Why Concordia got it so wrong with eviction of student residents during COVID-19

In the late morning of Wednesday, March 18, many of the approximately 800 students living in residence at Concordia University in Montréal received an email from Lauren Farley, Director of Residences, informing them that they would be evicted in four days, on Sunday, March 22.

The email did not even reach the entire residence body, leaving some students to hear about their eviction through word-of-mouth in the lunch halls that day. For the residents who did not receive the initial email, they would get written notices a few hours later, when the entire student body received an email stating:

In light of the current [COVID-19] health emergency, and in particular, for the safety of those students living in residence for whom social distancing measures are difficult to maintain, all students are required to move out of residence by the end of the day Sunday, March 22, 2020.

The residents were told that the remainder of their rent and meal plans would be reimbursed (though no timeline was provided), and that “exceptional circumstances” would be reviewed for permission to stay beyond the March 22 move-out date. But that was it. The brutal and opaque eviction notice sent students reeling to find new housing in the opening weeks of a global pandemic. While world leaders and social networks pleaded with the public to stay home in order to slow the spread of COVID-19 outbreaks, over 800 students were given four days notice to find a new place to stay.

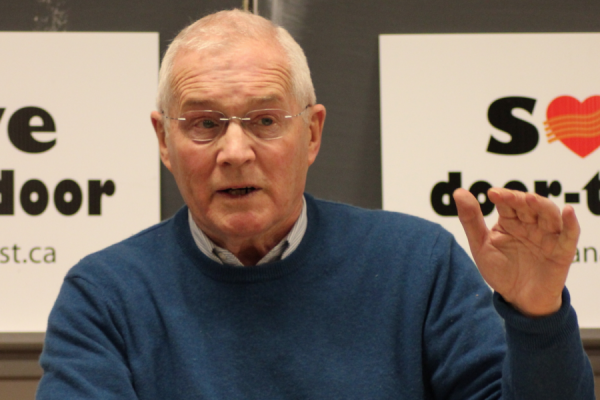

As criticism and concern emerged across the student body, faculty, and the broader Montréal public, Concordia circulated a statement written by university president Graham Carr, reiterating that the decision was made “in consideration of the welfare of our students, our residence staff and our community” and out of concern for the “health and safety of our community and [Concordia’s] civic responsibility to Quebec society.”

So often, universities are heralded as paragons of expertise, logic and altruism. How Concordia interpreted the mass eviction of hundreds of its students in the midst of a global pandemic to be a measure of health and safety is unfathomable.

Eviction

Evictions are traumatic events, even without the added context of a global pandemic. Before I moved to Montréal to pursue a master’s degree, I worked as a Housing Coordinator in an eviction prevention program in Winnipeg’s West Broadway neighbourhood. Eviction prevention is widely understood to be a best practice for tackling housing insecurity, because tenants and housing workers around the country know that relocation is an incredibly resource-intensive process.

Moving is expensive and arduous. But moving with little notice causes people to move into less-than-ideal conditions. This means taking on rent one cannot typically afford, moving into a unit with pests, entering a lease on predatory terms, or moving into harmful domestic relationships.

Studying eviction in Milwaukee, Matthew Desmond writes that eviction almost always results in at least two moves: “a forced move into degrading and sometimes dangerous housing and an intentional move out of it.”

Over the last year or more, students made a home in Concordia’s residences. In November, a classmate who was living in residence told me that it was difficult to establish a sense of belonging in Concordia’s pre-furnished rooms. Yet, as she explained, there was already a sense of solidarity building among the residents; they held conversation over shared meals and met in common spaces. I was pleasantly surprised to hear that my friend had already formed so many social ties. For the rest of us who had only recently moved into apartments throughout the city, we had rarely even met our neighbours.

The eviction fractured this sense of home, scattering social ties across what many students would still find to be an unfamiliar city. Many would leave Montréal or Canada entirely, seeing their degree slip away only weeks before the end of term. It is not hyperbolic to say that Concordia abandoned these students.

What happened to the students?

By Thursday evening, March 19, one resident informed me that most of the others had already left or were packing their belongings and preparing to depart. President Carr’s statement offered that students who had nowhere to go would be supported “to the best of [the university’s] abilities.” Immediately after the statement was released, however, residents received another notice doubling down on the March 22 move-out date.

As the university doubtless expected, many students aimed to return home. For international students, this meant purchasing uncertain flights at exorbitant costs while a travel ban was about to be rolled out. Even if they were able to return home, these students would be required (at various intensities according to their home countrys’ policies) to self-quarantine, and would have to negotiate putting family members at risk. For domestic students, many would struggle with the same decisions.

Indeed, most students would be thrown to the wolves, forced to search for new housing in a city facing a vacancy crisis. While Montréal’s vacancy rate sits at 1.5 percent, several neighbourhoods within walking distance of Concordia’s campus have vacancy rates well below one percent. In the extraordinary situations where students could find apartments, they would have no choice but to take what was made available to them.

