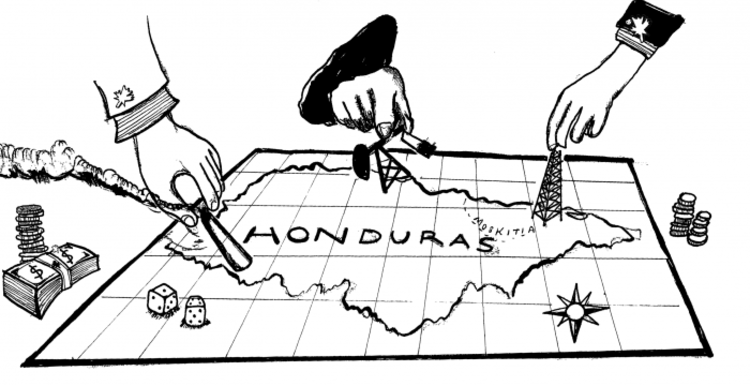

Xiomara Castro’s victory in Honduras is a win over imperialism

Could this open a hopeful chapter in the history of a country marred by interference by the United States and Canada?

Honduran President-elect Xiomara Castro of the left-wing Liberty and Refoundation Party. Photo by El Periódico.

In the November 28 elections in Honduras, voters granted a resounding victory to Xiomara Castro of the left-wing Liberty and Refoundation Party, also known as “Libre.” Castro campaigned on a platform of “democratic socialism” which she asserts will “pull Honduras out of the abyss we have been buried in by neo-liberalism, a narco-dictator and corruption.” Her other proposals include decriminalizing abortion, reducing bank charges for remittances, and tackling poverty and corruption, which she believes to be the “true causes of migration” to the United States. She has also stated that she will seek to rewrite the Honduran constitution, which was written while the country was under a US-backed military dictatorship in the 1980s.

The Libre party was formed in the aftermath of a 2009 military coup that deposed Castro’s husband, Manuel Zelaya (2006-2009). The military repression that followed this deeply unpopular coup plunged Honduras into a period of instability characterized by widespread state and paramilitary violence against journalists, social movements, and the political opposition.

Following the 2009 coup, Honduras had the highest homicide rate in the world and, according to Reporters Without Borders, it became the most dangerous country for journalists in the first quarter of 2010. Scores of activists were murdered in the following years, including Lenca land defender Berta Cáceres, who was one of the most famous activists not only in Honduras, but the entire region. Cáceres was killed in her home after organizing a successful resistance to the Agua Zarca hydroelectric dam project being constructed by Honduran energy company Desarrollos Energéticos, S.A. (DESA) with a Canadian company called Hydrosys. In the following years, it was discovered that former DESA President David Castillo ordered the hit. Three of the eight people arrested for her murder received training at US military institutions, including the infamous “School of the Americas” in Fort Benning.

After 12 years of right-wing rule by the strongly US-backed National Party, which retained power through a series of elections riddled with fraud (even the Washington-based OAS described the 2017 election of Juan Orlando Hernández as “characterized by irregularities and deficiencies, with very low technical quality and lacking integrity”), Castro’s victory represents a new and hopeful chapter in the history of a country marred by imperialistic interference from the United States and its allies – namely Canada.

On December 1st, Canadian Minister of Foreign Affairs Mélanie Joly tweeted “Congratulations @XiomaraCastroZ for making history in #Honduras as the first female President-elect! I look forward to working together on regional priorities: #democracy, inclusive growth, #SRHR and towards fighting corruption.” This statement is interesting for what it omits: Canada’s ardent support for the coup that overthrew Castro’s husband and its silence on the human rights abuses overseen by the National Party from 2009 to 2021.

For the first half of the twentieth century, Honduras was a nation colonized by US capital, its soil stolen in order to grow huge amounts of bananas to profit American companies. During the 1950s and 1960s, domestic capitalist structures grew within this neocolonial framework, resulting in the creation of two bourgeois political parties: the Liberal Party and the National Party. After a period of military rule from 1963 to 1982, the regime oversaw a restrictive transition to a liberal democratic system in which the Liberals and Nationals continued to dominate.

