Tear down that statue!

Rethinking our history will mean bringing down the symbols of oppression that represent past wrongs and underwrite current ones

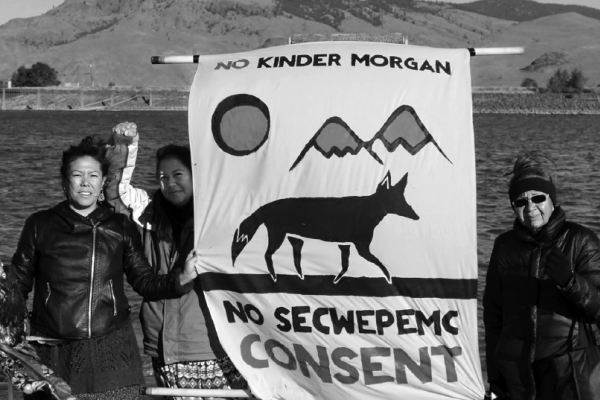

On the night of June 6, demonstrators tore down the statue of Egerton Ryerson that stands outside the Toronto university named after him. Watching the statue fall, writes David Moscrop, one could see a small but notable act of accountability. Image by Canadian Dimension.

On Sunday night, demonstrators tore down the statue of Egerton Ryerson that stands outside the Toronto university named after him. Ryerson was a racist who helped build Canada’s residential school system and thus took part in the genocide of Indigenous peoples. Watching the statue fall, one could see a small but notable act of accountability. Here’s to many more.

In early June, Guardian columnist Gary Younge argued “Statues of historical figures are lazy, ugly, and distort history… Let’s get rid of them all.” He wrote of a British “peculiar fixation with statues,” casting them as an attempt to “petrify historical discourse, lather it in cement, hoist it high and insist on it as a permanent statement of fact, culture, truth and tradition that can never be questioned, touched, removed or recast.”

The petrification is dangerous because it is permanent, or semi-permanent at least, and while some may claim monuments as history, Younge argues “This statue obsession mistakes adulation for history, history for heritage and heritage for memory. It attempts to detach the past from the present, the present from morality, and morality from responsibility. In short, it attempts to set our understanding of what has happened in stone, beyond interpretation, investigation or critique.”

The setting in stone of history not only distorts the past, but supports contemporary systems of oppression that benefit some at the cost of others. National myths excuse past transgressions and help cloak present misdeeds in the language of “it’s complicated” and “that’s who we were, but this is who we are now.” History becomes either invidious comparison according to defenders of orthodoxy or else a measuring stick by which we compare our “progress.” How then to account for the legacies of oppression that continue to marginalize by way of contemporary institutions? Well, “these things take time.” Please.

At the same time Younge was writing his column, the toppled statue of slave trader Edward Colston, which was torn down last year in Bristol by Black Lives Matter protestors and dumped into the harbour, was put on display. It bears the graffiti from protestors and lies on its back. And it now speaks to history, defaced and placed in context, far more than it ever has.

The toppling of Colton’s statue was a rallying cry and a moment of catharsis. In Canada, we are entering a period of reckoning. We must and will face our historic and present realities of colonialism, racism, sexism, ableism, xenophobia, and homophobia. Grappling with what has been done and continues to be done to marginalized individuals and communities—particularly Indigenous peoples—will entail symbolic as well as material accountability. Statues will come down. Streets and buildings and institutions will be renamed. Resources and lands will be returned and redistributed. History will be rewritten to account for buried fact, adjusting received wisdom and thus truth. Count on it.

There are no downsides to the teardowns and renamings, aside from cost, which is negligible and ought to be borne by those who’ve benefited from structures of oppression. We won’t forget these figures. Our aesthetics will be none the worse for it—indeed, as Younge and others have argued, they’ll be better. What’s more, the argument for tearing down statues and renaming streets, buildings, and institutions to loosen up the iron grip that orthodoxy has on our history is compelling. Alongside it, we ought to also embrace another imperative: the creation of more inclusive public spaces.

No one ought to have to walk past a statue of a figure who was complicit in the oppression or exploitation of a group to which they belong. Public spaces are meant for each one of us. They are increasingly rare as private fiefdoms encroach on what we hold in common—as they intrude into the shrinking spaces where we can gather together without being expected to act as units of consumption. Public spaces ought to be welcoming, accessible, and inclusive. Public spaces certainly should not venerate those who have committed heinous acts.

If the movement to hold past figures accountable seems extreme, that’s because our bias towards power (typically white and male) has tilted so far beyond reason that even a small adjustment towards justice and inclusion seems extraordinary. Understanding present struggles for justice and accountability requires us to put history in context. A rough but imperfect analogy might help.

Say some ancestor of yours stole $100 from another person and passed it down through the generations, interest accruing, until it reached you. Say your share of the legacy was $500. If someone were to take half of it from you, it might seem to you deeply unfair. But the morally correct conclusion would be that you had no right to it in the first place: you haven’t earned it, the gain was based on a crime, and quite frankly, you’re getting a bargain being able to keep anything at all.

Canada is a morally illegitimate state. It is legally legitimate within the domestic and global laws that legitimized states after the fact, but that legitimacy is tautological. The global state system is based on the ex post facto recognition of expressions of power—especially colonial power. Colonizers committed crimes, built states on those crimes, then decreed that it was proper, right, and even good that they’d done so.

If the claim that Canada is illegitimate strikes you as a bit much, go back through the history of the country and ask yourself some basic questions. For instance, would a state founded on manipulation, dispossession, and genocide be legitimate? If your answer is no, then ask yourself at what point did Canada (which is founded on both by way of British and French colonialism) become legitimate? The answer, morally, is never. If you answer yes, then you accept that power, even great crimes, is the basis of legitimacy, including states. If that’s the case, then at the very least you must accept that even violent resistance to the Canadian state would be appropriate now. That would include toppling statues and doing whatever it takes to rename schools, buildings, and institutions.

We are in the midst of a tectonic shift. History is a funny thing, since you often don’t realize you’re living it, until you do. Sometimes, things don’t change, then sometimes they change drastically and immediately and you’re left wondering how things were ever otherwise. There’s a quotation attributed to Lenin which reads, “There are decades when nothing happens, and there are weeks when decades happen.” But the truth is that while it may seem, to those who do not pay attention, that nothing happens and then suddenly everything happens, as if from nowhere, structural shifts are the product of labour, emotional and physical. Change may seem to come about as if from heaven, yet it is the work of individuals who put their time, resources, bodies, and even lives on the line that brings about shifts in how we think, talk, behave, legislate, and so forth.

Today, things are changing as marginalized groups are more and more successful in their fight for rights, recognition and justice. There is and will continue to be a backlash against them and their work, but the struggle continues. That work will include rethinking our history and tearing down the symbols of oppression and orthodoxy that represent, even glorify, past wrongs and underwrite current ones. Those who find themselves unsure of which side they wish to join ought to think long and hard about what they stand for. They ought to consider what they’ve been taught—and what they may have not been taught. They ought to take time to learn about communities who demand more from the state, its institutions, and all of us. Then they should join with those communities and tear down the statues!

David Moscrop is a contributing columnist for the Washington Post and the author of Too Dumb for Democracy? Why We Make Bad Political Decisions and How We Can Make Better Ones. He is a political commentator for television, radio, and print media. He is also the host of Open To Debate, a current affairs podcast. He holds a PhD in political science from the University of British Columbia.