Last summer, as I and other students moved to the city, we were often faced with the choice of accepting an illegitimate rent increase or continuing our search in a tight and fast market. Faced with four days to find housing in the middle of the month, there would be no such luxury to pass on predatory leases.

The Montréal community responded by opening its doors, a tremendous display of mutual aid in a time when we will all be confined to our homes for the foreseeable future. In social media threads, people offered couches and spare bedrooms to accommodate the displaced. While this generosity is worthy of celebration, we cannot forget that these living situations are not secure in the long-term and will result in overcrowded apartments. These students are without a home, and Concordia still has a role to play in ensuring they don’t fall into absolute homelessness.

How did this happen?

We should ask ourselves the same questions that residents were asking on March 18—how could this happen? Concordia can’t evict everyone, can they? Do students in residence have tenancy protections?

In the end, Concordia was able to evict over 600 students in two days through mixed messaging, harsh paternalism, and a general lack of transparency.

To the general public, Concordia insisted that the decision was made out of care for the health and safety of students. Exceptions would be made for those who could not leave. But immediately after these statements, residents received memos reminding them of their eviction. The confusion caused students to panic. Unwilling to risk their housing on unreliable information from the institution, they looked elsewhere.

Carr’s statement claimed that the layout and shared spaces of the dorms made it difficult for students to properly self-isolate. Several other Canadian universities have begun to scale down their dorms out of similar concerns. However, while other institutions have asked those who are able to leave to do so, Concordia resorted to mass eviction. Only hours before receiving their first eviction notice, students were asked to complete an online survey identifying whether they were able to leave, or were planning to vacate their dorms. For a moment, it seemed as though the administration was trusting residents to make the decision for themselves, but soon enough this agency was pulled out from under them.

Pushing students out was a form of paternalistic tough love, but the iron fist of mass eviction came with a proviso: Concordia had a contingency plan.

President Carr’s statement offered that “Concordia will support any student currently in residence who has nowhere to go to the best of our abilities by providing them with accommodation, meals and other services until conditions improve.”

Similarly, in an email thread with Andrew Woodall, Dean of Students, I was told that no one would be kicked out, and that if anyone was worried, they should contact the Director of Residences for assistance. However, when asked if Concordia would therefore publicly retract the March 22 move-out date, Woodall insisted “no, that [is still] the date.”

To their credit, the history department demanded from the administration a public statement on how Concordia would accommodate students who could not leave, and insisted that new accommodations should be demonstrably more secure against the spread of COVID-19 than the student residences. At the time of writing, however, after more than 600 students have been forced to leave their residences, a statement has yet to be made.

When pressed for information about the relocation plan, Woodall shut down any opportunity for transparency, stating “the staff are in close contact with the students in their residences. We will know where people are going and no one will be forced out if they don’t have somewhere to go.”

In truth, there was a never a contingency plan for the 800 students. Concordia’s residences are staffed by eight employees, and these roles are primarily administrative. The university manages on-site support by selecting senior student residents to act as ‘Residence Assistants’. While students were scrambling to find new housing this weekend, the only resources immediately available to them were Residence Assistants and security guards.

Even if the university sought to find secure housing for a fraction of the students, this would have required a small army of housing workers. Keep in mind that most of these students have never searched for an apartment before last weekend, never mind one in a new city under specific provincial tenancy legislation.

This brings us to our last question: what sort of protections did these students actually have?

Student residences often exist in a grey area as far as tenancy rights are concerned. This makes it confusing for students, who may not know if their housing falls under the protection of the Régis de Logement. However, the students living in residence at Concordia are under regular lease agreements with the university, which means that they do in fact have the same rights as a normal tenant. The four-day eviction notice was therefore unlawful.

The eviction notice came only two days after the Québec government suspended all eviction hearings related to an inability to pay rent. While evictions for health and safety reasons are still being heard, Concordia would have needed to defend this decision before a tribunal. The university’s snap judgement will be blamed on a state of exception, acting out in an unprecedented moment of crisis, but the fact remains that the mass eviction was unnecessary, unethical, and very likely illegal.

What can Concordia do?

Concordia still has a responsibility to its residents, and it still has the infrastructure to follow-up with the evictees. The following is a plan of action that the University should take immediately:

- Publicly and openly apologize to students who were evicted.

- Publicly and openly invite any student to return to their unit for the remainder of their lease.

- Evicted students who drop classes should be reimbursed in full.

- Pay three months’ rent plus moving costs to any student who was forced to move (as is consistent with other unit repossessions in Quebec).

- Reimburse students for their outstanding rent and meal plans, as well as the tuition, three months’ rent and moving costs listed above, and make public the timeframe for repayment.

This is truly a difficult time for all. The university has shuttered its doors, offering only essential services for the remainder of the term. Housing and food, however, are undeniably essential services. We have not seen other housing providers take such drastic measures, and we cannot normalize mass evictions during a pandemic. Concordia University has a debt to pay.

Stefan Hodges is a geography graduate student based in Montréal. He research interests include housing in crises, and he is inspired by radical softness and the antagonistic force of humour. Stefan occassionally plays in rock bands. Follow him on Twitter.