Canadian investment—particularly in the mining sector—began to assume a prominent place in the Honduran economy during the second half of the twentieth century. Canadian mining interests were extremely organized, forming into the Asociacion Nacional de Mineros (ANAMINH), through which they pressured the government to maintain a neoliberal norm in the extractive sector. Historian Tyler Shipley writes: “As early as the 1990s, Canadian mining companies were poisoning Honduran soil and water, killing fish in rivers and toxifying entire communities; one region was described to me as being ‘condemned to death.’” Canada soon became the largest foreign mining investor in Honduras. By 2014, the president of ANAMINH went as far as to assert that “90 percent of foreign mining investments in Honduras are Canadian.”

Meanwhile, Montréal-based Gildan Activewear employed 18,000 workers in sweatshops and industrial parks. It was the largest private employer in Honduras. By 2009, Canada had over $600 million invested in the Honduran economy, making it the second-largest foreign investor in the country. Therefore, when President Zelaya indicated a willingness to transform the economic base of the country in accordance with activist demands, Canada came to regard him with suspicion.

Zelaya, as a businessman and Liberal Party member, was by no means a stranger to the Honduran elite. However, he expressed a willingness to make concessions to the country’s increasingly organized social movements, a fact which alienated him from the entrenched oligarchy. As social movements continued to organize, he made important changes in the form of free school enrolment, stricter environmental protections, and a 60 percent increase to the minimum wage. He also announced plans to convene a constituent assembly to rewrite the dictatorship-era constitution and announced a moratorium on new mining concessions—the latter of which likely perturbed the Canadian government, given that, in the words of one Latin American official, “As far as I can tell, the Canadian ambassador here is a representative for Canadian mining companies.” Indeed, in 2009, a consortium that included Canadian capital offered the Zelaya government $1.75 billion in investment if he lifted the moratorium.

On June 28, 2009, the Honduran military arrested Zelaya, condemning his plans as unconstitutional. He was exiled to Costa Rica while the National Congress read a letter of resignation that Zelaya claimed was forged. President of the National Congress Roberto Micheletti was sworn in an interim president as the coup government planned its next move.

The region swiftly condemned the coup. The governments of Venezuela, Bolivia, Argentina, Ecuador, Brazil, and Paraguay immediately made their disapproval clear in no uncertain terms, and soon every government in the hemisphere had condemned Zelaya’s removal. The Canadian government, meanwhile, waited an entire day before releasing a mealy-mouthed statement in which it called on “all parties to show restraint.” In fact, the only harsh words from Minister of State of Foreign Affairs (Americas) Peter Kent in the coup’s aftermath were in regard to Zelaya’s planned return to Honduras, when he “call[ed] for restraint in the timing of President Zelaya’s return.” For months, Canadian officials also pointedly refused to call the military’s removal of the elected president a coup, referring instead to the “ongoing crisis” within Honduran politics.

Negotiations in Costa Rica between Zelaya and the coup plotters broke down, and the new government hastily organized elections that November. The election occurred in the context of military lockdowns, a massive police presence in the streets, and a muzzled press. This dubious process saw the election of Porfirio Lobo Sosa of the National Party, who was inaugurated on January 27, 2010, while half a million people protested in the streets. Absurdly, Kent congratulated the coup government on “peaceful and orderly” elections run “freely and fairly.”

After his dubious victory, Lobo passed legal immunity for the coup perpetrators and reversed the moratorium on new mining concessions. Canadian companies leapt at the opportunity to expand their holdings even more. From Shipley’s Ottawa and Empire:

There were 154 mining and energy concessions already granted before the moratorium, almost all falling on or around Indigenous territories, of which nearly 100 have been owned by Canadian companies at one time or another during their operation. In 2011, 200 additional concessions were requested; of those, 150 were requested… on behalf of the Canadian company Breakwater Resources Ltd.

