Waiting for Hollywood: Canada’s Maquila Film Industry

Hollywood’s Canada, often referred to dreamily as “Hollywood North,” where money grows on palm trees that sprout out of snow banks, is a confused, unstable and increasingly contentious place, as seen in news from Canada’s film and television industry this past summer.

The production in Winnipeg of 3D computer graphics for the Hollywood film Journey to the Center of the Earth, starring expatriate Canadian actor Brendan Fraser, made headlines. The CBC proudly announced that the popular, long-running U.S. gameshows Wheel of Fortune and Jeopardy would be airing on CBC, starting in the fall. The mediocre Canadian feature film with the stunt title Young People Fucking grabbed headlines and provoked Christian fundamentalists, inside and outside the Harper government, to launch new censorship laws to prohibit state support for what they deem to be immoral or pornographic Canadian films. The Harper government continued its assault on state funding of Canadian culture in general and film production in particular, cutting millions from the Canadian Independent Film and Video Fund and from the National Training Program for Film and Video, followed by the largest single cut yet of $14.5 million to kill Telefilm Canada’s New Media Fund. Meanwhile, Ken Ferguson, president of Filmport, a shiny, new, 49-acre complex of state-of-the-art film studios on Toronto’s waterfront, developed at a cost of $275 million, announced with great fanfare on national television, “We are open and we’re waiting for Hollywood.” Tucked away inside this morass of paradoxical and desperate grabs for money, power and headlines, one remarkable Canadian film – Guy Maddin’s My Winnipeg – actually opened in Canadian cinemas. For months, now, Maddin’s film has offered lonely but crucial visible evidence of a vital, non-industrial Canadian film culture that percolates throughout the country in the face of delusions of film-industry grandeur.

There is no Canadian film industry – just talk of a Canadian film industry. There is clearly a vertically integrated Hollywood film industry (production, distribution and exhibition) operating in Canada, and there is intermittent evidence of an under-funded, self-representational and self-determining film culture in Canada. But there is not now, never has been and likely never will be a functioning Canadian film industry. The determining factor in the failure of the Canadian film industry is the Canadian state, through a complex accumulation of betrayals, sell-outs, misguided policies and half-hearted industrial strategies, all serving to undermine, isolate, constrain and control the Canadian film industry and to promote the growth of what I refer to as Hollywood maquila film production in Canada (referred to officially as “foreign location” production).

The collusion of the Canadian state with expansionist Hollywood film-production interests to develop the maquila industry in Canada has deep historical roots. As early as 1909, the U.S. Consul-General in Winnipeg encouraged U.S. cinematic domination of Canada: “In this new country where all forms of amusement are scarce, moving pictures are welcomed, and there is no reason why the manufacturers of the United States should not control the business.” In 1926, the director of the Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau – the first state film-production unit in the world – supported U.S. multinational expansion into Canada, stating that, “American motion picture producers should be encouraged to establish production branches in Canada…. I believe that really worth-while American producers would be glad to make typically Canadian pictures if they can secure the right co-operation, assistance and technical advice.”

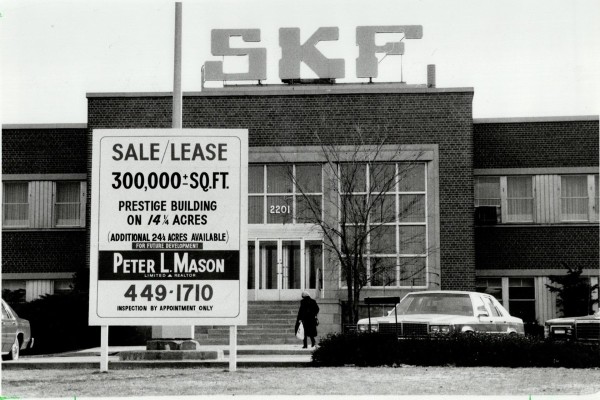

The first example of maquila film production in Canada occurred in 1928, when Hollywood film producers flocked to Canada, particularly Vancouver, to make films that were officially Canadian and could enter the lucrative British market, which maintained a quota on the importation of non-British Empire feature films. Between 1928 and 1938, 22 feature films were produced in Canada specifically for the British market. When the British finally tightened their quota system to exclude these maquila productions disguised as Canadian films, Hollywood producers returned home. As film historian Peter Morris observed in his book, Embattled Shadows: A History of Canadian Cinema, 1895-1939 (McGill-Queen’s, 1978), “Once the reason for the Americans having their branch plant production no longer existed, they removed themselves, their capital and their technical know-how. And Canada was left with nothing.” This period established a pattern of maquila production in Canada that continued intermittently until the early 1990s, when a range of factors made Canada once again the preferred location for Hollywood production.

