Radical Winnipeg

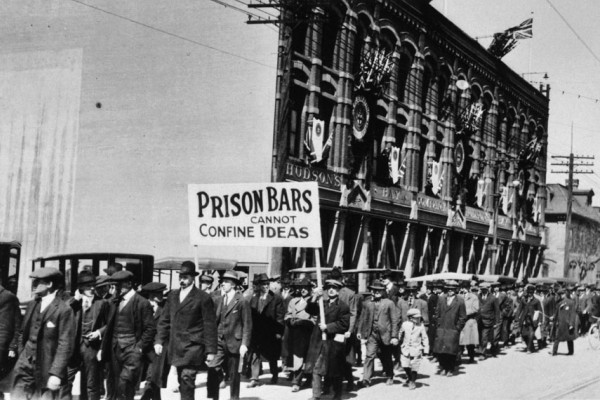

1919 Winnipeg General Strike. Winnipeg Tribune / University of Manitoba Archives.

As you cross the Slaw Rebchuck bridge, a cement arch straddling the vast rail yard that in earlier times cut off the city’s north from its south and center, a sign is visible. Opposite a high school named for a prominent organizer of the Winnipeg General Strike, on the sloped, brown roof of Nepon Motors, it reads “Welcome to the North End: People Before Profits.” Only an aspiration, I know – but where else but in Winnipeg would you find this welcoming?

Let’s take Winnipeg’s Radical Pulse Winnipeg – home to Canadian Dimension magazine and Alert Radio and to Mondragon Coffee House and Book Store – all located in the Emma Goldman Grassroots Centre building at 91 Albert Street in Winnipeg’s historic Exchange district. Winnipeg – home to the Winnipeg Labour Choir, the Nellie McClung Theatre group, Plug-In Gallery, Thunderbird House and the Indigenous Peoples solidarity movement, Propaghandi the punk rock band, the Urban Shaman Gallery, the Structured Movement Against Capitalism, CHO!CES, CCPA-MBA, Canada Palestine Support Network, Independent Jewish Voices, Winnipeg Peace Alliance, The Assiniboine Credit Union, May Works, Grassroots Women, the Winnipeg Folk Festival, and Arbeiter Ring Publishing House. Winnipeg – the one city in the country where the NDP is all but hegemonic.

That’s today – not too shabby by current standards – but Winnipeg’s reputation as a hotbed of radical politics and labour activism really goes back to the time of the Winnipeg General strike and even before that.

Wave after wave of immigrants landed in Winnipeg, a significant minority of whom had been dissidents and revolutionaries in their home countries. They carried their socialist or anarchist ideas and their class struggles with them across the ocean. They formed trade and farmers’ unions to protect their interests, engaged in strikes, formed cooperatives and mutual aid societies, and even established their own schools and newspapers-partly.

In 1907, for example, Jewish radicals formed their own Arbeiter Ring (“Workers’ Circle”) local in Winnipeg, a mutual aid society that had as its ultimate goal the abolition of capitalism, and its replacement by some kind of “socialist” society. That very year this element of Winnipeg’s radical community invited Emma Goldman – the most famous anarchist in North America – to speak. J. Edgar Hoover called her “the most dangerous woman in America.” Red Emma visited and lectured in Winnipeg on several other occasions, the last one in late-1939, just five months before her death.

Radical Jewish groups established not one but five different and competing Yiddish schools between 1912 and 1963. The Peretz Folk School, named after the renowned Yiddish writer I. L. Peretz, served as a social, cultural, and educational centre with the struggles for social justice pervading its activities both inside and outside the classroom. The Labour Zionists responded with the Jewish Folk Shule; the communists with the Liberty Temple School, later to become the Sholom Aleichem school; and the Arbeiter Ring with its own school.

The anthem of all the schools was “The Internationale” with its rousing chorus:

Arise, ye prisoners of starvation,

Arise, ye wretched of the earth,

For justice thunders condemnation,

A new world is in birth!

As related by Winnipeg Jewish historian Harry Gutkin, the “Internationale” was “sung with gusto, alike by the tailor who worked in a needle trade factory and the railway worker employed in the CPR shops, and perhaps with somewhat less enthusiasm by the owner of a large bedding factory … who stood alongside of those engaged in real estate enterprises …But they all stood at attention alongside of the students when the “Internationale” was sung on special occasions.”

The Winnipeg-based Federation of Ukrainian Social Democrats was established in 1909, affiliated with the Social Democratic Party of Canada the following year, and in 1914 became the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party. By 1917 it had become Marxist, and a year later it was pro-Bolshevik, with two thousand members.

With voluntary labour, the Ukrainian Labour Temple Association (ULTA) built the Ukrainian Labour Temple in 1918, first of its kind in North America. This magnificent structure still stands. As originally designed it contained an auditorium, print shop, and offices, as well as classroom and library space. The hall’s main floor and balcony capacity held up to a thousand people. The hall quickly became a center of trade unionism and socialist politics and housed theatrical, choral and dance groups. The country’s first Ukrainian newspaper, Robochy Narod (Working People), was published from this location. The ULTA spread its political influence throughout Manitoba, sponsoring branches and establishing the Workers’ Benevolent Association, a fraternal insurance society still in existence. Ukrainian socialists also built the People’s Cooperative, originating as a coal and wood cooperative in 1928 and then moving to dairy products, the Co-op only ceased operation in 1992.

