccumulation” is crucially different than “the European experience of primitive accumulation that has figured so prominently in Marxist historiography.”

There is, in much settler colonial literature, a tendency—refuted by John Bellamy Foster, Brett Clark, and Hannah Holleman in an important Monthly Review article—to espouse a rather dogmatic view that typecasts Marxism’s conceptualization of primitive accumulation. In this reading, primitive accumulation is a stage in historical development rather than an ongoing process, an event-like phenomenon that, whatever its protracted character, must inevitably be discounted because it presents the Indigenous confrontation with settler colonialism as a finished, completed historical happening. In this understanding of settler colonialism, perhaps too much of a hard and fast separation of dispossession (conceived only in terms of land) and exploitation (the extraction of surplus at the point of production) is drawn. Too often, the expropriation of land that made capitalist production possible and the separation of producers from their means of subsistence are depicted as consecutive rather than intertwined moments of a single historical process. As Kulchyski aptly describes in his notion of “capitalist totalization”—the reshaping of space, time, subjectivity, knowledge, and language—dispossession and proletarianization have always been linked. Both are original and ongoing features of capitalism, particularly in settler colonial contexts where Indigenous peoples have not only been dispossessed of their lands but also incorporated into wage labour systems. In this sense, dispossession and exploitation are not distinct mechanisms but parts of the same process of capitalist expansion.

Other writers’ analytic wagons are also hitched to the settler colonial horse, which drives relentlessly forward. Thus Kulchyski describes Hugh Brody’s The People’s Land: Inuit, Whites and the Eastern Arctic (1975) as “an early and very nuanced description of settler colonial social dynamics in contemporary Inuit communities.” Kulchyski does not say that Brody’s book, written more than a decade before discussion of settler colonialism was placed on the analytic agenda, is confirmation of settler colonialism, but neither does he suggest that it is not.

As I read Brody’s book, however, it complicates and even separates itself from many of the conventional wisdoms of the settler colonialist framework. It looks at settlements in the Arctic, to be sure, and Brody does not understate the racist typecasting and apartheid-like conditions that were commonplace during his lengthy stays in Arctic communities. Yet in The People’s Land there is a dialectical relationship of white settlers and the Inuit in which the clash of a hunting people, “seen as an embodiment of nature, as part of the land, beyond the reach of culture” and colonizing “civilization” is a complicated relationship. According to how I read Brody, this dynamic reached far beyond the subordinations and settler colonial ‘exterminism’ that structures so much recent writing. This is not to suggest that Brody excuses whites in Arctic settlements, or understates Inuit resentment and resistance. But in the end, Brody grasps, I believe, that it is the capitalist state and the pushing of the industrial capitalist frontier into the Arctic that constitute the potent threat to the people of the land. Over the course of 1970-73 expenditures on oil and gas exploration in regions of the Arctic rose from $34 million to $230 million, and by 1972 over 425,000,000 acres in the Northwest Territories were covered by leases secured by the energy corporations and other capitalist interests.

Brody concludes that whites living in the Arctic may well be “agents of colonialism,” but many of them are nonetheless aware “of the difficulties many Eskimos” confront. It is the state and capital that push those difficulties and that orchestrate white settler agency in the north:

As the industrial frontier pushes deeper and deeper into the Eskimos’ world, so the difficulties are compounded: the possibility of a mixed economy decreases, while the knowledge, skills, and ways of life most eastern Eskimos prefer, are directly threatened.

…the future of Eskimos, Eskimo society, and Canada’s role in the north will be determined by agreements and relationships between a powerful government and a tiny minority of the nation’s population.

This strikes me as less about settler colonialism and more about capitalism and colonialism.

Few passages in the lexicon of settler colonialism are cited more than Patrick Wolfe’s categorical claim that, “Settler colonies were (are) premised on the elimination of native societies… The colonizers came to stay—invasion is a structure not an event.” Or, in another iteration: “the exploitation of native labour was subordinate to the primary object of territorial acquisition. Settler colonists went to stay.” To be sure, some of this factors into Brody’s The People’s Land. It is nonetheless difficult to engage with this nuanced treatment of whites and the eastern Arctic, their relations unfolding at the interface of capitalism and colonialism, and not see complexities aplenty that complicate, even run against the interpretive grain of, the settler colonial framework.

Some random passages from Brody illuminate this convoluted character of settler-Indigenous relations, never seamlessly severed from the materiality of class formation:

Many Whites do seek to identify themselves at some level with the ‘savage,’ a desire that is revealed in their enthusiasm for the land, their keen interest in the history of Arctic exploration and in accounts of the explorers’ first encounters with truly traditional peoples. And this interest does conflict with their desire to improve ‘savage’ customs.

The ‘savage’ is seen (at least in White fancy) only in the older men who, they believe, are still essentially Eskimo; when talking of them, the Whites seem to regret much of what they do and express, albeit implicitly, quite strongly anti-colonial views. The same views are revealed by Whites who lament the whole process of change and modernization in the Arctic, for they are horrified at the replacement of the ‘savage’ by the ‘bum’, of the proud and independent hunter by the down-and-out labourer.

The Eskimo is, therefore, an embodiment of nature and in many respects a surrogate for it. He receives from the Whites a curious blend of approval and revulsion—approval because he has triumphed over nature (thereby achieving the essentially human), but revulsion because he is still part of nature (thereby remaining less than human).

Eskimos in settlements who live in government-built houses with subsidized rents and southern services, who are under the direction of southern political institutions and southern officials… must try, somehow, to stand against and perhaps rise above the flood of White influences the settlement brings them, even though the ground they stand on is forever shifting.

