Will global inflation subside?

The recovery from the COVID slump of 2020 has petered out, and the world economy is teetering on a significant slump

Photo by Christopher Hollis/Wikimedia Commons

Is the global inflationary spiral peaking? And if it is and inflation is set to fall over the next year, then has the inflation scare been just a momentary blip and now things will start to turn back to the previously low pace of inflation in the prices of goods and services?

That seems to the view of investors in financial assets in the US, where the stock market has rallied by as much as 20 percent from lows in mid-June; and both government and corporate bond yields have steadied. Markets seem to believe in what is called the ‘Fed pivot,’ where the US Federal Reserve, having hiked its policy rate aggressively since April, will now start to end its hikes going into 2023 as inflation subsides.

Certainly, there is some evidence of peaking inflation in the US where the consumer price inflation (CPI) rate slowed more than expected in July to 8.5 percent year over year from a 40-year high of 9.1 percent in June. But looking beneath the headline rate, it is less convincing that US inflation is heading downwards, at least at any significant pace. The slowing in July was mainly due to falling gasoline prices. Food inflation (10.9 percent) and electricity price inflation (15.2 percent) continued to accelerate. And stripping out food and energy, the so-called ‘core’ inflation rate stayed steady at 5.9 percent.

And outside the US, there is still little sign of peaking. The Eurozone inflation rate rose in July to 8.9 percent year-over-year, while the UK rate hit double-digits (10.1 percent), with the Bank of England forecasting a peak of 13 percent-plus by early 2023, and other forecasters calling a 15 percent rate. Even Japan, the economy of stagnation and deflation for decades, achieved a 2.6 percent year-over-year rate in July. This was the 11th straight month of increase in consumer prices and the fastest pace since April 2014.

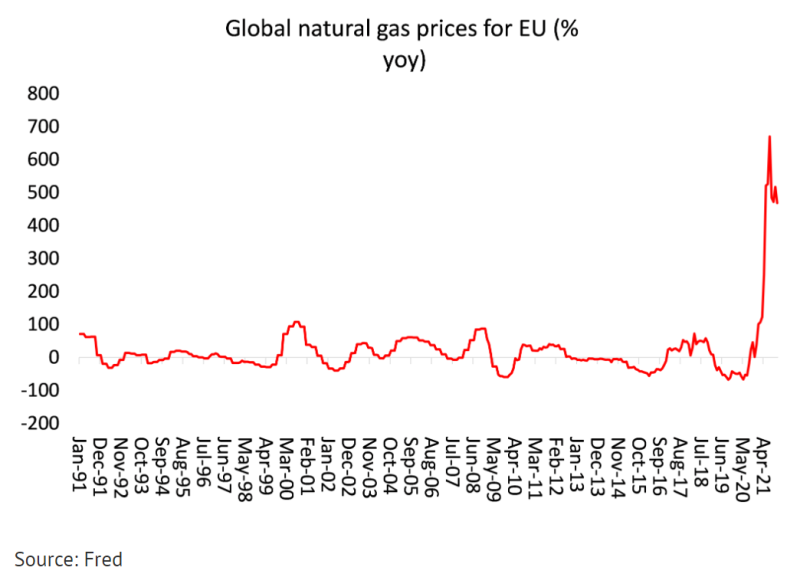

Nevertheless, perhaps there are signs globally down the road that inflation rates will ease at least during 2023. Crude oil prices are still 40 percent above a year ago, but prices have fallen from their peak of $120/b in June to $90/b. That should feed through to energy prices, at least for transport fuel. In contrast, natural gas prices are at all-time highs. This is particularly bad news for Europe, which depends heavily on gas imports from Russia.

The EU is trying to impose sanctions (including energy sanctions) against Russia over the invasion of Ukraine. But that means searching for new sources of supply, the competition for which globally is driving up prices. A combination of tight supplies and soaring demand amid persistent heatwaves across Europe (including a historic drought triggered by an arid summer that set heat records across Europe), threatens to halt energy shipments along the Rhine River while limiting hydroelectric and nuclear power production. At the same time, Russia’s Gazprom keeps reducing flows through the Nord Stream pipeline (now down to roughly 20 percent of its capacity), citing issues with turbines. So energy prices in Europe could rise even further as winter approaches.

