Poisoning the well: the toxic Cold War legacy of Winnipeg’s aerospace industry

Decades of chemical dumping and corporate impunity have turned a major aerospace hub into a long-term environmental disaster

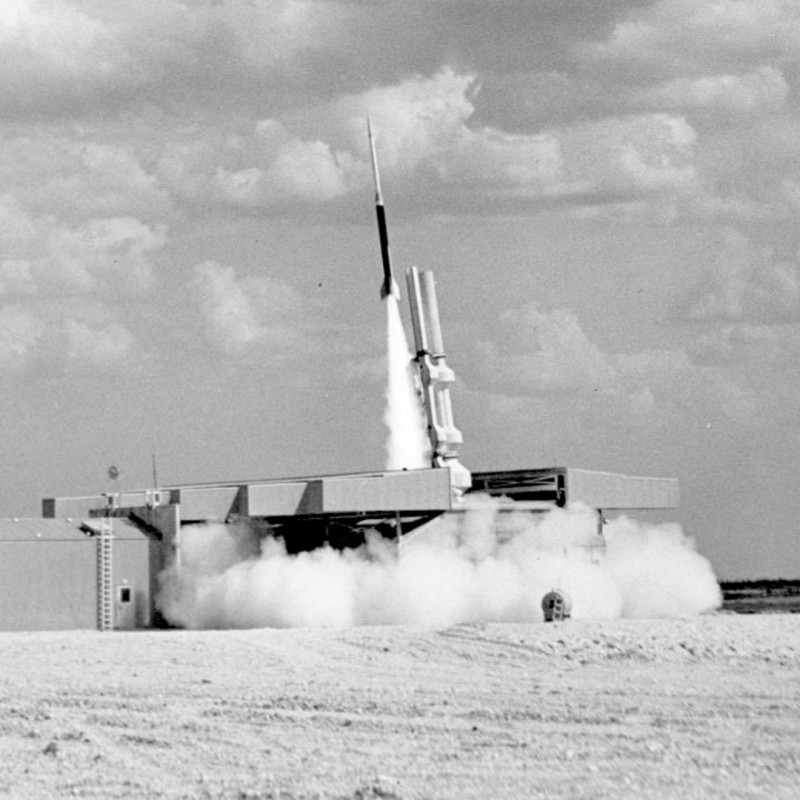

Black Brant IV rocket launched from the Churchill Rocket Range, c. 1960s. Photo courtesy the Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada/Facebook.

In early 2025, the Manitoba government announced it would provide $17 million in loans and grants to the Winnipeg operations of Magellan Aerospace, a Mississauga-headquartered company that is majority owned and chaired by billionaire and oilsands baron N. Murray Edwards. The most immediate concern with this substantial corporate subsidy is that Magellan’s Winnipeg facilities are a major manufacturer of key parts for Lockheed Martin’s F-35 fighter jets, which are heavily used by Israel in its unrelenting assault on Gaza. Troubling as this is, however, there is a lesser-known reason to question this public handout.

In the early 1990s, Bristol Aerospace—then owned by Rolls Royce—was found to have poisoned an aquifer beneath its Rockwood Propellant Plant near Winnipeg with high concentrations of toxic and carcinogenic solvents, including one, trichloroethylene (TCE), that was recently banned by the US Environmental Protection Agency due to health risks such as “developmental toxicity, reproductive toxicity, liver toxicity, kidney toxicity, immunotoxicity, neurotoxicity, and cancer.” Only a few years later, in 1996–97, Edwards increased his investment in a languishing Ontario airplane manufacturer, renamed it Magellan, and bought up Bristol in an acquisition spree that helped establish the company as one of the largest aerospace producers in the country.

Since then, building on Bristol’s experience and reputation, Magellan’s operations in and near Winnipeg have cemented the company as a major player in the manufacturing of systems and parts for commercial airplanes, military jets and helicopters, satellites, and rockets. In 2024, Magellan reported almost $1 billion in company-wide sales and more than $35 million in profit, with facilities throughout North America, Europe, and India.

