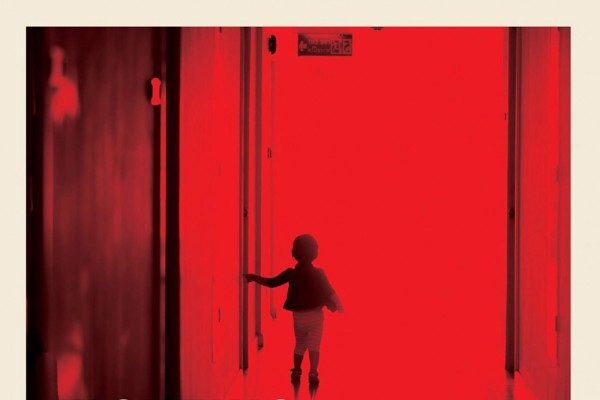

Like the Sound of a Drum

Review: Like the Sound of a Drum: Aboriginal Cultural Politics in Denendeh and Nunavut

by Peter Kulchyski University of Manitoba Press, 2005.

During the Berger Inquiry of the 1970s, held ostensibly to determine the actual opinions of Dene and Inuvialuit populations regarding a proposed Mackenzie Valley gas pipeline, a famous intervention was made by Philip Blake of Fort MacPherson:

“Look at us, and what we stand for, before you accept without further thought that the Indian nation must die. I believe that your nation might wish to see us not as a relic from the past, but as a way of life, a system of values by which you may survive in the future. This we are willing to share.”

Peter Kulchyski, Native Studies professor at the University of Manitoba, took up this challenge through many years living in the north, most notably in the communities of Panniqtuuq, in Nunavut, as well as Fort Good Hope and Fort Simpson, in Denendeh (Northwest Territories). The results can be found in his book, Like the Sound of a Drum (University of Manitoba Press, 2001).

Kulchyski explains what he sees as political. He describes the day-to-day differences born of the history of a community – small, tight and living in harsh conditions – as well as the structures of the political realities of councils and chiefs, and even the “Balkanization” of Denendeh into small entities like the Sahtu and Dehcho regions, and others.

Especially since the Berger Inquiry, politics in Denendeh have been shaped by two processes – processes that really are joined at the hip. The first is the various forms of “final status agreement” negotiations either ongoing or already carried out between nations within Denendeh. The second is planning for the (in)famous Mackenzie Valley Pipeline.

Leaving the decisions around such matters up to the peoples of the Valley themselves, Kulchyski offers little by way of a critique of the proposed pipeline. He does point out that it appears ever more likely that more people from the communities of the valley will work for the various planners; that it will greatly affect the landscape in Denendeh; and that the gas is destined to flow to fuel the extraction of the Alberta tar sands – perhaps the single-most dubious development on the planet.

The other process involves the breaking-up of the once-united Dene Nation into many, dividing the two communities of Fort Good Hope and Fort Simpson. Citing the many differences – especially the size of the white settler population in Fort Simpson and the isolation of Fort Good Hope – Kulchyski concludes that the separation of these communities represents the aspirations of the local populations. Yet, this seems short-sighted. The plans for building the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline entail a massive influx of southern workers, as well as the construction of the highway north of the small community of Wrigley, all the way to Tsiigehtchic (where the Peel River meets the Deh Cho in the Arctic). This will diminish the differences that today exist between the two communities. These differences can only be preserved by stopping the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline forever, and under all circumstances. Yet, as mentioned earlier, Kulchyski appears unwilling to directly oppose the pipeline.

Overall, Kulchyski’s treatment in this book is painstaking. He leaves a reader with the feeling that the voices heard are of those who live in Denendeh and Nunavut, as they have since time began and the earth was new. Read this book and learn why, in Philip Blake’s words, the lives of the people of Denendeh may indeed offer, “a system of values by which you may survive in the future.”

This article appeared in the Indigenous Lands and Rights issue of Canadian Dimension .