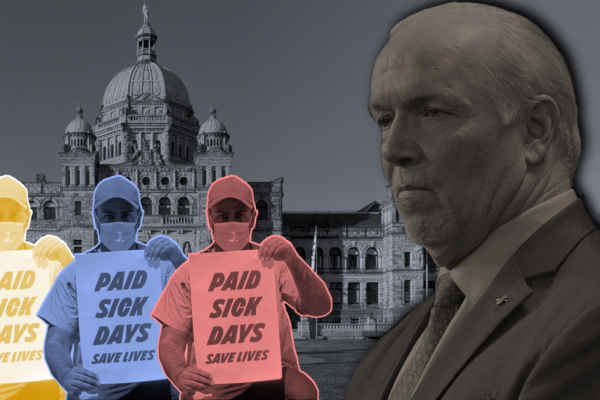

BC NDP fails people suffering from opioid use disorder

The province has fallen into familiar patterns with its willingness to use vulnerable populations as a political bargaining chip

Discarded drug use paraphernalia on the streets of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Photo by Ted McGrath/Flickr.

Late last year the British Columbia NDP narrowly defeated the Conservatives in the provincial election. The party’s takeaway from this victory, however, was not a renewed confidence in progressive policies. Like the Democrats in the United States and the Labour Party in the United Kingdom, their strategy has instead shifted to targeting vulnerable community members in the hopes of currying favour with voters who may be swayed by their adoption of cruel measures. The provincial government’s approach is on full display in its treatment of people with substance use disorders.

In April 2016 a public health emergency was declared in BC to help combat rampant drug overdose deaths, primarily from illicit synthetic opioids such as fentanyl. These drugs continue to claim lives at a catastrophic rate with deaths from opioid overdoses outpacing those during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Even before this declaration, the BC government had been a world leader in adopting progressive policies aimed at mitigating the harms of the crisis. The Crosstown Clinic in downtown Vancouver was the first of its kind in North America to offer prescription-grade heroin and a safe place to inject for people with opioid use disorder. Research has shown that this is an effective service, particularly for those who have found alternative treatments ineffective.

Despite such proven benefits, harm reduction policies were a dominant point of controversy throughout last year’s election. While the BC Conservatives confessed in their platform that measures like safe consumption clinics may be necessary “as a temporary and emergency measure,” the party took aim at several other key harm reduction initiatives. Specifically, they proposed ending safer supply programs and encouraged further use of involuntary treatment for people with substance use disorders. To the disappointment of many, the BC NDP took inspiration from these problematic proposals.

The take-home safer supply program was originally initiated by the government during the pandemic. This program enabled people with substance use disorders to be provided with take-home supplies of medications (such as oral hydromorphone) that could be used as alternatives to the toxic drug supply. This was done under the close supervision of trained health care professionals who oversaw the process. According to the government’s own report in 2023, the effects of this initiative were “largely positive,” though with more research warranted. An ethics review later concluded that “a safer supply policy can be ethically defended and prioritized.” This coheres with a study published around the same time that found that participation in the safer supply program for opioids was “associated with reduced overdose related and all-cause mortality.”

Despite these findings, the BC NDP announced a change to the program: safer supply could still be provided, but its administration had to be carried out at pharmacies rather than as take-homes. This was ostensibly to mitigate diversion to drug traffickers, but the only public evidence of this occurring is from a vague statement in an internal government slide deck leaked by the Conservative Party. Given such limited information, it is entirely unclear what this means or if significant diversion of prescribed opioids is taking place. In any case, to attack the program in the name of fighting potential knock-on criminal activity is to undercut essential support instead of addressing the underlying systemic causes of poverty and addiction.

While the government has not completely cancelled the program, its announcement is nonetheless a serious setback due to the fact that safer supply medications are often used several times a day. Under the new policy, a program participant has to make constant trips to the pharmacy for witnessed dosing. At best, these regular visits are extremely disruptive to people’s lives. At worst, users will find it impossible to participate in safer supply programs if they live in rural and remote areas, have mobility limitations, or use injectable safer supply medications, as pharmacies are not equipped to witness injections (specialized clinics also lack capacity to accommodate everyone who needs this service). Given such practical challenges, it is almost certain some people will drop out of the program and experience a fatal overdose.

The BC NDP has also taken inspiration from the Conservatives in expanding the use of involuntary treatment for people with substance use disorders. Outside of exceptional circumstances, involuntary treatment is an affront to personal autonomy, and will likely result in entrenched mistrust of the health care system. If involuntary treatment was radically effective, then we could, hypothetically, have a debate regarding whether such violations may sometimes be morally justifiable. But that debate is unnecessary because the evidence is entirely inconclusive as to whether involuntary treatment provides any benefit in this context. What’s more, people who undergo involuntary treatment may even be at an increased risk of overdose following discharge due to reduced drug tolerance.

To add insult to injury, every dollar spent on resources for this forced care is money not spent on other health services and social programs. These funds could instead go to making voluntary treatment more accessible or towards desperately needed social housing. Regardless of whether the money is used to improve society in order to dismantle the root causes of substance use disorder—or whether it is spent to improve existing treatment programs—it is clear that there is nothing sensible about coercing people into expensive programs that are unlikely to work.

The BC NDP has fallen into familiar patterns with its willingness to use vulnerable populations as political bargaining chips in hopes of appearing tough on certain issues. The government’s current approach not only harms community members affected by their policies, but also legitimizes the unfounded criticisms levied by the opposition. The BC NDP must refuse the temptation to throw those with substance use disorders under the bus and instead allow people to receive the evidence-based and humane care they deserve.

Blair MacDonald is a PhD student in the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of British Columbia.