Yet decades after it was first discovered, the groundwater pollution caused by Bristol remains so extreme that more than 100 square kilometres of the region in and around Stony Mountain is now formally (and euphemistically) designated as the “Rockwood Sensitive Area,” where most uses of well-water are prohibited. Some private residences and agricultural producers continue to use it, including a Maple Leaf hog supplier and a Hutterite colony.

Remediation efforts in the years since—a process of “air stripping” that separates the toxic compounds from the water and releases them into the atmosphere—have significantly lowered contamination from the initially staggering levels. However, average concentrations still exceed recommended limits by more than tenfold (and surpass stricter guidelines by over 150 times). There are also several sites in the area where pollution is increasing, not decreasing, likely due to complex groundwater flows.

Neither Bristol nor Magellan have ever faced lawsuits or fines for the contamination. Today, the province appears to systematically avoid even naming the company in its limited information about the disaster, simply referring to it as “an industrial site (locally known as the Rockwood plant).” Now, the Manitoba government has handed the company that bought Bristol—including its environmental liabilities—even more public funding, as if this catastrophe never occurred.

Dr. Eva Pip, a retired full professor of biology and water quality expert at the University of Winnipeg who has followed the Rockwood pollution crisis since its beginning, shared her thoughts in an email interview with Canadian Dimension: “The passage of a great deal of time has eroded and erased this issue from public awareness—the current generation was not even born when this event happened—even though there has still been no final resolution or closure, despite long and very expensive endeavor,” she said. “This torpor has even extended to government.”

‘Everything is so downplayed out here’

A federal site inspection first discovered pollution beneath Bristol’s Rockwood Propellant Plant in 1991. Since the early 1960s, Bristol had produced millions of pounds of fuel to support its production of rocket systems—including the renowned Black Brant sounding rocket used for upper atmospheric research by NASA, and the CRV7 air-to-surface rocket used by many NATO fighter jets and attack helicopters.

Throughout the 1980s, Bristol was Canada’s largest exporter of military goods and a key participant in the national Munitions Supply Program (MSP) as one of five companies supplying arms to the Canadian military—a role Magellan continues today through its production of rocket systems and flares. The CRV7 rocket, manufactured at the Rockwood plant, was Bristol’s primary defence commodity, widely sold through both export markets and the MSP, and saw extensive use in the Gulf War and the war in Afghanistan.

One of the major motivations for the Rockwood plant’s original siting was that its “rural location afforded the necessary buffer zones to ensure public safety from an accidental explosion.” But its relative isolation also facilitated the systematic dumping and burning of solvents and rocket propellant over the course of several decades. This occurred despite the area having been identified as a “groundwater pollution hazard zone” because only a thin layer of clay covered the highly porous bedrock through which water easily percolated.

A British Army AugustaWestland Apache AH.1 attack helicopter of the Army Air Corps in Afghanistan fires CRV7 rockets during a patrol in 2008. Photo by Staff Sergeant Mike Harvey/Ministry of Defence/Wikimedia Commons.

Bristol initially pleaded ignorance, appealing to occasional chemical spills that it had reported to regulators. However, only two weeks after the discovery, five former workers at the Bristol plant blew the whistle to the Stonewall Argus, detailing that “spent rocket fuel, raw sewage, degreasers and highly volatile oxidizers” were routinely dumped into an unlined disposal pit. One worker told the Argus, “I said to the safety and security officer that this isn’t the proper disposal means, and I was concerned about 20 years from now.”

During what the Winnipeg Free Press described as a “stormy public meeting” with the company and province at Stony Mountain’s curling rink in early 1992, a resident whose water had been poisoned quoted from a report published in 1949 that warned of the likelihood of large-scale usage of the same industrial solvents leading to groundwater contamination. A former worker at Winnipeg’s Bristol plant in St. James also claimed that the company had dumped chemicals into the sewers over the course of the almost three decades that he had worked there.

