A decolonized society

We need a society based on human solidarity that rejects colonialism and cherishes Indigenous rights and sovereignty

Blockade at 1492 Land Back Lane in Caledonia, Ontario. Photo courtesy of One Dish One Mic.

About a year ago, I chanced upon a remarkable piece of Indigenous history right where I live in the Toronto suburb of Scarborough. It’s a burial mound for some 523 people and the skeletal remains within it were laid out according to the requirements of the Wendat Feast of Souls sometime in the 14th century. This was perhaps 300 years before the first Europeans appeared in the area.

Despite the sense of wonder I felt at what I had come across, I couldn’t help but be appalled by the arrogant racist disrespect with which this find has been treated. As I wrote at the time, the burial site on “Indian Mound Crescent” is marked with a clumsy and inaccurate plaque and is otherwise almost totally ignored, apart from its use as a tobogganing hill in the winter time. It is galling to compare this obscurity with the resources and attention that are lavished upon a cheesy replica of a so-called Pioneer Village on the other side of the city.

Though the site is some distance from my home, I have made a point of visiting it frequently. It is a haunting and fascinating place that produces in me a feeling that has taken me months to understand. The hundreds of years since Canada was established on Indigenous land have given rise to a detailed and fascinating history. Immigrant populations (by no means all European) have left their stamp on this society. The history of working class and popular struggles here is rich and deep. Nonetheless, as someone from the United Kingdom, I grew up with the historical imprint of a past that stretched back to ancient times. The burial site in Scarborough brings home to me that, on this stolen land, a similar imprint can be found but it is concealed by a legacy of empire and a colonialism that exists to this day.

Canada shares with other settler colonial societies a deeply rooted desire to deny or minimize the reality of dispossession and to disregard the Indigenous past. Theodore Roosevelt, showing us that Trump is not the first overtly racist American president, declared, “The settler and pioneer have at bottom had justice on their side; this great continent could not have been kept as nothing but a game preserve for squalid savages.” In Australia, the claim of terra nullius (no one’s land) was maintained, as a pretext for genocidal land theft on a vast scale. The more recent Zionist settler colonial project invoked the fiction of “a land without a people for a people without a land” to proceed with the ethnic cleansing of Palestine.

A challenge to the colonial present in Canada will require much more, of course, than adequately marking and honouring ancient Indigenous sites. Indeed, we could imagine Justin Trudeau offering yet another tearful apology at such a location, as he signs off on another pipeline across Indigenous land. However, it is also valid to say that a decolonized society, far from wanting to conceal or disregard the record of earlier Indigenous societies, would display with pride and wonder a history that stretches back over thousands of years.

Solidarity march on the 30th anniversary of the Kahnawà:ke Uprising, Toronto. Photo by Jay Watts/Tumblr.

Decolonizing society

The great problem that exists with the poor excuse for reconciliation that the Liberal Party of Canada peddles is that it puts a dubious offer on the table of repairing the wrongs of the past, even as it reproduces and intensifies them in the present. The hypocrisy and duplicity that Trudeau personifies is only an attempt to deceive and disorient all the more effectively in order to pursue the colonial project. The real hope for a decolonized society is to be found in the unbreakable resistance of Indigenous people themselves. This resistance stretches back into the past and continues to be waged. As I write this, the 1492 Land Back Lane struggle unfolds in Ontario and Mi’kmaw fishers and their allies on the east coast defy racist violence and police collusion as they claim their rights. There is, however, another side to the question that flows from the nature of the settler society built on this land. That society is itself divided along class lines, and both the foundation and imperative exist to develop an anti-capitalism that is also fundamentally anti-colonial.

The Irish revolutionary James Connolly understood that the Protestant population that had been brought over from England and Scotland so as to dispossess the Catholic Irish, especially in Ulster, were not all wealthy oppressors. As he put it:

the Protestant common soldier or settler, now that the need of his sword was passed, found himself upon the lands of the Catholic, it is true, but solely as a tenant and dependant. The ownership of the province was not in his hands, but in the hands of the companies of London merchants who had supplied the sinews of war for the English armies, or, in the hands of the greedy aristocrats and legal cormorants who had schemed and intrigued while he had fought.

With this perspective, Connolly worked as a trade union organizer to unite Catholic and Protestant workers in Belfast in a common struggle against their employers.

All non-Indigenous people who live on this land can be called settlers with perfect accuracy. The society they are part of is exploitative and deeply racist. Those who own the oil and gas companies or the mining operations have an interest in furthering the agenda of resource colonialism. The political establishment wants to perpetuate the system of control and domination that has been imposed on Indigenous people. However, the low wage precarious worker, the woman living on sub-poverty disability benefits, the members of a community that takes to the streets to challenge racist police violence or those who struggle in the face of unfolding climate disaster have a very different set of interests.

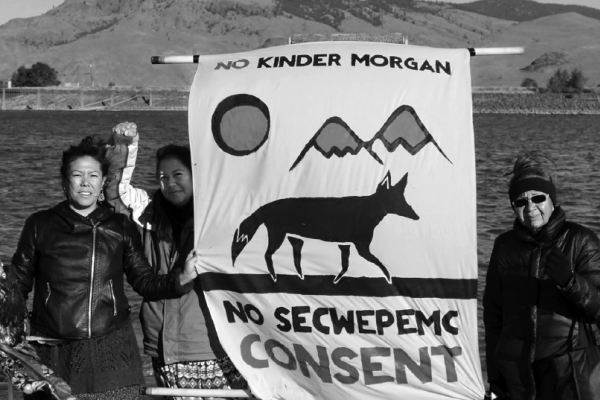

The pandemic has set in motion a deep economic crisis and the period ahead will be marked by a struggle over who pays for that crisis. Last year, Canada was shaken to its core by the struggle that was sparked by the resistance of the We’tsuwet’en. Across the country, Indigenous people and their non-Indigenous allies took action against the colonial brutality and environmental destructiveness that was exposed by the RCMP raids on the encampments of the land defenders. The fight back that was taken up was economically disruptive and enormously inspiring. It pointed to the kind of movements of resistance that are possible in these times.

I began with the Indigenous burial site near my home, surrounded by a suburban sprawl that would have been unimaginable to those who lie at rest there. They never experienced colonial oppression and lived as members of a society that had its roots on that land stretching back into the mists of time. The society that has come into existence since they closed their eyes has brought great injustice and suffering to their descendents. It is a society that denies Indigenous communities clean drinking water but it is also one that allows for-profit care homes to collect government aid, while paying millions to shareholders, even as a pandemic claims the lives of hundreds who live and work in these facilities.

The destructive greed and irrationality of the society that has been built over the bones of those Wendat people condemns it utterly. We need one based on human solidarity that rejects colonialism as an abomination and respects and cherishes Indigenous rights and Indigenous sovereignty.

John Clarke is a writer and retired organizer for the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty (OCAP). Follow his tweets at @JohnOCAP and blog at johnclarkeblog.com.