Colonists express colonialism in many different ways. They like to offer ‘solutions’ to ‘problems’… Some advance the notion of aboriginal poverty: the natives were—and perhaps still are—savage, heathen, and therefore impoverished. The solution to that problem is ‘civilization’. Some are concerned with giving natives qualifications, and want to train them for some form of labour. Others focus on the poverty and distress that contact with outsiders has created and therefore advocate various welfare measures. Others again note a poverty of the spirit and argue that the solution lies in a return to ‘traditional’ values and practices, and they will, if necessary, teach the natives to be natives.

Ultimately, Brody’s compelling account suggests that a ‘new’ traditional Inuit way of life has emerged, based on a mixed economy, in which hunting coexists with trading and waged jobs. Those Inuit who have “year-round employment” continue to return to the land to pursue game, even as “wage labour is now the mainstay of economic life in the settlements.” Brody’s attention to class, a subject settler colonial theory too often handles with either silence or scapegoating, is illuminating: “White hostility towards the Eskimo is better understood as the result of inter-class oppositions than as the living disappointment in their failure to realize infantile images.” Rather than confirm the existence of settler colonialism in the eastern Arctic, Brody’s The People’s Land opens out into an interrogation of the claims of this interpretive framework.

Hamlet of Arctic Bay, Nunavut. Photo by Mike Beauregard/Wikimedia Commons.

The analytic issues flagged above are, of course, debatable. I do not raise them to repudiate the entirety of the settler colonial interpretive agenda; rather I want to place some question marks around its all-too-easy embrace. Nor have I subjected Kulchyski’s essay to serious—and some will say unnecessarily close—scrutiny because it is a weak contribution to this volume. On the contrary, it is precisely because it is one of the most penetrating and substantial contributions to this collection that it merits critical and careful examination. Unlike many of its companion essays in On Settler Colonialism, Kulchyski’s chapter rests on deep conceptualization and a refusal to separate out the histories of Canadian colonialism and capitalism.

One of the other contributions to this book that also assumes this close and reciprocal relationship—capitalism and colonialism—is Joyce Green’s scathing reminder that settlers who venture on to the terrain of interpreting the experience of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit men, women, and children must do so with caution and respect. Like Kulchyski and Brody, Green grasps that, “Corporate interests, not adventure, saving souls, or philanthropy, is what always motivates colonialism.” It has been that way since the mercantilist Hudson’s Bay Company first received its charter in 1670, indeed from well before that. Like Kulchyski and Brody as well, Green accents the crucial importance of land, which she sees as in some ways too cavalierly handled in the willingness of so many to offer empty and perhaps ill-conceived land acknowledgement statements and gestures. Green, a member of the Ktunaxa Nation whose territory once encompassed parts of present-day British Columbia, Alberta, Montana, Washington, and Idaho is a feminist political scientist who has produced decisively important work on gendered Indigenous politics, among other topics. In her hard-hitting contribution to this collection, she offers a blunt warning to whites who do not know what they are doing when they venture onto the material, analytic, socio-economic and cultural terrain of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples.

In suggesting that settler colonialism, as an approach to Canadian history, has both educated us and prodded non-Indigenous peoples to take seriously the record of colonialism and its ravages, I have tried to be cognizant of the responsibilities Green insists all settlers must shoulder, as well as the need to proceed with respect. But in the current moment it is perhaps easy to fall short of such intentions.

My message is simple, and it is in part a response to the pushes and prods that settler colonialism has directed at non-Indigenous peoples within societies such as Canada. What I believe absolutely crucial in the current moment, when the political tables have been turned so forcefully against what remains of the left, is the necessity of rebuilding the organizations and fighting capacities of political opposition. Central to this project will be the creation of coalitions and campaigns of the dispossessed—all of the dispossessed. This is vital if colonialism and its twin, capitalism, are to be transcended, displaced by an alternative socio-economic order. If such a better world is to be in birth, it will be one premised not on privatized property, profit, and the subordination of the many, but on collectivity and a just and equitable alternative to the profit system that rules modern Canadian society.

The conceptual cornerstones of an interpretive edifice such as settler colonialism offer us useful pressures. Taken in its entirety, however, the settler colonial framework too easily homogenizes power as the prerogative of all non-Indigenous peoples and can be critiqued for understating the role of decisive determinants. Decades ago, one of the most important Indigenous scholars and activists to emerge out of the Red Power movement of the 1960s, Howard Adams, noted that when aggrieved First Nations warriors cast their lot with the Métis-led War of Resistance against colonialism (and its capitalist engines and institutions) in the mid-1880s, they took an insurrectionary stand in particular ways. Their violence was directed, legitimately so, against “those white men who held them in subjugation, and not against white people in general.”

What’s in a name? Quite a bit. Perhaps as we move forward and mobilize in these threatening times, we might consider building broadly and focusing on the general structures that have done the vast majority of the dispossessed—however differentiated in their degree of oppression and exploitation—so much damage. Colonialism and capitalism, as the deep structures generating our discontents, can of course be modified by adjectives, meaningfully enhanced by qualifiers. Many of these qualifiers are and will prove to be politically as well as intellectually significant and relevant. Yet, resistance and refusal, if they are to succeed in winning a truly mass base, might well begin with consideration of those proper, and determinative, nouns—capitalism and colonialism—without sacrificing accountings of the debts and obligations we all share.

Bryan D. Palmer is an historian of labour and the left. His most recent books are a trilogy addressing the history of capitalism and colonialism in Canada, two volumes of which have appeared, while one is forthcoming: Colonialism and Capitalism: Canada’s Origins, 1500-1890 (Lorimer, 2024); Capitalism and Colonialism: The Making of Modern Canada, 1890-1960 (Lorimer, 2025); and Capitalism, Colonialism, and Crises: The Remaking of Canada, 1960-2025 (Lorimer, forthcoming).