Does the Right to Strike Still Exist?

Some things never change. Another summer is upon us, and children are enjoying their break from school; the baseball season is well under way; and the Conservative government is continuing its attack on working people. Last summer, as you may recall, the then newly-elected Conservative government responded with a heavy-hand to three labour disputes: one at Canada Post and two at Air Canada. In all three of these instances, the government sought to eliminate the right to free and fair collective bargaining and the right to strike. As the government’s recent actions in the strike launched by the Teamsters Union against Canadian Pacific Railway illustrates, the right to strike and the related right of free collective bargaining appear to be in jeopardy in industries regulated by the federal government. As a result, we are forced to seriously ask ourselves: does the right to strike still exist at the federal level?

Shortly after their election in May 2011, the federal government introduced back-to-work legislation to end a lockout by Canada Post. While this action didn’t constitute an attack on the right to strike, per se, it did represent an attack on free and fair collective bargaining, as the government mandated a wage-settlement that contained increases that were significantly below Canada Post’s last offer to the union, and appointed an arbitrator to resolve all outstanding disputes. After a resignation by the first arbitrator, who lacked the ability to speak French, the government proceeded to appoint Guy Dufort, a former Conservative Party candidate and former management-side labour lawyer who previously represented Canada Post in a long-standing pay equitydispute involved Canada Post and its employees as the replacement arbitrator. Such an appointment hardly upholds the standards of independence and neutrality that is central to the arbitrationprocess.

Although it did not formally pass back-to-work legislation in either of the disputes involving Air Canada last summer, it did table such legislation and was certainly ready to pass it. Recognizing that their right to strike would quickly be extinguished if exercised for any length of time (and the possibility of a mandated wage settlement and biased arbitrator), the CAW and its members employed in sales and services quickly came to an agreement with Air Canada. Despite the ‘successful’ negotiation of a collective agreement without a work stoppage, the threat of back-to-work legislation certainly worked against the union’s interests and provided Air Canada with important leverage in the dispute. The right to strike at the federal level was certainly thrown into question with the almost immediate introduction of back-to-work legislation after the CAW announced its plans to launch a strike.

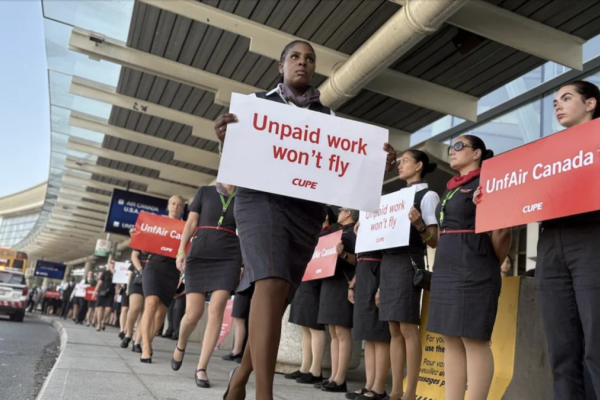

The third incident involved flight attendants employed at Air Canada and represented by CUPE. The unionized flight attendants were threatening a legal strike after twice rejecting offers from Air Canada. Before these workers had the opportunity to hit the picket lines andexercise this right, federal Labour Minister Lisa Raitt enacted a procedural move by referring the dispute to the Canada Industrial Relations Board (CIRB), thus making the strike illegal until the Board ruled otherwise. Recalling the imposed settlement on CUPW members employed at Canada Post and similarly fearing the repercussions of waging a strike (legal or illegal) against the Harper government, CUPE reluctantly agreed to binding arbitration with Air Canada to resolve the dispute. Paul Moist, CUPE’s national president Paul Moist, rightly referred to this ploy as an “outrageousinterference by the Harper government” in the collective bargaining process. It also represented yet another attack on working people and their right to strike. In this case, before workers could even exercise this right, it was made illegal.

The seasons may change, but the government’s approach to labour relations – and more specifically the right to strike – does not. Fall came and went, so too did winter, but not before the government once again interfered into the collective bargaining process. Again, Air Canada was the site of the dispute, and the government’s heavy-handed approach once again threw into question the practical existence of the right to strike at the federal level.