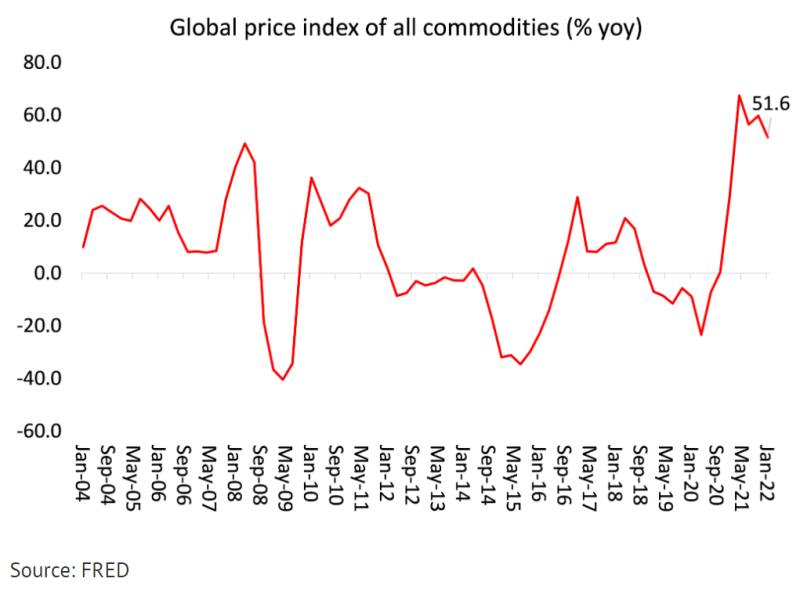

The other driver of inflation has been food. And here at last global food prices have dropped from all-time peaks, particularly after the agreement brokered between Russia and Ukraine to allow grain shipments through the Black Sea to world markets. But commodity prices in general remain over 50 percent higher than this time last year.

And that other key driver of global inflation, post the COVID slump, supply chain blockages, caused by lockdowns, loss of staff, lack of components and the slow regearing of transport logistics, is finally showing some easing. Even so, the New York Fed global supply chain pressure index (GSCPI), that measures various indicators of container ship and port blockages, is still much higher than before the COVID pandemic began.

And take all this evidence of moderating inflation with considerable caution: for at least three reasons. The first is that central banks have no control over the pace of inflation because rising prices have not been driven by ‘excessive demand’ from consumers for goods and services or by companies investing heavily, or even by uncontrolled government spending. It’s not demand that is ‘excessive,’ but the other side of the price equation, supply, is too weak. And there, central banks have no traction. They can hike policy interest rates as much as they deem, but it will have little effect on the supply squeeze. And that supply squeeze is not just due to production and transport blockages, or the war in Ukraine, but in my view, even more so to an underlying long-term decline in the productivity growth of the major economies.

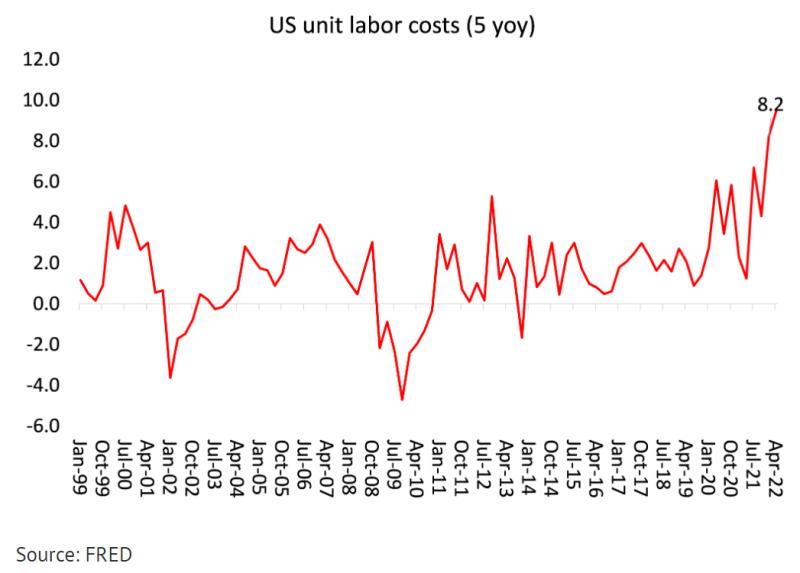

So the second reason for not expecting a sharp fall in inflation rates is that productivity growth has slowed so much that the supply-side cannot respond adequately to the recovery in demand for goods and services as economies came out of the COVID slump. For example, US productivity of labour (output per employee) has taken a huge tumble in the first half of 2022, down three percent over two quarters, the biggest half-yearly fall since records began.

Official figures tell us that US employment is rising. But at the same time, the latest US real GDP figures show that national output fell in the first half of this year. That is the arithmetical reason for why US productivity has fallen. But the underlying causal explanation is to be found in the long-term tendencies in the US economy; and not just there, but in most of the major economies.

