Winnipeg: City of Contradictions

Winnipeg’s history is one of contradictions. On one hand, it was once the “Gateway to the West”–the flourishing outpost on the frontier of Anglo capitalism, where dangers were met and fortunes won. On the other hand, it was the city of labour and struggle–the point of entry for thousands of immigrants who arrived to find a harsh city of destitution and disease. Out of their struggles sprung a wealth of labour and social activism and progressive political thought and organization.

While settlement on the banks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers dates back 6,000 years, Winnipeg emerged as a major city in the 1880s following the establishment of railway access from eastern Canada. This allowed for the movement of capital, goods and the commodities necessary to replace subsistence agriculture with the production of an agricultural surplus for export. Almost overnight, Winnipeg grew from a small community of 8,000 to become the financial, wholesale and retail node of western Canada. By 1913, Winnipeg’s population reached 140,000, making it Canada’s third-largest city.

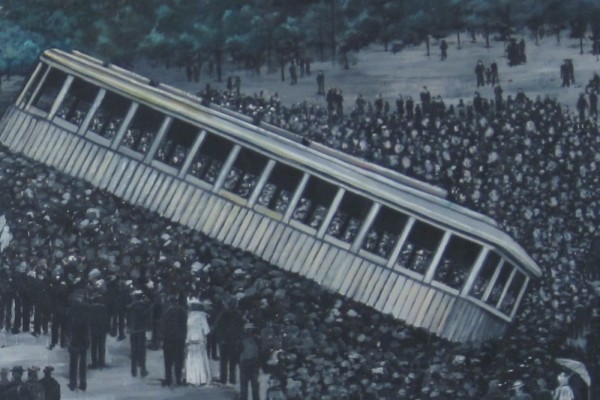

The arrival of labourers at the same time as fortune seekers and business barons set the stage for almost immediate conflict over such things as union recognition, wages, health and safety, the length of the working day, and investment in public works. Despite frequent defeats, important gains were made between 1910 and 1918. Women, who often worked seven days a week for wages far below those of men, played a major role in the labour movement, as well as in the Suffragette movement so that, in 1916, Manitoba became the first province to allow women the vote.

Winnipeg’s business and political elite emerged as migrants from Britain and Ontario arrived to outnumber French and Métis residents and establish an ethnic dimension to the city’s class divide. After 1900, massive numbers of immigrants arrived from Eastern Europe to find a city rife with ethnic hostility. Winnipeg’s ethnic divide persists to this day, with an overlap of British ancestry and higher incomes in the southern and western parts of the city.

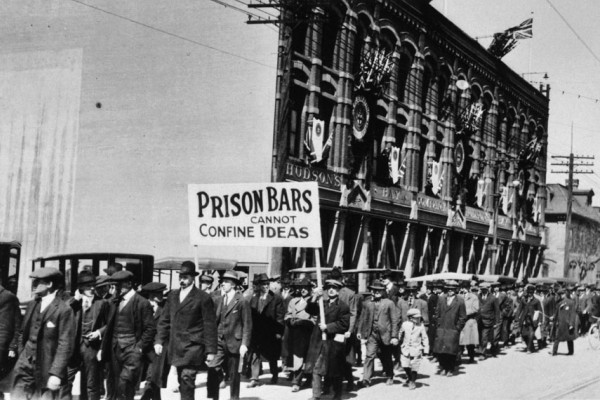

Class conflict culminated in the 1919 General Strike, called to support the metal and building trade unions’ struggles for recognition. The business and political elite of Winnipeg, alarmed at what they saw as Bolshevism, defeated the citywide strike through the arrest of its leaders and a violent attack on its supporters. Despite this, the strike represents a watershed in terms of political consciousness: in the provincial election that followed, 11 labour MLAs were elected, with three of these still in jail at the time. Many, particularly those from the Ukrainian and Finnish communities, gravitated toward the Communist Party, which played a significant role in the labour movement and succeeded in electing candidates, most notably Joe Zuken, who sat on city council from 1934 to 1983. Most workers appeared to prefer a reformist approach, however, like that envisioned by J.S. Woodsworth; he was elected to the House of Commons in 1921 and would go on to help establish and lead the CCF, the forerunner to today’s NDP.

Winnipeg’s dramatic growth began to stall in 1913, with the onset of a recession, the relative saturation of agricultural and investment opportunities and, among other factors, the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914. This latter development allowed goods to be shipped to Vancouver, undercutting Winnipeg’s role as the distribution hub of western Canada; Winnipeg nevertheless soon developed a diversified manufacturing base. The Great Depression and preceding drought, and Alberta’s oil boom, would later confirm Winnipeg’s standing as a slow-growth metropolis–it fell to become Canada’s fourth-largest city in the 1920s, and is eighth-largest today.

In the post-war era, Winnipeg saw expanding public and private service sectors, particularly in the areas of financial and insurance services; a resurgence of immigration from Europe; and, like other Canadian cities, outward expansion in a wave of industrial, commercial and residential suburbanization. Province-wide, the growing urbanization of the rural population and assimilation of immigrant communities traditionally excluded from decision-making processes worked to shift Manitoba’s political geography decisively toward the NDP, making it the second jurisdiction in North America to elect a social-democratic government.

At the local level, a business/development coalition has consistently dominated city hall, and mayors have nearly always been insiders in Winnipeg’s business community, with notable exceptions in Stephen Juba, the city’s flamboyant and first non-Anglo-Saxon mayor from 1957 to 1977, and Glen Murray, the high-profile and first openly gay mayor from 1998 until May of this year. Juba’s tenure lasted through Winnipeg’s “Unicity” amalgamation in 1971, which was a provincially legislated effort to equalize disparities and service burdens, and to reduce competition between the 12 component municipalities.

A number of major government-sponsored projects and development schemes, like the 1981 Core Area Initiative (CAI), have been launched to address the decline of Winnipeg’s core: in a slow-growth context, the flipside of the city’s lowdensity sprawl has become inner-city decline and social polarization. One of Glen Murray’s most notable successes has been to set in motion exciting plans to reverse the serious deterioration of Winnipeg’s downtown, to beautify the city with the help of local artists and to develop Winnipeg’s long-dormant waterfront. With free trade and a low Canadian dollar, Manitoba’s economy shifted through the 1990s to that of an exporter of goods and services to the U.S. Winnipeg, whose mature economy bears little resemblance its early role as an agricultural and transportation hub, has seen considerable growth in its service industries, including call centres, which have brought the city’s old labour struggles into new arenas. And, despite the steady economic growth and low unemployment of the past decade, economic benefits have not been equitably distributed. In particular, the city’s burgeoning Aboriginal population–now eight per cent of the city’s population and the largest urban Aboriginal community in Canada–has been disproportionately left out of the city’s economic opportunities, though this community has begun to see the rise of its own political and professional elite. Months before resigning from office to seek a seat in parliament, Murray launched an urban Aboriginal strategy as part of his New Deal. However, his replacement, business man Sam Katz, Winnipeg’s first Jewish mayor, has shown no interest in advancing this strategy.

Today Winnipeg remains the city of contradictions it always was: it is a city of considerable wealth and energy, and diversified economic growth, but it is also a city of considerable challenge and struggle for those who have found themselves excluded from the benefits of its growth.

Richard Lennon is a researcher and data analyst based in Winnipeg.

This article appeared in the September/October 2004 issue of Canadian Dimension .