What Happened in British Columbia?

The events that rocked British Columbia in late April and early May were both stunning and, sadly, almost predictable. Many progressive activists had forecast that a major labour confrontation with the hardline Campbell Liberal government would break out sooner or later. What few foresaw was the excitement in the streets as thousands of people rallied to back 40,000 health care strikers, and the euphoria as unions across the province geared up to walk off the job in solidarity.

Then, a last-minute memorandum of agreement ended the one-week strike with some minor adjustments to the enormous rollbacks demanded by the employers. The deal shocked the mass movement which had emerged, renewing the debate over the tactics and strategies of labour leadership in the province.

Both the Hospital Employees’ Union and the BC Federation of Labour called the May 2 memorandum of agreement a “victory,” tempering this assessment by stressing that it was the best that could be achieved under difficult circumstances. But the outcome has been discussed for weeks, in HEU locals, labour councils, public forums, and progressive websites. Even the HEU’s own executive was divided at a May 3 meeting which endorsed the memorandum by a vote of 13-7.

Since its election in May 2001, the Campbell government has repeatedly tried to break unions, ripping up collective agreements on a number of occasions. After the courts struck down provisions of Campbell’s Bill 19, which stripped class size limits in BC Teachers’ Federation contracts, the Liberals simply re-wrote the law, stating that their bill applies “despite any decision of a court to the contrary.”

This time, the Liberals imposed a contract so offensive that the public was appalled. Bill 37 was rammed through on April 29, four days after the strike began. The Bill included a 15% clawback in wages and benefits, retroactive to April 1; an increase in the work week from 36 hours to 37.5; cuts to overtime by up to two hours per day at the employers’ whim; cuts to seniority rights and access of part-timers to extra hours, and no job security for the two-year duration of the contract.

Thousands of British Columbians quickly joined the picket lines at over 300 job locations. The struggle was a major theme at Vancouver’s first major labour-backed May Day rally in many years, drawing some 10,000 people. Over 25,000 CUPE members walked out on April 30, and a number of unions prepared for escalating job actions. On Monday, May 3, schools, government offices, public transit in the Lower Mainland and Victoria, and the ferry system would have shut down. There was growing potential for walkouts by the coastal IWA locals, longshoremen, and other private sector workers.

Ever since the Campbell Liberals announced huge cuts in services and jobs in January 2002, labour and community activists have advocated such militant tactics as the best way to halt the right-wing offensive. But the BC Federation leadership was clearly divided over whether to ratchet up mass pressure on the Liberals, with the IWA seen as the most prominent union opposing such a strategy. May 2002 saw the last large-scale protest mounted by the labour movement, although local labour-community coalitions in some smaller cities and towns organized several effective actions.

At the November 2002 BC Federation of Labour convention, there were demands to launch a more effective fightback. An Action Plan was adopted, instructing the Fed executive to begin organizing a wide range of protests, up to and including work stoppages if necessary. But the Action Plan simply gathered dust. Individual unions were left to resist the Liberals as best they could, without the coordinated backing of the entire labour movement. The HEU leadership reached a tentative agreement with the province, cutting wages in return for guarantees of no more contracting out. That deal went out the window when it was rejected by a membership vote in the spring of 2003.

The fightback began to shift into reverse when a major IWA local hatched a plan with the government and transnational corporations to move into the health care sector. Deals were cut to contract out hospital food and laundry services, with the affected workers pushed into the IWA. Wages were slashed by as much as 40-50%, and other contract benefits gutted. This blatant class collaborationist raid on a union facing a vicious assault by the Campbell government shattered any illusion of unity in the BC Fed, but the Canadian Labour Congress did not take any meaningful action against the IWA until early in 2004.

The November 2003 BC Fed convention, meanwhile, re-confirmed the Action Plan. By this time, everyone knew that the hospital workers were fighting for their union’s life, with their contract expiring in a few months and their jobs being wiped out. CUPE announced plans for a “Democracy Day” walkout, and tried to convince other unions to take part. Unfortunately, little progress was made as the weeks went by and the HEU contract neared its expiry.