In March, 2012, pilots (represented by the Air Canada Pilots Association) and technical, maintenance, and support workers (represented by the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers) were in the process of attempting to renegotiate their collective agreements, which had expired in 2009 and 2011 respectively. Both unions were threatening job action, especially the IAMAW, and Air Canada was contemplating locking out its pilots. Much like she did in the Air Canada/CUPE dispute, Labour Minister Lisa Raitt referred the dispute to theCIRB, which effectively prevented the unions from carrying out their threat to strike. A week later, Raitt introduced back-to-work legislation in the form of Bill 33 (An Act to provide for the continuation and resumption of air service operations).

Not only did the bill eliminate the possibility of a legal strike, it also interfered in the collective bargaining process by sending all outstanding issues to a biased arbitration process. In justifying the legislation, Raitt arguedthat “a work stoppage at Air Canada will take a toll on our fragile economy [which] we simply can’t afford,” but added that “grounded flights translate into…frustration for stranded travellers.” For the third and fourth times at Air Canada (and the fifth time overall in a mere eleven months), employers were taken off the hook from negotiating a collective agreement with their employees, and workers were denied the right to withhold their labour. Of Raitt’s action, NDP Labour critic Yvon Godin correctly observed that the government is “sending a strong message to business that they don’t have to negotiate.”

Although the government’s decision may have prevented a legal work-stoppage, it hardly solved outstanding issues between Air Canada and its unions, and did nothing to improve a fractious work climate at the airline. In fact, it appears to have made it worse. Although the legislation may have prevented a legal work stoppage, it – like back-to-work legislation more generally – cannot prevent an illegal work stoppage. A mere two weeks later, workers whose rightto strike had been denied heckled and applauded sarcastically as Raitt walked through Pearson Airport in Toronto. This prompted Air Canada to issue 72-hour suspensions to the workers, which in turn prompted a wildcat strike by members of the IAMAW in Toronto, Montreal, andVancouver. In turn, 37 workers were terminated for participating in the illegal strike. In an effort to save face and avoid fines of $100,000 per day, the union distanced itself from the strike and quickly urged its members back to work. Although the strike was quickly ended (and the terminated workers were reinstated), the courageous actions of rank-and-file members whose right to strike had been thoroughly trampled represented a rare glimpse of a militant wildcat strike. It also illustrated a growing dissatisfaction amongst workers with the government’s draconian approach to labour relations, and the fact that the passage of back-to-work legislation cannot fully ensure that a labour stoppage will not occur. Now, after just over a year in office, the Conservative government has once again ramped up its attack of organized labour and the right to strike in a dispute involving Canadian Pacific Railway and the Teamsters. At issue in the dispute were CP’s demands to reduce retirement benefits and restructure the workers’ pension plans, as well as issues involving a work-life balance. As the Teamsters launched a legal strike on May 23rd, Labour Minister Lisa Raitt once again wasted no time in hinting toward the passage of back-to-work legislation and the imposition of binding arbitration to end the strike and settle the contract. She claimed that the government was “cognizant of the effects on the economy and on their businesses and we are ready to act”, maintaining that if the parties were unable to come to an agreement on their own terms, “then you are going to get stuck with a parliamentary process.” By parliamentary process, of course, Raitt was referring to back-to-work legislation and binding arbitration, both things that Canadian Pacific was in favour of and that the union was opposed to.

Although Raitt spoke of the slow pace of negotiations, such is the result when the government is threatening back-to-work legislation, especially when one of the parties (in this case CP) is in favour of having the dispute settled by arbitration. In fact, as NDP labour critic Yvon Godin rightly noted of the passage of back-to-work legislation in March, the government is illustrating to business that they need not negotiate – at least not in any meaningful way – as the they will soon step in an end the process in a way that strips workers of their rights and tilts the balance of power infavour of management. In short, the approach is delay, delay, delay until some sort of ‘economic emergency’ can be construed, and then legislate strikers back-to-work. Rather than speed up negotiations and promote good-faith bargaining, the government’s overt threat of back-to-work legislation only serves to slow-down the negotiation process and provides management with the ammunition it is often looking for. As NDP leader Thomas Mulcair aptly noted, the government is “giving a pattern to employers: ‘don’t bother negotiating.’ What possible incentive exists to an employer who knows that the final result will always be that the Conservatives are going to bring in special legislation to vote people back to work? So they have no incentive to deal in good faith, to bargain in good faith.”