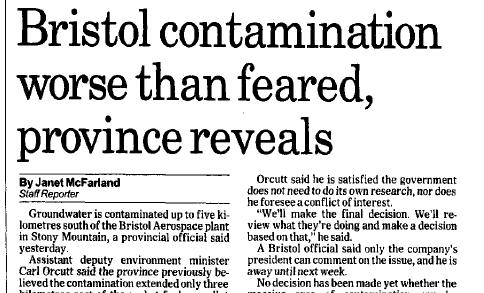

Residents of the area were predictably outraged and concerned about the news when it first emerged, with the compounds already regarded at the time as potentially cancer-causing. One resident, Gil Rieve, told the Free Press: “We don’t know what’s down there, how much there is, what the health risks are, how it can be cleaned up or if it can be cleaned up.” Two months later, when further investigation found that the pollution plume extended well beyond its originally estimated size, Rieve explained: “Everything is so downplayed… Bristol has contaminated the water, and yet it’s like nothing happened out here.”

An unofficial public-private partnership

From the get-go, Bristol and the province collaborated to minimize the severity of the situation. In the first Free Press coverage of the poisoning, Interlake Chief Medical Officer Joel Kettner, who later became Manitoba’s top public health official, assured that “nobody has suffered any symptoms or illness related to exposure to high concentrations of these chemicals” and that “in the main, the people can be reassured that the health risk for this is low.”

Winnipeg Free Press clipping, 1992

For its part, Bristol offered to cover the costs of having filters installed in the homes of impacted residents but refused to discuss the claims made by whistleblowing former employees. In response to a news article about the collapse of the local real estate market due to fears of contamination, Bristol President Trevor Murch claimed: “Once we’ve been able to show there’s no health concerns with the water, they shouldn’t have problems being able to sell.” Murch also explained that the goal of testing Bristol workers for long-term health damage was to “reassure our workers that there’s no problem with their liver function.” During the 1992 meeting, attended by more than 300 people, Murch replied to a shouted question about whether he would drink the contaminated water daily by saying, “It wouldn’t worry me because I take doctor’s advice on these issues and so should you.”

While assuring that Bristol would cover some of the costs from replacing the clean water supply of residents, local Progressive Conservative MLA Ed Helwer told the Free Press in early 1992: “The company is a good corporate citizen out there and employs over 100 people in the area. We need the jobs, but at the same time, the company has to adhere to all the requirements.”

Bristol’s contracted report into the contamination identified six “hot spots” where solvents had leached into soil and likely into the aquifer. In particular, the site where Bristol had burned solvents and rocket propellant over the previous three decades had been found to have the worst contamination, and was thought to account for the plume extending well east of the plant.

Bristol maintained that the southward plume remained unattributable to its activities. In response, a spokesperson for the newly formed Stony Mountain Association Against Aquifer Contamination (SMAAAC) criticized the report for claiming that the southern-most plume was disconnected from the contamination nearer the plant, stating that “I feel they are going to be found responsible but it’s going to take another study to find out who is exactly responsible.”

To this day, Magellan and its contracted engineers deny that an “orphan plume” of TCE southeast of Stony Mountain is attributable to Bristol’s historical dumping, stating “this plume is not the responsibility of Magellan.”

Activists from Mennonite Action protest in front of the entrance to Magellan Aerospace’s Winnipeg facility, formerly known as Bristol Aerospace. Photo courtesy Mennonite Action/Instagram.

Remediation ‘will not be completed in our lifetimes’

In July 1992, the government of Manitoba, Bristol, and Rockwood struck a deal. The province would build a new water pipeline to the area to replace the permanent loss of well water. However, Bristol would only have to cover 25 percent of the cost, or $200,000, which it justified as “there’s no definite proof it is solely responsible for the contamination.” The federal and provincial governments would pay the remaining $600,000. Bristol would also split the annual maintenance cost of the pipeline, estimated at $12,500 per year, with Rockwood for the following 15 years, meaning that each resident would pay between $10 to $12 a month. In total, this meant that Bristol—and soon, Magellan—only had to pay a total of $300,000 in pipeline costs.

