Canada’s democratic deficit can no longer be ignored

Declining trust, economic inequality, and institutional failures have left the door open to reactionary anti-system politics

Parliament Hill, Ottawa. Photo by Bill Badzo/Flickr.

Politics in the United Kingdom has been upended by the rise of a right-wing populist force that now stands as a serious contender for power. From our two overlapping yet distinct perspectives—a political science professor who studies parties and elections and an independent journalist seeking to hold politicians to account—we recognize many of the same currents propelling the UK’s populist insurgency at work here in Canada as well.

This is largely a result of the failures of the political establishment to grasp and address our deepening democratic deficit. Canada faces many of the same problems, and those in power appear equally asleep at the wheel.

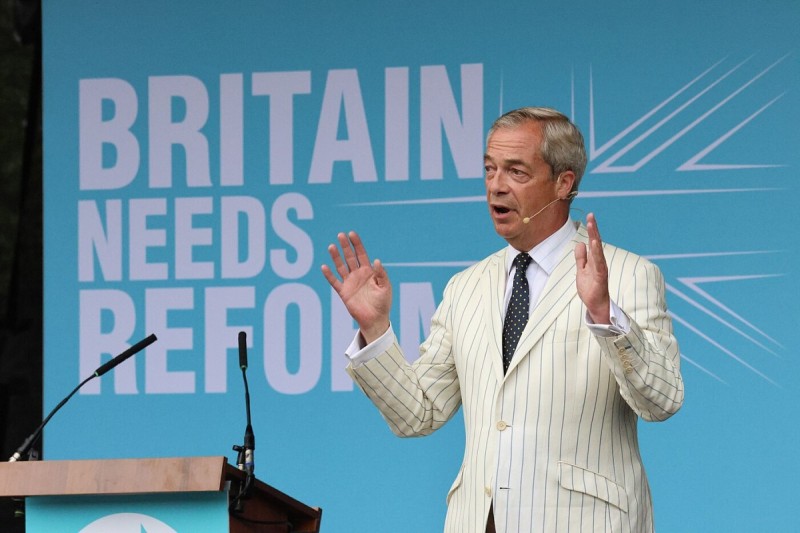

We recently caught a glimpse at what might lie ahead for Canada. Reform UK, the right-wing populist party helmed by Nigel Farage, held its annual conference on September 5 and 6 in Birmingham’s National Exhibition Arena. This was a conference of a party ready for power, flush with close to 250,000 members and sitting pretty at the top of opinion polls. If they can maintain it, Reform’s current share of stated voter intention places Farage’s outfit in pole position to form government, based on a recent projection by YouGov.

The Reform faithful who packed the convention floor may have been surprised that a guest of honour from Canada was on the agenda. Preston Manning, founder of the namesake Reform Party of Canada, was given prime podium time on the Friday evening of the conference to bestow his blessing upon Farage’s movement.

Manning’s career in federal politics, and the rise of Canada’s Reform Party in general, is typically understood today to be a defining episode in the now generations-old matter of “western alienation.” Indeed, the party was founded in 1987 by interest groups and activists estranged from the Montréal-Ottawa-Toronto axis of political and cultural power in Canada. “The West Want In,” went the famous rallying cry.

Yet “The West” meant more than simply a geographical region and its concomitant economic interests. It signalled the populist style of politics that has deep historical and cultural roots in Canada, from the Prairies to the Pacific Ocean. Just think of the United Farmers, the Progressives, the CCF, and Social Credit.

This populist politics was a critical component of Reform’s appeal. It turns on a pervasive critique of the failures of the eastern establishment—that is, the “elites,” or Canada’s two “natural” governing parties—to build meaningfully democratic institutions that live up to its self-professed standards of representation, responsiveness, accountability, and transparency.

Manning’s populist ideological orientation was an important driver of the party’s move from fringe regionalist outsiders in 1987 to strong electoral performances in 1993 and 1997. The Reform Party tapped into the raw appeal of proposals to rectify blatant democratic deficiencies during its rise in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The party’s manifesto from 1992 highlights a range of policies that address perceived gaps in the democratic character of Canada.

Entitled 56 Reasons Why You Should Support the Reform Party of Canada, the manifesto has plenty of talking points and policies derived from social conservatism and western alienation that remain familiar to politicos today. It also, however, contains a series of robust proposals to meaningfully reform the institutions of democracy in Canada to address failures in government responsiveness and representation. Proposals for a Triple-E (equal, effective and elected) Senate, more referendums and citizens initiatives, a commitment to combat and root out patronage, and institutional changes to decrease stifling party discipline in Parliament all strike at major areas of democratic and representative deficiency that linger still in Canadian democracy.

As the 1990s dragged along, much of this democratic reform agenda was dropped by Manning as Reform hunted for votes east of Manitoba. It is, though, worth underscoring how important this frontloaded critique of the failures of Canadian democracy to live up to its billing was in Reform’s rise.