The government was so determined to pass back-to-work legislation to end the Teamsters’ strike that it fast-tracked the legislation through the House of Commons, and its passage was slowed – only slightly – by procedural rules in the Senate. The government used its majority status to limit debate in the House, thus preventing a filibuster by the opposition that would have delayed its passage by three days, as was the case with the back-to-work legislation passed to end the Canada Post lockout.

After just over a year in office, the Conservative government has effectively ended six work stoppages or potential work stoppages through the passage of, or the threat of, back-to-work legislation. Certainly this aggressive movement to restrict the rights of Canadian workers is nothing new. In fact, as the Canadian Foundation for Labour Rights has noted, there have been 197 laws passed by the federal and provincial governments that have restricted, suspended or denied workers their collective rights to join unions, bargain collectively, and strike. The current government has passed three such laws since its election in May 2011 (and has threatened to do so in another two instances). In short, they – like many other governments since 1982 – have effectively eroded the rights of workers.

There is something different about the current government however. Their attack on the right to strike (and theright to free and fair collective bargaining) represents an unprecedented attack against workers’ rights in Canada. The frequency with which the current government has passed (or threatened to pass) back-to-work legislation is one thing. That it is part of a broader ideological project to undermine the collective action of workers and their unions is another. Taken together, the right to strike is under attack, and we have reached the point where it must be asked whether or not the right to strike still exists in industries regulated by the federal government.

The right to strike is a legislative right, meaning that it is granted to workers by legislation. At the federal level in Canada, these rights are established by common law and under the Canada Labour Code and the Public Service Staff Relations Act. The right to strike is not, however, a constitutional right. Roy Adams, Professor Emeritus at McMaster University, has drawn an important distinction between these two types of rights, and correctly notes that a constitutional right is generally much more secure than a legislative right. What the legislature grants the legislature can take away. As a result, the passage of new legislation – such as a law ending a strike and forcing workers to return to work – can override the legislative right to strike. The right to strike, therefore, has always been precarious in Canada, although the willingness of the current government to override it suggests that its continued existence – at least under a majority Conservative government – is in jeopardy.

Governments of all partisan stripes have, in the past, legislated striking workers back to work in all ten provinces and at the federal level. Generally, however, they have done so sparingly and often only after lengthy strikes. What makes the current government different is the vigour with which they move ahead with back-to-work legislation. As soon as unions mention the possibility of a strike, the government is equally quick to mention the possibility of putting back-to-work legislation on the table. As soon as a strike is launched, the government has already drafted the legislation and moves ahead to pass it as soon as it legally can. The Canadian Press has referred togovernment’s use of procedural measures to curtail debate and fast-track the passage of back-to-work legislation as putting it “on Parliament’s equivalent of a red-eye bullet train.” The government’s willingness to defer the issue to the Canada Industrial Relations Board for absurd reasons – such as to determine if a strike by Air Canada workers jeopardizes the health and safety of the nation – suggests that they are willing to curtail the right to strike by virtually any means necessary. Of course, the government defends these measures by laying claim to an extraordinary or pressing circumstance in anattempt to justify their actions. Whether they are passing back-to-work legislation to prevent “a grave economic effect” (CP strike), “on behalf of small businesses [and] on behalf of charities who are being affected by this work stoppage” (Canada Post lockout), or to ensure smooth travel over March break (Air Canada pilots and mechanics), or the potential damage to a fragile economic recovery (cited in all uses of back-to-work legislation), the result is the same: an elimination of workers’ right to strike. The existence of these extraordinary circumstances is cited by the government as evidence that they are not opposed to allowing workers the right to strike per se, but rather, they suggest that they are unwilling to do so in the specific circumstance. Under this line of thinking, however, they seem to imply that they will allow workers to strike at some point again in the future, as soon as the dire or pressing circumstance passes.