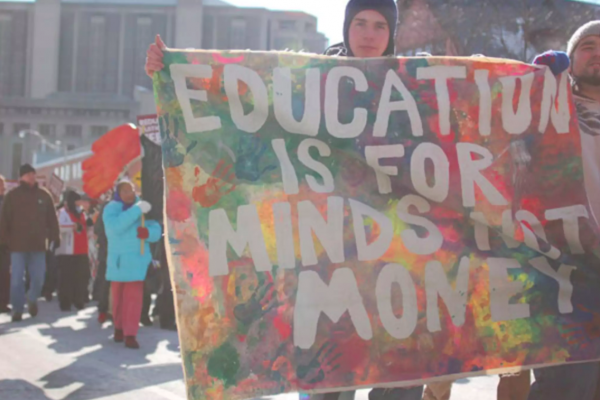

Against this background, there was a spontaneous flowering of support when the healthcare workers’ picket lines went up. Instead of walking out for a day, as the union had announced, it launched a full-scale strike, hoping to catch the employers off-guard. Opinion surveys revealed strong support for the workers, and deep anger against the Campbell Liberals, whose cuts are widely seen as responsible for declining health care and education. Since most HEU members are women, including a very high percentage of people of colour, there was a strong sense that walking the picket lines was one way to resist a sexist, racist assault on workers who are trashed in the media as “overpaid”.

After the Liberals had rammed back-to-work legislation through, grassroots sentiment moved towards province-wide walkouts. Union leaderships scrambled to put together a coordinated plan for mounting strikes. A copy of the proposal somehow fell into the hands of the corporate media, which tended to ascribe more long-term planning than was actually the case. There was a mood of euphoria in the air, a sense that maybe the hated, arrogant Liberals could finally be forced to retreat.

But at the same time, the BC Federation of Labour was mainly focused on negotiations with the government over the May 1-2 weekend. News emerged early in the evening of May 2 that a deal was near. Most hospital picket lines came down within hours.

The leadership’s argument was that inconvenience to patients and the general public would erode support for the strike, making it harder to pressure the government. This strike, they pointed out, was not meant to challenge the government, but only to win better terms for the hospital workers.

Yet the BC Federation leadership had said their goal was indeed to force the government to back down on the main terms of the imposed contract. The May 2 memorandum did not reduce the 15% clawback - it simply delayed it to May 1 rather than April 1. Contracting out was capped at 600 FTEs over the next two years, but the government may have other legislative loopholes to evade this provision. The government did agree to provide $25 million for an enhanced severance package, but the total losses to workers run into the hundreds of millions of dollars.

Many strikers and their supporters believe that the May 2 memorandum fell far short of the minimum needed to call off the strike. Arguments over the motives and tactical estimations of those who cut the deal will probably continue as long as the debates over the fate of Operation Solidarity in 1983.

But given the tendency of the BC labour movement leadership to count on an NDP victory in May 2005, electoral strategy may have played a key role in these events. While the Liberals feared that province-wide strikes might damage their re-election chances, the NDP and its allies in the BC Fed were equally worried that the government could use an “us vs. union chaos” campaign to undermine growing support for NDP leader Carole James.

We’ll never know how matters would have played out if the deal had not been reached on May 2. But there is a strong feeling in the ranks of the labour movement that this decision squandered a golden opportunity. There will probably not be another occasion before BC’s May 2005 provincial election to build such powerful solidarity in the streets against the right-wing agenda tearing apart this province. And it’s certain that the way the memorandum was reached will increase mistrust between labour and its potential community partners, and within the trade union movement itself.

The good news is that the Campbell Liberals stand exposed more than ever as a brutal gang of pro-corporate thugs. Right across Canada (especially in Québec) workers and their allies are increasingly in a mood to stand against this right-wing assault. The challenge in BC will be to build a stronger union leadership, committed to class struggle instead of hoping that a new NDP government can solve all problems. And that won’t be easy.

Kimball Cariou is editor of the People’s Voice and a member of the CD editorial collective

This article appeared in the July/August 2004 issue of Canadian Dimension .