Suffocated by the steel giant

Tony Buttaro’s battle for dignity in life and work

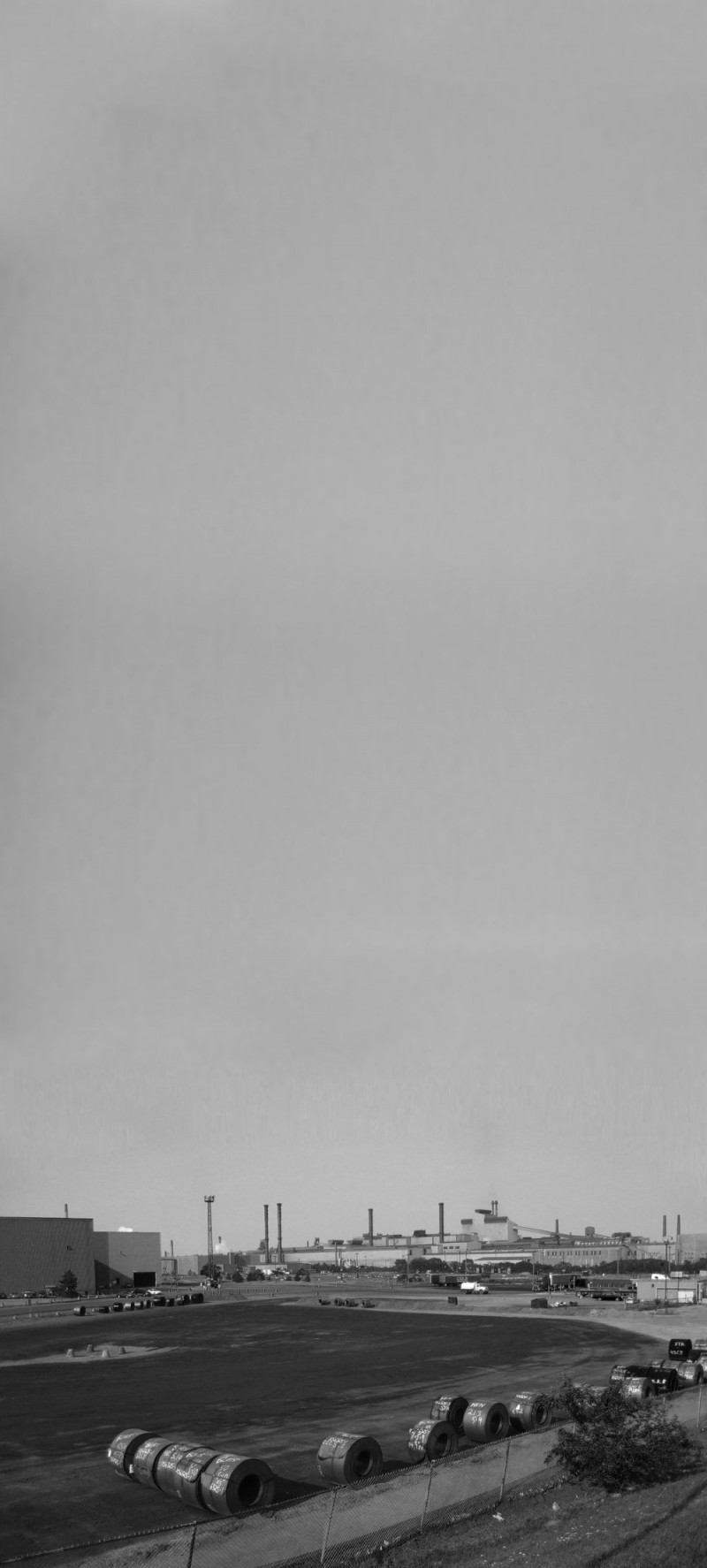

Dofasco, view from Burlington Street, Hamilton, Ontario. Photo by Rick Cordeiro.

