Settler colonial solidarity and me

A personal reckoning with how childhood lessons in empire and whiteness help explain Western loyalty to Israel

Siege of Vienna, 1683. Illustration by Peter Dennis/Osprey Publishing.

Many of us wonder why so-called Western countries continue to support Israel with financial and military help despite its two-year-long genocide in Gaza and the West Bank.

Of course, we all know that Israel is an aircraft-carrier for Western imperialism in the heart of one of the world’s most strategically vital regions. Yet that alone does not explain the deep and persistent emotional attachment that Western politicians and populations have for Israel as that country commits crimes against humanity and imperils even itself. Holocaust guilt among Western Christians has long been cited as another factor, but that rationale wears thin in the face of the live-streamed slaughter unfolding today.

A friend of mine suggests that settler colonists are instinctively inclined to support other settler colonists.

At first I dismissed that idea as too reductive—surely global politics and state policies can’t be explained away as subconscious psychological affinities. But the more I sit with it, the more sense it begins to make.

For those unaware of the meaning of settler colonialism, or doubtful about its application to Israel, it is, quite simply, defined as:

…the logic and operation of power when colonizers arrive and settle on lands already inhabited by another group. Importantly, settler colonialism operates through a logic of elimination, seeking to eradicate the original inhabitants through violence and other genocidal acts and to replace the existing spiritual, epistemological, political, social, and ecological systems with those of the settler society.

As for solidarity among settler colonists, I’ll illustrate this with an example from my own life.

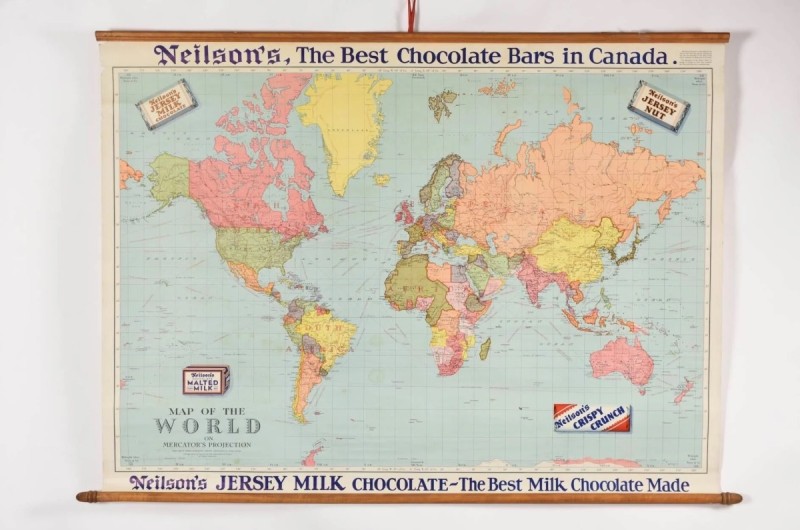

I grew up as a white settler colonist—or at least as someone who benefited from the privileges created by earlier ones—in Canada. I still remember the Neilson’s Chocolate world map hanging in my classrooms, emblazoned with the slogan “The Best Chocolate Bars in Canada.” The map showed the British Empire (later the Commonwealth) in pink, spread proudly across the globe. Those of you of a certain age may recall it. As a child, my heart swelled at the sight of so many countries shaded the same colour. It felt good to be on the winning team.

The impact was palpable. Despite the fact that I have been an anti-imperialist, and an anti-Zionist Jew for more than half a century, I am still subconsciously imbued with biases acquired in my childhood. And I’ll bet you are too. We just don’t like to admit it to others, or to ourselves.

Here’s a case in point, and bear with me for a small history lesson.

Neilson’s chocolate world map, 1956.

A few years ago I was reading a book about the so-called “Second Siege of Vienna” in 1683, during which the armies of the Ottoman Turkish empire surrounded the city that their leader, Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa Pasha, called the “golden apple.”

In the 14th century, the Ottomans launched an expansion deep into Europe, subsuming the Balkan states of Bulgaria, Serbia, and Byzantium before seizing Constantinople in 1453, the great Christian stronghold of the East. By 1529, under Suleiman the Magnificent, an army of 100,000 advanced on Vienna, the seat of the Holy Roman Empire and the symbolic prize of their long campaign. That first attempt failed.

A century and a quarter later, however, the Grand Vizier returned with 200,000 troops, among them the formidable Janissary shock regiments. Like other imperial powers—think of the Scots or Sikhs conscripted into the British Empire—the Ottomans drew warriors from once-hostile populations. In this case, young Balkan Christians were converted to Islam and forged into an elite corps, serving as both fighters and guardians of the empire.

The Ottomans almost succeeded this time, with an array of advanced military and armaments and by tunneling their way under the walls. After two months, the city was about to fall, when a relief force, a coalition of Christian Habsburg and other European armies, called the “Holy League,” led by the Holy Roman Emperor, attempted to break the siege.

The Christian warriors prevailed and Vienna was “saved.”

Over the next several years, those Christian armies chased the Turks back through the Balkans, re-taking territory that had been part of the Ottoman Empire for almost three centuries. Despite several more centuries of empire, this was the beginning of the end for the Ottomans.

