Rebuilding Canadian post-secondary education

Canada has a chance to lead the world in higher education, if it can fix its own long-neglected system first

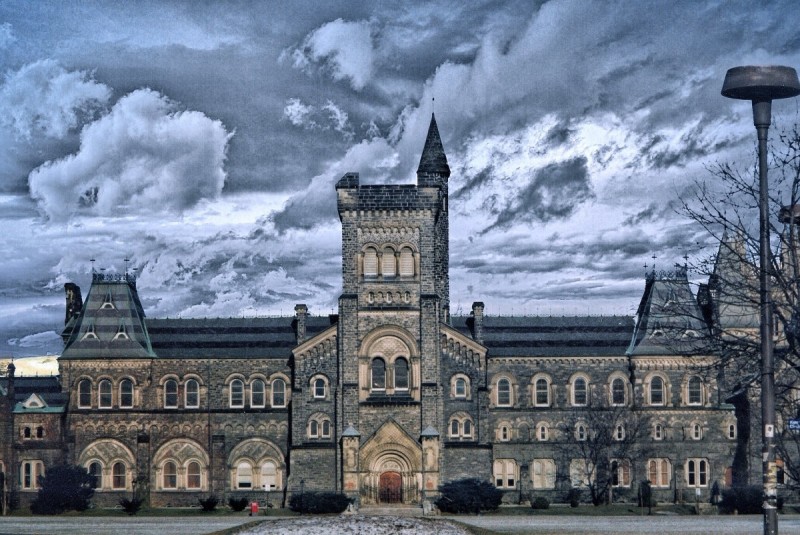

University of Toronto. Photo by Bill Badzo/Flickr.

In the United States, the Trump administration has launched an assault on colleges and universities. In addition to cutting billions in federal research funding, the US government has taken other steps to undermine universities financially, like revoking their tax-exempt status. In its budget proposal for 2026, the government also indicated its plans to reduce the amounts of annual Pell Grants for low-income students, and to cut by over 80 percent federal funding provided for work-study programs. Meanwhile, non-American academics and students who have criticized the Trump administration, or simply expressed opinions that it disagrees with, have been denied entry to the US or deported.

This opposition to higher education is ideological. Speaking in 2021 at the National Conservatism Conference, Vice President J.D. Vance stated plainly that “the professors are the enemy,” and that “we have to honestly and aggressively attack the universities in this country.” Universities are seen by American conservatives as unacceptably secular, progressive, and unreflective of their values. Coming at a time when many colleges and universities were already facing financial pressure from declining enrolment and decreased state support, the recent federal cuts are especially damaging.

This attack on American colleges and universities is a disaster for the advancement of knowledge, but an opportunity for Canada. Canadian institutions have long lived in the shadow of their British and American counterparts. The dismantling of American post-secondary education is leading many academics and students to look for greener pastures elsewhere, and Canada is a good option. American scholars like Jason Stanley have already fled the US—which he described as at risk of becoming a “fascist dictatorship”—and taken up positions in Canada. International applications are also expected to rise at Canadian schools, as applicants seek alternatives to studying stateside. Perhaps now it is time for Canada to step out of America’s shadow and lead the world in research.

There is a wrinkle in this plan though: Canada has been quietly underfunding its own colleges and universities for decades. The most recent expansion of post-secondary education came in the 1960s and involved significant public investments. In the 1980s, the federal government changed the way that the transfer payments to the provinces for post-secondary education were structured. This led to a reduction in federal funding from approximately 0.5 percent of GDP in 1984 to 0.2 percent by 2015. During the same period, provincial funding for post-secondary institutions declined as well. Ontario, in particular, has invested the least per student in its universities despite being home to 40 percent of Canada’s universities.

A dearth of public funding has caused many post-secondary institutions to go searching for funding in ways that have been detrimental to them. For instance, the University of Toronto pursued a risky investment strategy that caused it to lose $1.3 billion during the 2008 financial crisis, including 30 percent of its pension and endowment funds. Another approach to making up for funding shortfalls has been to increase international student enrollment and tuition. As a percentage of enrollment at Canadian schools, international enrolments increased from 7.2 percent in 2010-2011 to 18 percent in 2021-2022. Meanwhile, international tuition is generally five times higher than domestic tuition, and rose by 34 percent between 2018 and 2024. Since tuition rates for domestic students are capped by the provinces, but international student fees are unregulated, the latter are used to raise money.

This approach has created a number of problems. In the first place, international students are taken advantage of, and bilked for as much money as possible. The classist and meritocratic implications should also be clear. For international students, admission is less a question of academic potential or achievement than it is a question of who has the money. A smart student from a poor or working class family in another country has no realistic chance of studying in Canada, unless they obtain a rare scholarship. When those with fewer means do attend Canadian institutions, often their family has pinned all their hopes and savings on that one child, creating an immense amount of pressure. International students experience higher levels of stress and burnout than domestic students, often have to work longer hours to support themselves, and will leave school with a higher level of debt.

Since international students are recruited primarily for their money, some are admitted regardless of whether they possess the basic skills necessary to succeed. This creates a situation that is unfair both to those students and the instructors tasked with teaching them. If an instructor wants to help their students succeed, they will often end up performing extra, unremunerated work to assist them. The situation also places pressure on instructors to lower academic standards, since the university wishes to retain these students for financial reasons, and it is emotionally difficult to fail a student who must either pass their courses or eventually be made to leave Canada. Compare this to public universities in a country like Germany, where tuition is free for domestic and international students. There, academic institutions recruit students based on achievement, and avoid most of these issues.

In 2024, the federal government introduced a new cap on study permits for international students. The 2025 limit is 437,000 permits, which is a reduction of 10 percent from the previous year. This shift towards limiting international student enrollment means that colleges and universities can no longer rely on it to make up for a lack of public funding. The consequence will be layoffs of staff, hiring freezes for faculty, and the closure of programs. In Canada, instead of electing a government eager to go to war with our schools, we have simply neglected them as they slowly starve to death.

Canada could be an educational superpower. Taking advantage of the brain-drain from the US, we could recruit the best and brightest to fill our labs, faculty lounges, and classrooms. By leading the world in research, we could build back up some credibility and soft power on the world stage that we have lost in recent decades. However, this would require new public investments in education.

While Ottawa considers spending five percent of GDP on defence, it should ask itself why we spend only 0.2 percent of GDP on our universities. If they can solve that riddle, maybe someday instead of McGill being called the “Harvard of Canada,” we’ll be calling Harvard the McGill of America.

Eric Wilkinson is a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Philosophy at the University of British Columbia.

_600_400_90_s_c1.jpg)