Chronicling the decline of the industrial age in Hamilton

Stephen Dale’s new book examines how capital and gentrification are shaping urban space

How do you write a city?

The lives, the languages, the million tangled paths. The strip malls, the mosques, the tents in parks, the queer bars. Exploitative bosses, helpful strangers, sexual violence, racist police. Tattered posters for old demos on lamp posts, reactionary city councillors in the pocket of developers, stolen land criss-crossed with streets with English names.

How do you write it all?

Well, you choose, of course. You listen, focus your message, whittle down the voices you include, and shape your story accordingly.

Stephen Dale’s Shift Change: Scenes from a Post-Industrial Revolution examines the trajectory of Hamilton, Ontario. This city of more than half a million people on the western shores of Lake Ontario was, for most of the twentieth century, synonymous with heavy industry, especially steel and associated manufacturing.

Along with its reputation for dirt and grit and smoke, it became known—particularly after a pivotal victory in the post-Second World War strike wave that shaped labour relations for a generation—for things like trade unions and building militant working class power. It also built a reputation as a place where at least some sectors of the Canadian working class could be proud and prosperous, and have a strong social and political influence on the place they call home.

While deindustrialization has perhaps not been as absolute in Hamilton as in, for instance, some cities in the US rust belt, today the steel industry and manufacturing are a shadow of what they used to be. Starting in the 1980s, the city saw a growing wave of blue-collar jobs lost, never to return, with consequent poverty and shifts in patterns of city life that might euphemistically be described as “urban decay.” Yet in the last two decades, and most rapidly in the last five years, new money has surged into the city—related, among other things, to a relatively vibrant public sector, closer integration into Toronto’s orbit, and (most ominously) waves of gentrification that are transforming working class neighbourhoods.

Though Shift Change covers the Stelco strike of 1946 and a history of the city’s industrial decline, it is Hamilton’s “urban renaissance” that is Dale’s primary focus. Through detailed interviews with people actively involved in the community, it examines how the city’s post-industrial moment is playing out, and the ongoing struggle to shape it. Dale is committed to the idea that new money flowing in is not always bad, and argues that “a rare alignment of factors and some potential quirks of timing indicate that humble Hamilton might become one of the rare examples of a more equitable form of urban regeneration.”

Shift Change poses a binary of big-dollar developers pushing to re-make urban space for profit versus an anti-gentrification sentiment most closely associated with a small but highly visible subset of anarchists in the city, and then offers a neither-nor resolution, suggesting the deep roots of solidarity in Hamilton and a range of experimental projects and reforms from liberal governments might be a path to a new form of post-industrial prosperity that softens the harsh edges of 21st century capitalism.

Though he no longer lives here, author Stephen Dale grew up in Hamilton, and his love for the city is evident on every page. As someone who myself moved to Hamilton in 1993 as a student and who has lived here for the majority of the years since, I really appreciated that. I also enjoyed seeing my local reality, which is so often ignored in favour of yet more stories about Toronto or the national scene, given centre stage, and hearing in print the voices of people who I know and have worked with (and others I know of).

What’s more, far too often, when the city gets attention in media based elsewhere, the resulting articles capture the basic facts accurately enough but arrange them into narrative in ways that feel like they are reporting on some other city. Shift Change doesn’t do that. It successfully gets inside the city’s stories, and it tells them with passion.

Yet, as much as I enjoyed certain aspects of the book, it has some significant political problems. And I think these problems are at least partially related to the text’s very success in capturing some of the dominant stories told in Hamilton, about Hamilton. As someone whose media work over the last quarter-century has often focused on social movements and on stories emerging from struggles of various kinds, I am acutely aware of how the stories told by those most at home in a place—those relatively able to take up public space even when they are not at the very top of social hierarchies—are often not the most politically important if you want to prioritize justice and liberation. There are at least two ways that this shows up in Shift Change.

One feature of the dominant stories told in Hamilton, about Hamilton, is that they tend to powerfully centre whiteness. The most common stories of city-building, of industrial glory days and their decline, and of post-industrial resurgence sometimes, particularly in their more progressive variants, have room to venerate workers, to speak of class and wealth and poverty. But if they do talk about race at all, it is most often in the superficial gloss of the multicultural mode, rather than any kind of anti-racism that sees race and class (and gender) as essentially bound together in organizing our communities and lives. And this is reflected in how Shift Change has taken up the dominant stories that Hamilton tells about itself.

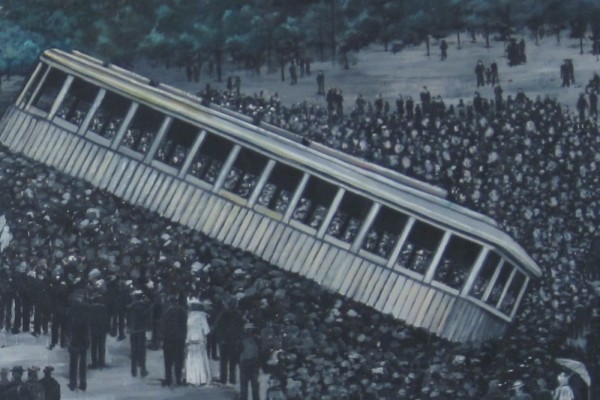

On July 15, 1946, thousands of Stelco steelworkers in Hamilton, Ontario walked off the job, pressing for higher wages, a 40-hour work week and a requirement by the company to regularly deduct dues on behalf of their union. Photo courtesy the Hamilton Spectator.