In response to this deal, an impacted resident argued that “they’re treating Bristol with kid gloves, I’m not sure why.” Elsewhere, a Winnipeg-based water activist noted “I am concerned whether the polluter is being forced to meet its obligations and if the governments involved are taking a strong enough stand.” In 1995, provincial environmental legislation emphasizing the “polluter pays” principle once again drew attention to the Bristol contamination. The NDP’s environment critic argued, “They are the ones that are liable for the contamination, yet we as taxpayers in the province of Manitoba are picking up a large portion of those costs.”

Despite ongoing concerns about impacts on air quality—including the potential emitting of hydrochloric acid and phosgene, which was used as a chemical weapon during the First World War—the province restored Bristol’s burn permit in August 1992 to incinerate waste fuel. In total, Bristol planned to burn about 40,000 pounds of rocket fuel over the course of 50 or so burns. Residents and environmentalists highlighted the plant’s proximity to Oak Hammock Marsh, the site of massive bird migrations in the fall and spring. Dr. Hymie Gesser, a chemistry professor at the University of Manitoba, denounced the burn, saying “They have never properly monitored a burn by analysing the gases that are released. From what I gather, they did some magical calculation.”

Magellan has continued to burn explosive contaminated materials in the decades since. In 2021, it bid on a contract to decommission CRV7 rockets that would help in “reducing the amount of pollutants released on site from the currently approved open burning disposal.” However, it is unclear if this facility was ever built; the proposed location in the company’s provincial application remains empty in recent Google Earth images.

Rockwood Propellant Plant, as seen using Google Earth.

Since 1994, Bristol and Magellan have been required to operate a groundwater remediation system and provide regular reports to the provincial environment department. The last monitoring report was published in June 2023, covering the year 2022; although only operating for five months of the year, it extracted and treated almost 600 million litres of water. Despite this, concentrations of toxic chemicals remain exceedingly high, results that Pip described as “disheartening” but “not unexpected, due to the size of the contaminated plumes, the heterogeneous and complex patterns of groundwater flow, and involvement of a number of different compounds among which effectiveness of removal varies.”

The professor concluded: “One can only speculate on the future timeline for remediation of the aquifer; it depends on whether we expect complete (i.e. not detectable levels), or only adequate (i.e. below guideline limits) remediation. In any case, the process is very slow, of variable effectiveness for different compounds, and will not be completed in our lifetimes.”

Subsidizing a corporate polluter

Winnipeg is far from the only place to have its water poisoned by industrial solvents used by aerospace and military companies. Magellan has described having implemented “remedial systems… to address trichloroethylene-impacted groundwater” at its operations in Mississauga, Fort Erie, and in the UK. The company has also reported that “neighbouring property owners to the Corporation’s sites at Winnipeg, Manitoba; Mississauga, Ontario; Fort Erie, Ontario and Queens, New York have been made aware of potential off-site impacts of trichloroethylene and environmental investigations at those sites,” but that “negotiations with the neighbouring property owners have precluded the need for off-site remediation.”

Beyond Magellan, numerous cases of high TCE contamination have been documented in and around military bases across Canada and the United States. A recent study found that exposure to TCE increases the risk of developing Parkinson’s Disease by 70 percent. Like many forms of industrial pollution, this environmental crisis is difficult and costly to remediate once the damage is done. Yet rather than seeking compensation or confronting the broader socioecological consequences of militarism, the Manitoba government has chosen to ignore this toxic legacy—continuing to subsidize the very corporation responsible, now positioning itself to profit from surging military budgets.

James Wilt is a Winnipeg-based PhD candidate and freelance writer. His latest book is Dogged and Destructive: Essays on the Winnipeg Police.