One of the key violent encounters of the campaign through the Balkans occurred at Belgrade, Serbia in 1688. The Holy League laid siege to that city, one of the key strongholds in the Ottoman presence in Europe.

As I am wont to do, I looked up the array of forces on either side.

And to my great surprise, whom did I find fighting on the Ottoman side but the Jewish population of Belgrade!

The Jews of Belgrade saw the attacking Christians not as potential liberators from the Muslim rulers, but as enemies, to be fought against alongside their Muslim neighbours. On the other hand, many Christians under Ottoman rule, fought alongside their co-religionists in the Holy League.

In 1688, the Christians prevailed. The Jewish community of Belgrade paid a heavy price: the Holy Christian Warriors sacked the Jewish quarter, killing many, taking others captive to be ransomed by Jewish communities elsewhere. Many fled alongside the retreating Ottomans.

A thunderbolt hit me.

As I read the book, I realized, unsettlingly, that deep down I had been subconsciously rooting for the Christians!

Yet “my people,” the Jews of the Ottoman Empire living in Belgrade, chose to fight for the Ottoman Muslims and not for the Christian so-called “liberators.”

Why? Because Jews had lived for centuries under Muslim rule. The Ottoman Turks—like their Muslim counterparts across southern Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa (today called West Asia and North Africa, or WANA)—generally treated Jews and Christians with respect as “people of the book.” They were taxed more heavily than Muslims, but for the most part spared abuse, and in many places, especially under Ottoman rule, Jewish communities thrived.

Life in Christian Europe was a very different story. Beginning with the bloody pogroms of the Crusades, Jews were forced into ghettoes, massacred, and expelled. No wonder the Jews of Belgrade stood with the Ottomans: they knew all too well what awaited them under Christian “mercy.” In fact, many Jews who flourished under the Ottomans had originally arrived there after being driven out of European Christian lands in the late Middle Ages.

The Israeli-British scholar Avi Shlaim, famous as a “new historian” of Israel, tells this story well in his recent book, Three Worlds: Memoir of an Arab Jew. He was born in Iraq in 1945, but his family roots go back 2,600 years in that country. They were prosperous, well-respected and well-integrated members of the Arab community, which is why Shlaim can call himself, without hyperbole, an “Arab Jew.”

It was only in the mid-20th century that Iraqi Jews began to face serious discrimination—driven largely by British control and exploitation, the ambivalent role of Jews within that system, and above all the violent dispossession of Palestinians during the creation of Israel and the Zionist defeat of the Arab armies, including Iraq’s. Like most Iraqi Jews, Shlaim’s family was eventually forced into exile, resettling in Israel.

Iraqi Jews arriving in Israel on a flight from Cyprus, September 1950. Photo courtesy the National Photo Collection of Israel/Wikimedia Commons.

Shlaim’s family lost its fortune and, seen as the “Arabs” they were, fared poorly in a new country dominated by European Ashkenazi Jews. Israel’s first Prime Minister David Ben Gurion made his disdain for Mizrahi emigrants clear: “We don’t want Israelis to become Arabs.” Young Avi, in particular, was miserable—mocked and insulted by classmates. Though he later returned to complete his compulsory military service, he eventually settled in the UK, where he has become a leading anti-Zionist critic.

Shlaim’s book also exposes a hidden factor in the Jewish exodus from Iraq. As in Egypt and elsewhere, Israeli intelligence in the 1950s carried out “false flag” operations—bombings of Jewish and American institutions—designed to frighten Jewish populations into emigrating and to disrupt ties with the United States.

Seen in this light, the decision of Belgrade’s Jews to fight alongside their Muslim rulers is no mystery. What is more striking is how, deep in my subconscious, I found myself rooting for the Christians—until the illusion cracked. Those of us raised in imperial centers or settler colonies like Canada, the US, and Australia carry an ingrained loyalty to those we perceive as “like us”: other settler colonists.

And, truth be told, “like us” also means white. As scholars critical of racist regimes explain, ideas of whiteness are not always attached to the colour of one’s skin. It is an ideology that conscripts people from certain ethnic groups into a fictitious category that justifies their privileges. Those of us admitted into whiteness are taught to sympathize with other people who have been admitted into the “club” of whiteness, and to demonize or devalue people who are not white. This ultimately serves the ruling class and the dominant social order.

In Canada and other “Western” countries, some Jews (particularly those of Ashkenazi heritage, like me) who were once excluded from whiteness are, today, largely considered (and consider themselves) white. That happened in my lifetime, and my schooling as a proper imperial subject was part of the process by which my family and I effectively became white: not only in Canadian society’s eyes, but in our own. With that came the internalization of settler-colonial ideology—a loyalty to other white people, and a racist devaluing of non-white lives.

My “Siege of Vienna” moment has hastened my understanding of why Western leaders, sharpened by guilt for the Holocaust, would tolerate Israeli malfeasance and flouting of so-called international law. If I, a Jew, was rooting for the white Europeans, then it’s easier to understand why Western publics cheer on the white Europeans they imagine in Israel, locked in a “holy war” against the brown infidels—even though, in reality, more than half of Israel’s Jewish population is Mizrahi.

Larry Haiven is Professor Emeritus at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax and a founding member of Independent Jewish Voices Canada.