The Communist Party, among its other activities, established the Progressive Arts Club in several centres across the country including Winnipeg. Set up in 1931, its Winnipeg branch had a sketch group, a drama group, and a writer’s group. With Joe Zuken as director the drama group launched a production of “Eight Men Speak” about leaders of the Community Party who had been charged with sedition and were sitting in Toronto jails. The Club booked the Walker Theatre, but it was locked out when Winnipeg’s city fathers threatened to revoke the theatre’s license if it allowed this play to be performed.

The single event that launched Winnipeg’s reputation as the most radical city in Canada was of course the Winnipeg General Strike. The General Strike began in May 1919 when all the unions in the city voted to support striking building and metal trades workers in a confrontation with their employers. The strike lasted six full weeks and it spread like wild fire as non-unionized workers joined the walkout.

Winnipeg was paralyzed. Through its strike committee the workers were effectively running the city. Scholars of the strike have counted 171 mass meetings taking place over its course, an unprecedented exercise of democratic participation in civic affairs. These were radical times. The Winnipeg General Strike occurred alongside organized workers revolts from Seattle to Berlin in the year that saw the first Socialist Revolution. In Winnipeg, six months before the strike, seventeen hundred workers – Anglo, Ukranian, Jewish, Polish, and others – crammed the palatial Walker theatre to hear speaker after speaker denounce the Canadian state, proclaim their support for the Russian Revolution and hail the working class. At the Western Labour Conference held in Calgary just two months before the General Strike delegates voted to organize general strikes against the imperialist attack on the Russian Revolution and in favour of the six hour day, and to begin the process of forming a separate revolutionary union movement, the One Big Union. The Winnipeg Trades and Labour Council had sent as its delegates R.B. Russell and R.J. Johns, prominent members of the Socialist Party of Canada. Both were soon to play leadership roles in the General Strike, although they and other leaders maintained that the strike had no agenda other than collective bargaining rights and a living wage.

Given the extraordinary circumstances surrounding the strike and the fact that workers were now running the city, the state read it differently. This was an insurrection. Acting accordingly, they arrested strike leaders or deported them.

And they smashed the strike.

In its aftermath many socialist and labour activists were nudged toward electoral politics. The Independent Labour Party made an important electoral breakthrough in 1920 as eleven of their candidates, some from jail, were elected to the Manitoba Legislature. Two Labour representatives, J.S. Woodsworth, and A.A. Heaps were elected to Ottawa a year later. The ILP was eventually superseded by the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation which, in turn, gave way to the New Democratic Party. Other strike activists, drawn mainly from the immigrant working class, joined the newly formed Communist Party of Canada.

Though radical politics never disappeared from Winnipeg, it would never again play such a dominant role –here or anywhere else. For a very short moment, all the divisions within the labour force that so weakens the capacity of the working class to mobilize its forces to exercise economic and political power – gender, race, ethnicity, skill, occupation, and beliefs – magically disappeared. Angered by a fumbling and corrupt capitalist class and its political representatives, inspired by what they heard of the revolution abroad, and confident in the emerging new generation of working class and socialist leaders, the working class in all of its diversity found a way to pull together and forcefully. Once that moment passed, the divisions reimposed themselves. The working class lost its sense of purpose and its confidence while the capitalist class recovered its leadership position.

To be sure, special moments returned – during the industrial union drive in the 1930s, the anti war and Canadian independence movements of the sixties, the anti-free trade movement of the eighties and the anti globalization movement of the nineties. But so far they have not posed the kind of challenge mounted against the capitalist order as occurred around the time of the Winnipeg General Strike.

What will emerge out of today’s financial and economic crisis and the far more dangerous climate crisis? It is too early to tell. It’s clear that only a fundamental change in the way we do politics and structure our economy can shift us onto a path that is at once sustainable and equitable. Objectively speaking, this period should give rise to a very long and explosive moment of radical thought and organizing. Heeding Marx’s dictum though – “the point is finding once more the spirit of revolution, not ofmaking its ghost walk about again” – we need to recapture the spirit of 1919 while building a politics of our own time.

We can say this. Radical Winnipeg today is not to be found in union halls, at NDP gatherings or at the Selkirk Avenue headquarters of what remains of the Communist Party. More likely it’s to be found in places like the Defenders of the Land gathering we had here last fall which sparked the Indigenous sovereignty weeks across Canada, and may prove a historical milestone. How appropriate in the province created by the Riel Rebellion! As we think about how to recapture the spirit of 1919 while building a politics of our own time one critical feature will be mobilizing Aboriginal dissent as an integral part of the overall anti-capitalist movement.

Cy Gonick is the founding editor of Canadian Dimension.

This article appeared in the January/February 2010 issue of Canadian Dimension (Our Winnipeg).