Tony Buttaro is a Hamilton steelworker who injured his back at work. He later became a supervisor who had compassion for his workers. Tony paid dearly for these two things. He ended up physically and mentally traumatized. The retirement he had long dreamed about was destroyed.

In 1968, 21-year-old Tony started working in the foundry at Dofasco, a major steel producer, non-union. He was injured four years later when lifting a heavy steel plate. Tony recalls experiencing an “explosive” pain across his lower back and hip. He immediately hit the ground, unable to breathe. He was off work for a while. When he returned, the pain was still there. The pain was constant and unremitting: it plagued him all day, every day and is still with him 37 years later. Spinal movements became stiff and difficult. Further workplace recurrences added to that distress.

Some time after the injury, Tony was given modified work as a janitor in Dofasco’s cleaning services department. He was later promoted to supervisor, and then to Department Foreman. John Tompa, a cleaner who worked under him at the time, told me that Tony was a “people person,” saying “he treated everyone with respect and dignity.”

But that was Tony’s problem. In the mid-1990s, the steel giant was eliminating many of its injured workers. The methods included on-the-job harassment, increased workloads, pressure to take severance packages, and outright firings.

The company often pushed injured employees to come back to work early, before they had properly recovered.

All this went on despite provincial laws that required employers to accommodate their injured workers. Many employers viewed accommodation as something that cost too much.

When workers get injured make them wish they were dead

Tony was told by higher management to give disabled employees work beyond their capabilities. He was also told to apply stress techniques to break them. At one point, the company compiled what Tony described as a “hit list” of injured workers targeted for termination.

Tony could not go along with this. He told the higher-ups that these practices were unsafe and could cause injuries. Tony was then demoted to shift foreman. In February 1995 he was taken out of supervision entirely because of a dispute over Dave, a worker who died on the job. Dave had a heart condition that was vulnerable to stress. When he fell to the floor one day a co-worker tried to resuscitate him, a technique he was familiar with. Dofasco’s job trainer stopped him, saying they had to wait for the medical department. When the medical department arrived, however, Dave could no longer be revived.

Tony came upon the scene as Dave died. Seeing that threw him into an emotional turmoil from which he never recovered. He asked for an investigation. Instead, management told him to cool the workers, who were upset about the incident. Tony wouldn’t do it. He kept pressing for an inquiry, but he was told to drop the matter. He became depressed and started having panic attacks. He imagined that he was lying on the shop floor, with managers standing over him, laughing. He went off on stress leave. When Tony returned, he was told he was no longer in supervision. He was told that he was not a “team player,” and that he should have got over the death of Dave.

Getting the shaft

I met Tony in May 1995 when he had just gone off. He asked me to help him with the company, whom he feared was about to fire him. For the next fourteen years I represented him at the compensation board and appeals tribunal, the labour board, and the human rights commission. I came to admire his understanding, his integrity, his compassion for people, and his sense of humour.

At the labour board, Tony got a partial remedy that gave him some job security protection. He kept on working as an hourly employee, writing up job procedures. He joined an activist group of Dofasco injured workers who had been fired or treated unfairly, called SHAFT. Later, he was part of a plant committee that tried to unionize Dofasco, which was unsuccessful.

Unfortunately, Tony reinjured his back in October 1999 when a company bus he was on jolted up and down on a curb. “My life ended that morning,” he said. He described his pain as like a knife going into his hips, going up his back and taking his breath away. He doesn’t know where the pain will “fire next.” It shoots 24 hours a day, every day.

Tony also injured his neck and his left knee while at work. As a result of all these accidents, he can no longer do what he used to do. He stopped the things he had enjoyed, including working the backyard at home, going out on the lake in his boat, walking the dog, and cooking. And he could not sleep properly. He became morose and irritable. He started seeing a psychiatrist.

Tony’s life was dominated by pain and disability. He spent a lot of time seeing doctors and attending pain treatment clinics. He received regular nerve blocks. He underwent surgery to relieve the pressure on his neck.

