Decriminalization is only half the story

Drug liberalization reduced overdose rates in Europe. Why isn’t it working here?

Rally to end the war on drugs, Los Angeles. Photo courtesy Drug Policy Alliance/Flickr.

British Columbia began a three-year experiment with drug decriminalization at the beginning of 2023. After some adjustments to the law earlier this year (the use of drugs in public has been recriminalized, in alignment with legislation around public alcohol consumption) adults can now legally possess up to 2.5 grams of heroin, fentanyl, cocaine or methamphetamine in their homes without being arrested, charged, or having their drugs seized.

Decriminalization challenges the ethically dubious proposal of imprisoning people for the things they choose to put in their bodies. As a policy, it acknowledges that confining people in traumatizing carceral institutions has no impact on broader social patterns of substance use and that decades-long drug wars are, therefore, a suboptimal use of state resources.

Loosening law enforcement’s grip on drug users is a controversial idea. It is often claimed that more permissive drug laws will result in more people using—and dying from—substances. In its most histrionic form, this argument asserts that relaxed drug laws turn urban centres into “scenes from zombie films.”

After almost two years of decriminalization, we can put these claims under the miscroscope.

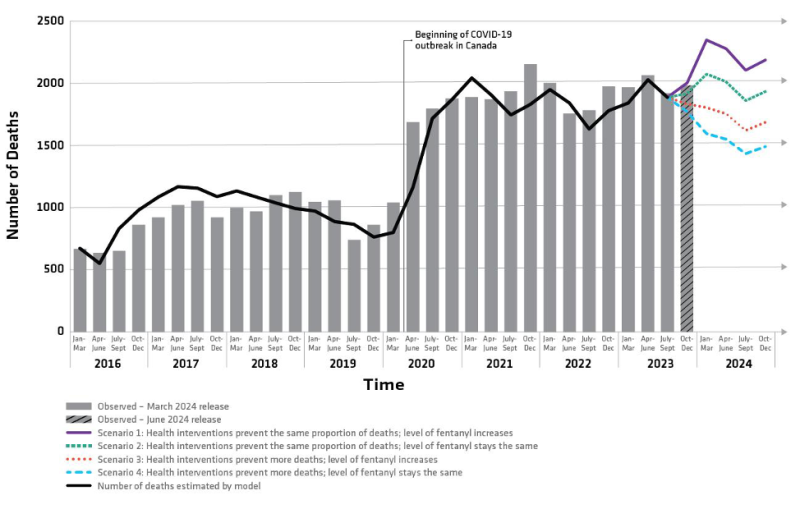

The data out of BC shows no evidence of increased use post-decriminalization. In fact, in alignment with global trends, drug poisoning fatalities are actually falling.

Despite these unambiguous results, the chattering classes have decided to cast decriminalization as an unmitigated failure. Pearl-clutching editorials that appear in the mainstream press suggest that the opioid epidemic has gotten worse. Highly visible public disorder, a perceived lack of public safety, and the death of almost 200 people every month in BC alone all contribute to the impression that decriminalization just isn’t working.

This perspective is perhaps best represented by prime ministerial hopeful Pierre Poilievre, whose proposed response to the crisis consists of recriminalization, shuttering safe supply programs, and introducing forced treatment.

Poilievre believes permissive drug policy has created this crisis and only a “tough,” “commonsense” approach will end it.

While it is true that there was an intensification of the drug crisis at the beginning of the decade, it does not coincide with the passing of decriminalization in BC in 2023. Larger forces are at play here. Two globally significant events prompted the sudden intensification of the opioid crisis: first, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, which disrupted black market supply chains, and second, the recapture of Afghanistan by the Taliban in August 2021, which decimated global heroin production.

With poppy fields burning and traditional smuggling routes closed down, drug traffickers had to get creative to meet the rising demand for substances prompted by the sudden isolation and uncertainty of the pandemic. They began selling whatever they could get their hands on. Drug testing indicates that since 2020 the drug supply has become an unpredictable blend of benzodiazepine, xylazine, and fentanyl. At the start of the 2020s the nation’s black market drug supply became a witch’s brew.

Opioid-related deaths during the overdose crisis. Graph courtesy Health Canada.

The spike in overdose rates across the country—indeed globally—preceded BC’s decriminalization experiment by years. Blaming nationwide increases in opioid deaths on one province’s experiments with decriminalization is both historically and medically inaccurate.

Decriminalization represents a détente in the drug war which has so far had no observable negative effects, but it is indisputable that decriminalization alone has not and will not reverse the opioid epidemic. After all, legal tinkering is no replacement for effective addiction services. Nowhere is this illustrated more clearly than in Portugal where the government’s 2001 decriminalization of drugs was accompanied by complementary investments in health and human services. These twin policies saw overdose deaths and have kept them below EU averages ever since.

The Portugal model has also seen the number of people entering voluntary treatment programs increase while HIV infections, problematic drug use, and incarceration for drug-related offences have declined. This success is due to massive investments in harm reduction and health infrastructure which allow care providers to attend to the wellbeing of each individual.

In Portugal, people who use drugs are referred to a Dissuasion Commission comprised of care providers who makes decisions on a case-by-case basis. If the person’s drug use is not a problem, the commission can simply dismiss the case. However, if the person is using in a way that poses a risk to themselves or others, the commission can order sanctions that range from fines to social work or group therapy. The majority of people who appear before the commission receive no sanction or intervention and the matter is completely dropped. For people who appear to use drugs frequently and problematically, the commission will make referrals to treatment, which is always voluntary and never mandated.

Unfortunately, over the last decade progress has stalled. Austerity politics has led to significant cuts to the social infrastructure essential to the success of the Portugal model. As a result, people who use drugs are once again finding themselves entangled in the court system.

Portugal’s experience teaches us that decriminalization is a half measure. While taking addiction out of the hands of criminal justice is a sensible decision, it is clearly not enough. Decriminalization does not address toxic supply, criminal control of the drug trade, or the inadequacy of existing health and treatment resources. What is needed is legalization coupled with a public monopoly on a well-regulated and controlled drug supply. This must be done in conjunction with massive investments in a full spectrum of health services capable of addressing the diverse needs of people who use drugs.

But even this evidence-based, humane, and effective approach only addresses the symptom. Addiction as a social crisis is downstream from larger political and economic failures. If we want to end the opioid epidemic, we have to think bigger.

To respond to this crisis we must understand its roots. Societies turn to intoxicants when there is suffering without hope; when living conditions deteriorate and the conviction that things might improve become untenable. Addiction is a symptom. Our economy is the sickness.

The only lasting solution to this crisis is the upending of the economic order and the creation of a just and equitable mode of production—one that is able to rise to the challenge of climate breakdown, one that can claw back the wealth that has been hoarded by a tiny few and use it to build a world of abundance, and one that is able to care for, educate, and give hope to all.

James Hardwick is a writer and community advocate. He has over ten years experience serving adults experiencing poverty and houselessness with various NGOs across the country.