Training for movements

In these challenging times, we have to generate new and relevant mechanisms for spreading the skills that activists need

Many activist spaces these days spend time developing critical analysis through events, writing, and discussion. But as much as we might wish otherwise, sharp analysis doesn’t automatically translate into the skills required for working in groups, making collaborative plans, and taking effective action. Successful movements create intentional mechanisms for helping people to learn such organizing skills.

There are lots of examples in recent history. The US civil rights movement set up intensive civil disobedience training as well as African American freedom schools. The women’s liberation movement generated consciousness raising groups, peer-topeer education practices, and touring workshops. The labour movement created summer schools, labour colleges, and worker education programs; although much less widespread today, some of these spaces continue to exist.

During the 1970s and the 1980s, the direct action anti-nuclear movement developed a culture of training inspired by the civil rights and feminist movements. In preparation for large-scale civil disobedience actions involving hundreds of people, organizers regularly held workshops on decision making, direct action, and campaign building, among other topics. These trainings, some of which were daylong, combined presentations, facilitated discussions, and participatory activities, often with role-playing.

As historian and activist Andrew Cornell points out, this culture of training carried on into many subsequent movements. It was definitely influential as I came into radical politics in the 1990s. This was a period when activist skill-building workshops and open, training-oriented movement gatherings were much more common than they are today.

During this time, a network of experienced Earth First! organizers offered frequent workshops and touring “road shows” focused on popular education around specific campaigns. Copwatch groups trained interested people in other cities about how to monitor and record local police activity. Similarly, antiracist action groups trained people across the continent in methods for countering white supremacist organizing. Many activists also routinely travelled to multi-day conferences and other gatherings offering workshops on everything from blockades to banner making, meeting facilitation to media outreach.

Arguably, this culture of training peaked with the so-called antiglobalization movement in the late 1990s and early 2000s. What we called “convergences”—gatherings for training and planning—preceded most of the large summit protests of that era. And during those years, it was common for groups involved in the movement to hold periodic workshops on topics such as anti-oppression, consensus decision making, and direct action, as well as more specialized trainings for legal observers, street medics, and others.

Since then, there has been a noticeable downturn in training. Although many experienced activists have mentioned this to me, anarchist sociologist Lesley Wood is the only activist I know who has looked carefully at the trend. Focusing on North American anarchist gatherings, Wood has recently documented a marked decline in skill-building workshops since the 1980s. This is consistent with my experiences over the last two decades.

As with most everything, I’m sure there are many contributing factors. But I suspect that it has a lot to do with prevailing life circumstances amidst 21stcentury neoliberalism. The material realities of most people’s lives right now involve a great deal of precarious low-paid work, much harm and trauma, tremendous debt, and pressing responsibilities to care for children and older family members. So many of us feel exhausted, scattered, anxious, and sped-up. In these circumstances, creating space for training is understandably challenging but all the more crucial.

I find hope in training initiatives that are persevering—and growing—in these difficult circumstances. This is particularly the case in the United States, where there are both long-standing organizations, such as Project South and Training for Change, and newer efforts, such as the Institute for Advanced Troublemaking and The Wildfire Project. In the Canadian context, most university-based public interest research groups (PIRGs) host workshops and, more ambitiously, Tools for Change organizes an annual series of training sessions in Toronto. As well, some labour unions continue to hold training and experiment with online educational spaces for rank-andfile members. I’m also excited about the February 2019 PowerShift: Young and Rising conference in Ottawa, which promises a weekend full of workshops for climate justice activists and organizers.

What can we learn about current movements based on how they are training people? Not only are activists struggling mightily, but our collective capacity is lower than in some previous periods. To build the large-scale, sustained, combative movements we need, we will have to generate new and relevant mechanisms for spreading the skills that activists need.

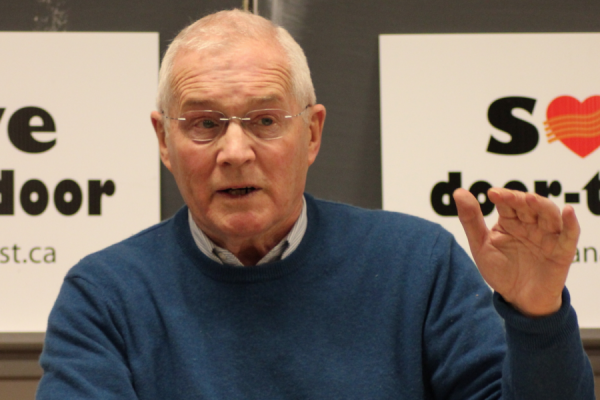

Chris Dixon is a long-time activist, writer, and educator. Originally from Alaska, he lives in Ottawa on unceded Algonquin territory, where he is a member of the Punch Up Collective. Find him online at writingwithmovements. com.

This article appeared in the Winter 2019 issue of Canadian Dimension (Injustice at Unist’ot’en).