The UK’s Farage invokes Manning’s legacy in this guise and makes no bones about how Reform UK was explicitly named after its Canadian cousin. Farage regularly touts what he calls the “reverse-takeover” of the Progressive Conservative Party by Reform that created the modern Conservative Party of Canada as an inspiration for his long-term goal of consolidating the British right under his banner.

Farage’s rhetoric today appeals to a groundswell of belief that a once great democracy is increasingly a rigged game and defective in its capacity to deliver the basics of modern governance and effectively respond to the needs of its citizens. Combined with the promise of the quasi-fascist MAGA-esque approach to immigration, it is proving a seriously effective political recipe.

Nigel Farage campaigning for Reform UK during the 2024 general election. Photo by Owain Davies.

Canada was set for a similar course not long ago. Before the exogenous shock of President Trump’s annexation threats threw Canadian (and world) politics on its head, Canadian Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre’s message of “Canada is broken” hit a seriously resonant note across the country and a majority government beckoned.

Political scientists have long understood that mutual trust amongst the population and trust in governing institutions is vital for the maintenance of a healthy democratic culture. These attributes are in decline in Canada, not as sharply as in other democracies around the world, but complacency in an era of democratic recession is not an option.

The precipitous decline in fortunes of the UK Labour government is directly tethered to the damp managerial centrism of Prime Minister Keir Starmer, who is either unable or unwilling to profess his guiding vision of politics. His fellow technocrat, Mark Carney, has a somewhat warmer touch, but has drifted considerably from the agenda that he used to pull the Liberal Party out of an electoral grave at the end of April. Carney’s apparent interest to govern like a CEO could well exacerbate the perception of democratic deficit across the country.

But, as in the UK, Canadians’ faith in democracy is not wavering without solid basis in reality.

Income inequality is at an all-time high and the economic landscape remains dominated by a few concentrated oligopolies. Our electoral system grants strong majority governments to parties that receive a slim plurality of a diminishing turnout of the popular vote. Justin Trudeau’s 2019 and 2021 minority governments were both formed out of the record lowest popular vote shares in Canadian electoral history. As GenSqueeze puts it, Canada is addicted to “high and rising home values” that render shelter a speculative investment rather than secure lodging. A temporary foreign worker program described by the United Nations as “breeding ground for contemporary forms of slavery” has contributed to a multi-generational consensus on the benefits of immigration to wither. Liberal governments have relied on section 107 of the Labour Code to curtail the right to strike, sowing distrust in the domain of industrial relations.

Consider, too, that 40 percent of MPs in the previous federal Parliament were landlords—defined by a disclosure that they receive rental income every month. There is nothing untoward about that in and of itself, of course, but in a time of acute housing crisis it contributes to the perception of a descent into an almost feudal system.

Canadians might also be forgiven for questioning the motivations of their representatives, when loopholes make it possible to get around ethics and conflict of interest requirements. Even where such loopholes don’t exist, obligations are not consistently being met. For example, despite the federal election taking place on April 28, as of early October, there is still no update on the conflict-of-interest disclosures in the government. There is a 60-day window in which they are legally required to submit their disclosures, so we should have seen them by June 27. This kind of lax attitude to ethical obligations is common in governments across the country, with Newfoundland and Labrador lagging in last place.

As for the nation’s finances, the Parliamentary Budget Officer is sounding the alarm around the growing budgetary deficit. Those who are not deficit hawks may not necessarily be troubled, except that this taxpayer money is not allocated to fix crumbling social services but is instead inflating private corporations amid dubious corporate welfare and industrial policy schemes.

More than 40 percent of the country is living paycheque to paycheque, barely able to afford their rent and groceries. Thirty-eight percent of Canadians are afraid that they will lose their job within the next year.

Even the institutions that have traditionally pushed back against such government failure continue to atrophy, with media across the country being consolidated and journalists being culled from media rooms, leaving the fourth estate a diminishing force in its traditional watchdog role.

The rise of Reform UK is a warning to the political establishment that voters will rush toward anti-system politics when their democracies over-promise and under-deliver. As Canada’s Reform Party agenda from more than 30 years ago demonstrates, the deficiencies listed above are clearly the result of decades of neglecting to nourish and sustain the democratic character of our institutions.

Canada appeared headed for a Poilievre-led populist backlash until the political snow globe was shaken by Trump. It’s hard to imagine Carney’s Liberals collapsing as completely as the hapless and rudderless Starmer-led Labour government in the UK. Still, the rise of hard-edged, anti-system populism in Canada will be difficult to avoid unless the centre and left confront the widening cracks in our democracy before further economic turbulence fans the flames.

Dónal Gill is a political science professor at Dawson College and Concordia University.

Isaac Peltz is an independent journalist whose work can be found at On the Trail.