Media as Insurgent Art

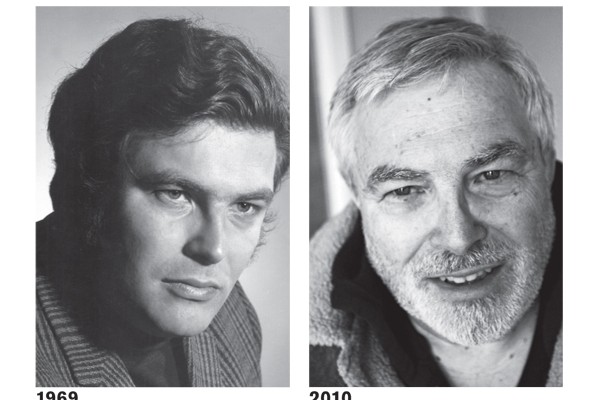

Benicio Del Toro as Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara

Of Pirates, Pixels, and Politics

In the May issue of Wired Magazine, writer Kevin Kelly argues that the global dispersal of free information and the mushrooming world of open-source software constitutes a New-Socialism. This “global collectivist society,” he claims, “is socialism without the state. This new brand of socialism currently operates in the realm of culture and economics, rather than government – for now.” While it’s easy to scoff at Kelly’s claims – socialism still asks who owns production – it is indisputable that revolutions in communication and technological tissue are quickly redefining the space and sites of global protest.

While Twitter and Facebook were a definite boon for Iranian protestors, this technology has a dark side. Despite Kelly’s assertions of cyber-people’s power, tech-empires are still in the hands of the privileged few. The Wall Street Journal reported that European telecommunications companies Siemens AG and Nokia helped the Iranian government develop one of the world’s most sophisticated mechanisms to monitor and control communications on the internet. Media reform group Free Press warns the same technology was widely used by the Bush administration in their domestic surveillance program and is widely used to round up dissident bloggers in China.

In the election aftermath, Iranian solidarity flooded Twitter and Facebook with pro-Moussavi green profile pages and activists spamming Iranian censors with synchronized subversive messages. But support also came from an unlikely source: pirates. File sharing swashbucklers ThePirateBay.com launched an online network in support of Iranian election critics allowing users to dodge the regime’s censors. Their site, iran.whyweprotest.net, allows “a secure and reliable way of communication for Iranians and friends” and directs users to an anonymity system, which can be used to hide their internet locations. “Even if a ballot is silenced, the voice behind it cannot be,” the site said.

But is there is a danger in placing the medium before the message? Is Iran’s political upheaval thanks to a “Twitter revolution” or old-school political consciousness? In 1944 German sociologists Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer argued “the basis on which technology acquires power over society is the power of those whose economic hold over society is greatest. A technological rationale is the rationale of domination itself. It is the coercive nature of society alienated from itself.”

Are Facebook and Twitter responsible for de-politicizing struggles into online quarrels instead of real shows of political power? Adorno and Horkeimer were writing at a time when media gatekeepers were the Ayatollahs of information. Their analysis that “the producers are expert” still applies to monopoly media empires and their talking heads. But with Web 2.0, production has changed hands. Individuals and collectives are not only creating content, they are seizing productive methods by creating their own software and daring to share it. If this is a form of socialism, then we are missing a valuable opportunity if we don’t fully engage with it and shape it toward real political goals.

Soderbergh’s Che: Homeland or Boredom

Directed by Steven Soderbergh

Starring Benicio Del Toro

I had high hopes for this film. Not just because I thought it would be the Oceans 11 of revolutionary cinema, but because it would be a nice follow-up to the beautiful Che biopic The Motorcycle Diaries. What Che parts 1&2 lacks in cinematic creativity and political context it makes up for in detailed historical accuracy – although at 4.5 hours it’s detail et nausea. Part one takes us back to 1959 Cuba and the revolutionary war waged from the Sierra Maestra. The seizing of towns and villages; the distribution of land amongst the peasantry; and Che’s revolutionary discipline make part one an enjoyable overview of the struggles of urban guerrilla warfare and muddy comradely heroism. Che’s myriad roles as doctor, instructor, and soldier are interspersed with a flash-forward to his legendary 1964 UN speech. Unfortunately, this is the only creative use of cinematography in the film, and it is only in these sparse frames that we learn of Che’s anti-imperialism and world-view.

After taking Havana – and a fifteen-minute intermission for the audience – a disguised Che takes off for Bolivia. Is he trying to remake a Cuban style revolution there? Is he acting as an agent of Soviet expansionism? Why doesn’t he have support of the Bolivian Communist Party? None of these questions are fully addressed and we’re left wandering with a bag of vagabonds through the Bolivian bush. I won’t bother with any more plot-details, but suffice it to say Che’s tragic end is made worse by a half-hour scene detailing every bullet fired and every grunt emitted. Ultimately this film fell flat artistically and politically. I despise Che-worship, and this film only reinforces it by skipping over the political, emotional, family man Che and framing him as a heroic, scraggly, guerrilla god. The film exists in a political context where Che is a commodity and his ideas are considered laughable by most. What we need to take from Che isn’t the “inspiration” or “revolution” peddled by liberal-hippies, but the need to once again engage with dangerous ideas.

This article appeared in the September/October 2009 issue of Canadian Dimension .