Hollywood films occupy 98 per cent of screen time in Canadian cinemas and have done so since the birth of the medium. Breaking this number down, locally produced French-language films occupy around seventeen per cent of screen time in Quebec, leaving an average of less than one per cent of screen time for English-Canadian films in the rest of the country. The Canadian state has never, and most likely never will, impose state regulations to establish a quota for Canadian films on Canadian screens. In effect, the exhibition sector in Canada is fully integrated into and dependent on the U.S. production sector. To counter this almost absolute domination, the Canadian state has implemented a range of production-support measures to support the globally integrated film industry – in effect, the Hollywood film industry.

Since the implementation of CUSFTA and NAFTA, in 1990 and 1994 respectively, Canada has complied with the national-treatment requirements of those trade agreements, which require that Canadian state support for a Canadian industry, other than direct grants, must be made equally available to industries operating in other signatory nations. For the film industry, however, Canada reformulated production-subsidy processes to strategically extend Canada’s integration into the global film industry, reinforce the domination of Canadian screens and further undermine the development of a viable Canadian film industry. In 1997, the federal government launched the Film or Video Production Services Tax Credit (PSTC) which offered Canadian and foreign-owned companies a tax credit of eleven per cent (increased to sixteen per cent in 2003) of salary and wages paid to Canadian employees on productions shot in Canada.

Together with the lowered value of the Canadian dollar and low labour costs, this incentive opened the floodgates to maquila film production in Canada. In 1996, the year preceding the introduction of the PSTC, maquila production exceeded Canadian production, with $320 million in production expenditures of the total combined Canadian and maquila expenditures of $542 million. In 1998, the year following the PSTC’s introduction, maquila production almost tripled to $834 million in production expenditures, or seventy per cent of the total combined Canadian and maquila expenditures of $1.1 billion. Both the volume and percentage of maquila film production increased as a result of the PSTC, which is a NAFTA- and WTO-compliant, non-discriminatory direct subsidy of Canadian wages and indirect subsidy of Hollywood production.

This indirect subsidy to maquila production by the Canadian federal government was matched by an increasing number of similar tax-credit programs at the provincial level. In fact, provincial competition within Canada to attract maquila production was and remains fierce. Almost all of Canada’s ten provinces and three territories now maintain labour- or production-cost tax credits for maquila production that match or exceed the federal program. Manitoba established the most aggressive tax-credit rates, with 35 per cent of salaries paid to Manitobans and a total of ten per cent of production costs eligible for credit. As a result, between 1997 and 2002, Manitoba’s foreign location film production grew by 177 per cent and even attracted Canadian productions from other provinces where tax credits were lower. In dollar terms, with 51 per cent of foreign location production occurring in B.C., that province garners the greatest portion of foreign location production, followed by Ontario with 33 per cent.

Hollywood maquila production throughout Canada continued to grow dramatically between 1999 and 2004, while Canadian film production stagnated or declined. In 2002, a combined Canadian and maquila total of $1.1 billion was spent on film production in Canada. Of that total, $737 million, or 69 per cent, was spent by maquila production. Canadian film production accounted for $325 million, a decrease of ten per cent from the previous year. In 2003, the same combined Canadian and maquila total of $1.1 billion was spent on film production in Canada. However, of that total $842 million, or 76 per cent, was spent by Hollywood maquila film production, an increase of nine per cent over the previous year. Canadian film production accounted for $260 million, or only 24 per cent, of the total expenditures. Over the five-year period from 1998 to 2003, Hollywood maquila film production grew by 23 per cent while Canadian film production decreased by three per cent.

Combining all levels of tax credits and the indirect subsidy of the lower Canadian dollar, a typical maquila production budgeted at U.S. $43 million could reduce costs by at least 57 per cent, or U.S. $24.5 million, by shooting in Canada. Extrapolating this savings rate to the total maquila production expenditures of just over Cdn. $1 billion in Canada in 2006, various Canadian governments provided indirect subsidies of $570 million to Hollywood production.

This is over ten times as much as the $48-million amount allocated by the federal government that same year to Canadian feature-film production through its film-subsidy agency, Telefilm Canada. Even factoring in federal tax credits for Canadian productions, along with provincial production subsidies and tax credits for Canadian productions, the total amount of state monies available to Canadian film production cannot come even close to matching the total state indirect subsidy to maquila production in Canada.