The voices that it draws in through interviews and then centres in its storytelling are almost all white, while the stories it tells centre whiteness—though silently so—in how they are shaped and how the are told. There are occasional small exceptions on the periphery, but they do not make it to the centre and actually shape the book’s approach.

The relative lack of attention given to Hamilton’s existence on stolen land, to the vibrant Indigenous community in the city itself, and to the city’s close proximity to the Six Nations of the Grand River Territory is particularly troubling. This is, after all, a book that talks a lot about gentrification, and colonization and gentrification as it happens in the context of a settler colonial state are processes that are tightly linked. This absence is doubly mystifying given the two nationally visible land reclamation struggles waged by Six Nations people over the last two decades just outside of what is colonially defined as Hamilton, both of which centrally involved blocking the activities of property developers.

The other big political problem with the book’s uncritical uptake of stories told in Hamilton, about Hamilton, has to do with how it frames gentrification and responses to it.

The original dominant story in the city when money started flowing in and re-making space was unreservedly positive, including on the progressive end of the mainstream political spectrum. There were individual Hamiltonians coming from a range of left perspectives who had grave concerns, but there was very little space to talk about that publicly.

This has changed in recent years. The book suggests this is in part true because of the way in which the aforementioned anarchist tendency forced their unrelenting opposition into mainstream discourse through their rhetorical and tactical exuberance, and certainly the actual harmful impacts as gentrification has ramped up have become impossible to ignore.

The new dominant narrative from which the book takes its framing still sees the in-flow of money into the city as basically positive, but with possible downsides that “innovative thinking and constructive dialogue” might be able to address. Shift Change poses an unpleasant binary—the spectre of rapacious property developers versus irridentist anarchists, looming over the innocent artists and middle-class residents recently moved from Toronto who are caught in the crossfire—and then resolves it by pointing towards pragmatic problem-solving progressives, perhaps aided by higher levels of government with liberal inclinations, that together are the hope for a better future.

While this framing does draw on ways that the issue has developed locally and on how some people here talk about it, it has some serious deficiencies. There really are, for instance, lots of interesting projects happening here, some of which are profiled in the book (many of them will indeed reduce harm, explore alternatives, and create possibilities). For the most part, they are good people doing useful things. But as is so often true of such local projects, their scale is vastly smaller than the scope of the need they are attempting to address.

The book invokes the possibility of action from senior levels of government to compensate for that, asserting that “the magic ingredient is political will.” But in doing so, it exaggerates the impact of the reforms enacted by the previous Liberal government in Ontario (and largely undone by Doug Ford’s Conservatives), and virtually erases the role of social movement organizing in forcing its hand in these areas, thereby also exaggerating the likelihood and scope of potential future reforms. The book then goes on to hypothesize that these two things, in combination with the (very real) legacy of working class solidarity in the city’s culture, might be enough to achieve “an egalitarian form of civic renewal” without significant grassroots organizing and social conflict. While the book’s hope is earnest, I would say, based on observable evidence here in Hamilton and in other cities, it is unfounded.

It is particularly disappointing that the way Shift Change frames the issue leaves no space to recognize, let alone explore, the vast field of possible grassroots collective responses to gentrification that is not captured in either the mix of reforms bestowed from above and local progressive projects the book champions, or the narrow range of militant (but not movement-building oriented) tactics from one quite specific and small group that has at moments seized mainstream attention that it dismisses. It is that field that needs to be at the centre of our discussions if we want to be able to challenge how capital, white supremacy, and settler colonialism are shaping urban space, in Hamilton and elsewhere.

So there is no one way to write a city. You have to get in the middle of it, listen carefully to the voices that you hear, and make choices. And in certain respects, Shift Change succeeds where out-of-town journalists covering Hamilton often fail. But in the process of listening and writing, there is inevitably an element of choice. And I think Hamilton and the impulse to work towards a better post-industrial future would both be better served if that choice had taken steps to decentre the whiteness that so often pervades dominant stories in Hamilton, and if it engaged more critically with stories about gentrification to allow for exploration of the broad possibilities for grassroots movement-building that might actually make it possible to build a more liveable future. And this, in turn, would be a much more interesting and useful example for the many other communities in this country dealing with the loss of manufacturing jobs and the power of capital to re-make space for profit at the expense of people.

Scott Neigh is a writer, media-maker, and activist who lives in Hamilton, Ontario. He is the host and producer of Talking Radical Radio and the author of two books of Canadian history told through the stories of activists, and he has been involved in a range of other grassroots media work since the late 1990s focused on social movements and social issues. Follow him on Twitter @canadianlefty.