A number of other Canadian mining companies that own huge concessions in post-coup Honduras are Maya Gold Company, First Point Minerals, Standard Mining, and Goldcorp.

After Lobo’s inauguration, Kent referred to the arrival of a new government as “the beginning of a process of renewal.” He remained silent on the growing number of assassinations of prominent social activists, including LGBTQ rights activist Walter Trochez, who was kidnapped, beaten, and murdered by men in police uniforms just a few weeks before the inauguration.

February 2010 was a particularly violent month for anti-coup activists. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights reported that:

On February 3, 2010, 29-year-old Vanessa Zepeda Alonzo, who was active in the Resistance Front and was affiliated with the Social Security Employees Union, was found dead in Tegucigalpa. According to eyewitnesses, her body was thrown out of a car. Likewise, on February 15, 2010, Julio Funez Benitez, an active member of the resistance who belonged to the SANAA Workers Union, was holding a conversation on the sidewalk outside his residence in the Colonia Brisas neighbourhood of Olancho when he was killed with two shots fired by unknown gunmen traveling on a motorcycle. Finally, on February 24, 2010, Claudia Maritza Brizuela, 36 years-old, was killed in her home. She was the daughter of union and community leader Pedro Brizuela, who participates actively in the resistance.

Throughout 2010 and 2011, the Harper government was in the process of negotiating a free trade agreement (FTA) with the Honduran coup government. By the end of 2011, 650 human rights workers were facing criminal charges in Honduras and a climate of terror reigned throughout the country, none of which provoked a peep of criticism from Ottawa. Meanwhile, the Harper government assumed a more active role in a supposed “process of renewal” occurring in Honduras by participating in the Honduran Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was convened by the coup government itself. Canada’s representative to the commission, Michael Kergin, later justified the coup against Zelaya by claiming that he was a puppet of Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez. He also excused the bone-chilling levels of murder and repression in the country since 2009 because, in his words, “there is in Honduras a traditional culture of violence.”

In 2013, National Party candidate Juan Orlando Hernández was elected in another deeply compromised election. His campaign was financed with $11 million from Washington and, as it later turned out, money stolen from Honduras’s national pension fund. Protests erupted in the streets at these revelations, but Ottawa showed no concern. In 2014, the Harper government wrapped up successful negotiations on the Canada-Honduras FTA. Minister of International Trade Ed Fast described the FTA as evidence of Canada’s desire to “support positive change” in Honduras. Meanwhile, Harper accused the Venezuelan government of “turn[ing] back the clock on the democratic progress that’s been made in the hemisphere.”

In 2016, the Trudeau government remained totally silent when Berta Cáceres, one of the most renowned and visible human rights activists in the Western Hemisphere, was shot dead in her home in La Esperanza. At the same time, Canadian capital retained a keen interest in Honduras. At the unveiling of a memorial to Cáceres in Fredericton, New Brunswick in August 2021, Tracy Glynn outlined the continued depths of Canadian investment in the country:

After the US, Canada is the largest foreign investor in Honduras. Canadian investments in the country are concentrated in mining, sweatshops and tourism. Meanwhile, hundreds of environmental activists, journalists, lawyers, peasants and LGBTQ activists have been killed by Honduran authorities since the coup. When Cáceres was murdered, a loud message was sent: no activist is safe in Honduras.

Xiomara Castro’s victory last month confirms that, even with the widespread horrors of state repression in post-coup Honduras, the resistance of the Honduran people remains alive and well. While her victory alone will not bring instant change, and while it is doubtless that she will face severe pushback from the domestic oligarchy as well as vested interests in North America, her victory is a clear sign that the people of Honduras remain opposed to the kind of harsh neoliberal governance that Ottawa and its private-sector allies wish to impose upon them.

Owen Schalk is a writer based in Winnipeg. His areas of interest include post-colonialism and the human impact of the global neoliberal economy. Follow him on Twitter @OwenSchalk.