All of this helped, but only a little. At work, the pain gradually worsened over the course of the shift. He had to get up and walk around every ten minutes. His concentration faltered. By noon “I was done.”

The Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB) had never recognized Tony’s 1972 back injury as a permanent impairment. It denied him a wage loss pension for it. It belittled his other injuries. We appealed, and these matters eventually ended up at the highest appeals tribunal. Called the Workplace Safety and Insurance Appeals Tribunal (WSIAT), it is inde pendent of the lower level WSIB. The hearings went on for many days, spread over a three-year span. Dofasco hired a major Toronto law firm, expert in compensation, to fight the appeal.

Tony testified at the hearings, as did co-workers. One of whom Dofasco disciplined for submitting documents that contradicted the information provided by the company.

Eventually, the parties reached a settlement through the mediation of the three-member appeals panel. Tony’s back injury was recognized, going back to 1972, including later recurrences. He was granted an ongoing 100 percent wage loss award. The neck injury was not recognized because an accident while traveling to treatment on company time was deemed to be non-compensable.

As a result of the decision, Tony received over $200,000 in arrears, tax free, as well as a full monthly pension. That allowed him to retire from Dofasco, which he did in September 2003, with a good ongoing income. He looked forward to relaxing, at last. Everyone rejoiced.

There was a fascinating moment on one of the hearing days. Two members of the compensation board’s governing body sat in to learn what went on at the appeals tribunal. At the first break in the morning, the business representative came over to me. He said he was shocked to learn what had happened to Tony. He said that this kind of thing should never come to the appeals tribunal. The WSIB should have straightened it out at the start. He vowed to ensure that this would never happen again.

Money isn’t everything

But that was not to be. A few months after the decision, the compensation board whacked Tony again. It took away the wage loss pension he had won at the tribunal, citing a minor technicality. That move was completely illegal. Lower bodies cannot override higher appeals decisions.

Tony was stunned, “kicked in the teeth,” as he put it. His long-sought retirement was suddenly taken away. He had repaid loans and made expenditures for his family based on the wage loss pension he was awarded. Now, with that regular income gone, he found himself in debt that he could not repay. Tony’s earlier exhilaration turned into a nightmare. He went into a long and dark depression.

I complained and complained about the illegality of what the compensation board had done, to no avail. We ended up again at the appeals tribunal -three years later. The tribunal was shocked by what had happened. It ruled that Tony’s full wage loss pension had to be restored.

The pension was then restored, but the damage was done. Tony was now a broken man. He sits in his room all day, in severe pain, sad, and ruminating about all these events.

As Tony thinks about the past, he re-experiences the despair, anxiety, and anguish he suffered at the time. He has post-traumatic stress disorder, with regular flashbacks and nightmares. He dreams that hit men from Dofasco are chasing him. In some dreams he and his friends are killed, with blood splattered all over. He often dreams that he is tied down in a prison within Dofasco’s melt shop. Managers put him into the oven, whereupon he wakes up screaming.

In other dreams, injured workers are taken to the oven where their bodies are melted down. Tony is forced to watch, as the managers taunt him and laugh at him. Out on the street, Tony is always on the lookout for company cars he thinks are spying on him.

Tony is a different person than the one I met years ago. He says he has lost interest in everything. He looks down; his bounce is gone. He says his retirement is a living hell. Though he left six years ago, the steel mill won’t leave him alone. These events torment him day and night.

Just this year, Tony started to improve with the help of a new psychologist. He wants to pursue compensation for traumatic mental stress. Despite everything Tony has been through, the fighter in him is still alive.

Unfortunately, Tony’s experience is not unique. Everywhere the ugly corporate-government machine continues to grind down injured workers. With the current recession, it is doing that more easily, and more often.

This article appeared in the September/October 2009 issue of Canadian Dimension .