Indian Horse is a film all Canadians must see

Indian Horse, a film based on the late Richard Wagamese’s bestselling novel, opens in theatres nationwide on April 13th. Wagamese was a masterful storyteller as well as a long-time columnist for Canadian Dimension; however, people (especially settler Canadians) should gather to watch and witness the film for another reason.

At a time of rampant anti-Indigenous racism and growing residential school denial, the big-budget film confronts the legacy of Indian Residential Schools in Canada and does so in a relatable way for a general audience: the story is rooted in the main character’s relationship with the game of hockey. For anyone interested in hockey and history and figuring out how to strengthen relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, Indian Horse is a must-see movie.

The film is set in 1950s Ontario where Saul Indian Horse, a young Anishinaabe boy, is disconnected from the land, ripped from his family, and placed in St. Jerome’s Catholic residential school. School officials prohibit the use of Indigenous languages and generally treat the children poorly. One of the students even chooses to commit suicide over continuing to endure her school sentence.

Saul chooses a different path. He seeks salvation in the game of hockey. Father Gaston Leboutilier takes a liking to the young boy and allows him to watch Hockey Night in Canada. The teacher even grants Saul access to St. Jerome’s ice rink in the early mornings where he learns to skate and shoot and stickhandle the puck. Despite his enthusiasm for the game, he is still deemed by the school’s staff to be too young to join the St. Jerome’s organized hockey team. Saul nevertheless persists and proves to be a keen student of the game.

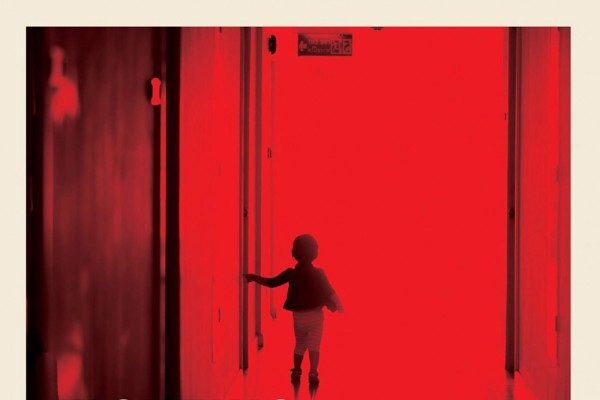

Still from the film, courtesy of Elevation Pictures

When a player is injured during a game, Saul is thrust into action and he takes advantage of the opportunity to display his skill. Saul is simply sensational. Hockey becomes his escape, literally and figuratively. With the support of Father Leboutilier, Saul is recruited to leave the school to play on a local team and live with a supportive Indigenous foster family. He jumps at the chance.

After impressing in the local league, Saul’s talent is noticed by a scout and he is offered a spot on the Toronto Monarch’s professional team. The scout tells Saul that if he can hold his own in the minor league, he is sure to get a call up to NHL. Saul’s professional hockey career proves to be difficult, however.

White players target him with aggressive checks and bigoted remarks, and he is frequently taunted by racist fans threatened by an “Indian” with skills that could rival the game’s best White players. When Saul scores, which he does often, fans throw plastic Indian toys on the ice. These dehumanizing experiences remind Saul of his place on the margins, on the team and in society generally.

Frustrated, Saul chooses to abandon the game he loves. He turns to a life of alcoholism and hard labour, hoping to escape the pain of being tore away from his family and growing up in a residential school. Yet, Saul eventually seeks help and chooses to confront his past, including coming to terms with the sexual abuse he experienced at the hands of Father Gaston (which is implied earlier but is only confirmed towards the end of the film). The emotional conclusion sees Saul reconnect with the land and his culture and return to the game he loves.

Indian Horse is a powerful film and one that all Canadians need to see. It can serve as an antidote to the growing trend of residential school denial catalyzed by Senator Lynn Beyak.

Many Canadians, as Mohawk scholar Taiaiake Alfred has noted, are in denial about the history of colonialism. Some settlers prefer to cling to selective and self-congratulatory stories about Canada as a “Peaceable Kingdom” that justify their ongoing occupation of Indigenous territories as normal and natural. Canadians are unwilling to acknowledge the truth that their country is part of the brutal and bloody global process of dispossessing Indigenous peoples from their lands to create deeply unequal capitalist settler societies. Indian Horse demonstrates that residential schools played an important role in this process and also highlights how the legacy of the schools continues to shape Indigenous-settler relations in Canada today.

Overall, Indian Horse is a must-see movie that challenges Canadians to confront the legacy of Indian Residential Schools and reflect on how they can end anti-Indigenous racism and build meaningful relationships with Indigenous peoples. So, take a break from watching the NHL playoffs and check out Indian Horse’s more meaningful hockey storyline.

Sean Carleton is an Assistant Professor in the Department of General Education at Mount Royal University in Calgary, AB, Treaty 7. He is a historian of settler colonialism, capitalism, and the rise of state schooling in Western Canada.