To add insult to injury, completed maquila productions return to Canada through the Hollywood monopoly on exhibition in Canada to sustain the exclusion of Canadian films from Canadian screens. This overall strategy to support the short-term growth of employment for Canadian technical crews through the long-term growth of Hollywood maquila production, while simultaneously provoking the decline of Canadian production, constitutes state-supported foreign dumping in its own market, or “self-dumping.”

In 2004, the fickle, nomadic nature of maquila industries re-appeared in Canada, as Hollywood production began to decrease for the first time in almost a decade. The 2003 SARS crisis in Toronto and the increase in the value of the Canadian dollar to U.S. $0.84 in 2004 prompted many Hollywood productions to return to Hollywood or to relocate to more favourable countries, like Hungary, Czechoslovakia and New Zealand. As well, unemployed technical workers in Hollywood (grips, set decorators, electricians, drivers, etc.), who were most directly affected by the employment of Canadian technical crews in the maquila industry here, began to organize opposition to maquila productions in Canada and to Canadian state subsidization of Hollywood productions as an unfair competitive advantage.

In October, 2004, the U.S. Senate passed tax-credit legislation similar to Canada’s in order to attract maquila productions back to the U.S. Maquila production in the province of Ontario alone dropped by 36 per cent in 2003, prompting Canadian film-industry associations to lobby all Canadian governments to take action to save maquila production. In December, 2004, the Ontario government increased the tax credit for maquila film production from eleven to seventeen per cent, launching another round of increases in tax credits for maquila film production in all other provinces. Quebec raised its production-services tax credit to twenty per cent in December, 2004; B.C. raised its credit from eleven to eighteen per cent in February, 2005; and Manitoba raised its own to a maximum of fifty per cent. At the same time, the federal government shifted monetary policy, lowering the value of the Canadian dollar from U.S. $0.84 in 2004 to U.S. $0.80 in 2005.

As a result of these measures, maquila film production began to return to Canada. In 2006, maquila production in Canada returned to pre-SARS levels, almost all of the increase occurring in B.C. But with maquila industries, nothing is certain. Waiting for Hollywood is a very perilous, high-stakes game.

Given the ongoing collusion between the Canadian state and the Hollywood maquila film industry, it is clear that the state cannot be counted on to enact policies that address the century-old failure of the Canadian film industry. As Andre Lamy, the former director of Telefilm Canada, explains: “The problem with the film industry in Canada is that it is precisely not an industry…. Any policy solution based on the belief that such an industry exists will only lead to catastrophic results.”

Clearly, a radical re-theorization and reorganization of policy processes outside of the state and outside of the global maquila film industry are required to develop approaches that support and extend the non-industrial, self-determining, self-representational film culture we already have in Canada. Established Canadian film-culture directors like Guy Maddin, Deepa Mehta, Peter Mettler and Robert Morin consistently make feature films that are adamantly non-industrial and that continuously challenge our perceptions of ourselves with piercing portraits of how we really live. Younger filmmakers like Noam Gonick and Kent Monkman challenge both industrial conventions and received notions of self in their films, while spilling over into art practice with their cinematic/architectural installations in galleries.

Everyone with a computer and Internet connection now has access to the means of self-representational image production and distribution, demonstrating that the principles of direct democracy are increasingly the concepts that guide emerging digital representational processes. It is this broad-based distribution of non-industrial creative practices in our distributed network of bottom-up film, art and digital-media cultures that merits support by the state – not through stale and failed free-market industrial policies, but through full subsidy for cultural experimentation granted on direct-democracy principles of self-determination and self-representation.

Further Reading

- Peter Grant and Chris Wood, Blockbusters and Trade Wars: Popular Culture in a Globalized World (Douglas and McIntyre, 2004)

- Dreamland: A History of Early Canadian Movies, 1895-1939, dir. Donald Brittain. NFB, 1974

- Michael Dorland, So Close to the State/s (University of Toronto, 1998)

- Peter Morris, Embattled Shadows: A History of Canadian Cinema, 1895-1939 (McGill-Queen’s, 1978)

- Kirwan Cox, “Hollywood’s Empire in Canada,” in Self Portrait, ed. Pierre Veronneau (Canadian Film Institute, 1980)

- Profile 2007 (Canadian Film and Television Producers Association (CFTPA/APFTQ), 2007)

This article appeared in the November/December 2008 issue of Canadian Dimension .