In reality, however, this sort of argument could not be further from the truth and citing these dire circumstances is simply a red-herring. These attacks on workers’ rights are not the result of fragile economic recovery or possible grave economic effects, but are instead the product of an ideological battle against unions and collective action more generally, and a desire to erode the possibility of workers engaging in strikes altogether. In unmasking the Conservatives’ red-herring, it is useful to rely on the concept of ‘permanent exceptionalism,’ a term coined by political scientists Leo Panitch and Donald Swartz. This term suggests that governments will defend their oppressive actions as being the result of an exception or somesort of pressing or dire circumstance that demands their immediate action. For example, Stephen Harper’s comment that “as much as a side of me doesn’t like to do this [pass back-to-work legislation], I think these actions are essential” is telling of this sort of alleged‘exceptional’ act. The first part of the term, however, ‘permanent,’ suggests that there is always an exception to the rule, and that far from being one-off events, these exceptions become the norm as the government can always find a circumstance that demands immediate andharsh action, or will simply create one if there is not one that can be readily found. As the government’s actions over the past year show, Canada is in an era of ‘permanent exceptionalism’ and the right to strike at the federal level is in jeopardy.

What does this mean for organized labour going forward? With the right to strike under a continuous and hostile attack, and for all practical purposes non-existent, unions have lost their most effective weapon. Generally the threat of a strike (and an actual strike if need be) gives unions a meaningful bargaining chip in negotiations, which – interestingly enough – often leads to a negotiated settlement that is quick, fair and ultimately acceptable to both parties. Now, with a government more willing to use back-to-work legislation than any government in the past, that bargaining chip no longer exists and the tables have most certainly been tilted in favour of management. As R. Michael Warren, a former chief general manager at the Toronto Transit Commission and Canada Post CEO has aptly noted, “the ability of unions to negotiate is being weakened. Employers now know that they won’t be shut down for long, so they can more easily press for major concessions.”

At the end of the day, the assault on – and virtual elimination of – the right to strike has and will continue to hamper the labour movement in future negotiations. This is true of all workers in industries regulated by the federal government, and may be especially damning for federal civil servants represented by PSAC and PIPSC, many of whose contracts will expire prior to the 2015 election and will need to be renegotiated under the Conservatives’ watchful eye. The same is true for unionized transportation, telecommunication, and commerce workers, as well as workers in a handful of other federally regulated industries.

What, then, can unions do? Is the labour movement doomed to at least three more years of an unbalanced playing field? While there should be little doubt that the legal right to strike is unlikely to get unions far – as back-to-worklegislation will quickly be passed – unionized workers are not left powerless. As IAMAW members illustrated in March, a disenfranchised and frustrated rank-and-file may resort to an illegal strike in an attempt to exert influence on their employer. Such action is likely to be dealt with quickly by the government (and discouraged by the union), but remains one possible option. Parliamentary procedure by the opposition may delay the passage of back-to-work legislation, as it did with a three-day long filibuster during the Canada Post lockout, but the Conservatives’ usage of procedural rules has greatly muted the House and limited the effectiveness of parliamentary debate. Another option is a legal challenge under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, arguing that the passage of back-to-work legislation violates the fundamental rights of workers. While the likelihood of success is questionable, the lengthy process associated with a Charter challenge means that a ruling will not be handed down for a few years at least. Although in the long-term the promotion of the right to strike from a legislative right to a constitutional right would be in the interests of labour, this strategy is unlikely to provide any assistance to unions whose collective agreements will be negotiated in the upcoming months and years. Building alliances with like-minded allies who have also been victims of an ideological attack by the government (the women’s movement, Aboriginal groups, environmentalists, etc.) is also a useful strategy. Mobilizing rank-and-file members for public protest and demonstration is another necessary tool. A combination of a variety of options is ultimately labour’s best weapon, although there is no certainty of success.

One thing is for certain: while the right to strike at the federal level may exist on paper, it no longer exists in practice under the current government. While some things may never change, let’s hope that – like the seasons – this is something that does.