The key to sustained long-term real GDP growth is high and rising productivity of labour. But productivity growth has been slowing towards zero in the major economies for over two decades and particularly in the Long Depression since 2010. US labour productivity growth is now at its weakest for 40 years. Indeed, before the COVID pandemic, the world economy was already slowing down towards a slump after ten years of a Long Depression.

The productivity crisis is driven by two factors: first, slowing investment growth in productive (i.e. value-enhancing) sectors compared to unproductive sectors (like financial markets, property and military spending). As a percentage of GDP, US productive investment has steadily fallen, both in net private and public civilian investment.

And second, behind this decline in productive investment is the long-term decline in the profitability of such investment compared to investing in financial assets and property. Profitability of investment in the main value-creating sectors is near post-1945 lows.

That brings me to my third reason for caution on inflation subsiding: the risk of increased wage demands driving up prices. When productivity growth is low, even small wage rises demanded by employees can sharply raise employee costs per unit of output. Companies are then forced to take a hit on their profits and/or try to raise prices to compensate. A so-called wage-price spiral could ensue. At least that’s the claim of the mainstream theory.

So far, that has not happened. And the mainstream economics charge that wage rises are causing the current inflation acceleration or even that future wage rises will do so is not backed by evidence historically.

Instead, average real wages have been falling sharply. The IMF reckons that the average European household will see a rise of about 7 percent in its cost of living this year relative to what was expected in early 2021. Employees everywhere are now trying to restore living standards through wage rise demands, in Europe and the US. If they are successful, this will most likely lower profits. Already, after reaching all-time highs, US corporate profit margins have begun to fall.

That means the major economies could enter a period of stagflation, not seen since the late 1970s, where inflation rates stay high, but output stagnates. Indeed, it could be worse than that. The risk of an outright global slump is rising. If central banks continue to hike their policy rates, all that will do is increase of cost of borrowing for consumers and companies, driving weaker companies into bankruptcies and suppressing demand across the board. Sure, that may finally reduce inflation but only through a slump.

The recovery from the COVID slump of 2020 has petered out. The world economy is teetering on a slump according to the latest data by JP Morgan economists. Their measure of global economic activity (global PMI output) has slipped to 50.8 (anything below 50 is a recession), which is a 25-month low. JPM say that the 50.8 measure is equivalent to a world economic growth rate of just 2.2 percent. That’s near ‘stall speed’ and remember includes China, India and other large economies. The global manufacturing sector is on the cusp of contraction and the services sector is slowing fast.

As the IMF puts it, “The global outlook has already darkened significantly since April. The world may soon be teetering on the edge of a global recession, only two years after the last one.” says the IMF in its latest economic forecast. The IMF has reduced its forecasts for global economic growth. Under its baseline forecast, the IMF now expects world real GDP growth to slow from last year’s 6.1 percent to 3.2 percent this year and 2.9 percent next year (2023). This forecast slowdown from 2021 to 2022 is the biggest one-year drop in economic growth in 80 years! “This reflects stalling growth in the world’s three largest economies—the United States, China and the euro area—with important consequences for the global outlook.” At the same time, the IMF forecast for the inflation rate has been revised up. Inflation this year is anticipated to reach 6.6 percent in advanced economies and 9.5 percent in emerging market and developing economies and is projected to remain elevated longer.

And these are the baseline forecasts for growth with the risks “overwhelmingly tilted to the downside.” There is a risk that “inflation will rise and global growth decelerate further to about 2.6 percent this year and 2 percent next year—a pace that growth has fallen below just five times since 1970. Under this scenario, both the United States and the euro area experience near-zero growth next year, with negative knock-on effects for the rest of the world.”

It will be even worse in the so-called developing countries: “many countries lack fiscal space, with the share of low-income countries in or at high risk of debt distress at 60 percent, up from about 20 percent a decade ago. Higher borrowing costs, diminished credit flows, a stronger dollar and weaker growth will push even more into distress.” The share of emerging market bond issuers with yields above 10 percent is now higher than at any time since 2013.

Recession fear is now at levels worldwide last seen in 2020.

At the very least, global inflation rates are still likely to be much higher than before the COVID pandemic by this time next year—and at the worst, the global economy could have entered a new slump only three years from the last one.

Michael Roberts is a Marxist economist based in London, England. He is the author of several books including The Great Recession: A Marxist view (2009), The Long Depression (2016), and Marx 200: A Review of Marx’s Economics 200 Years After His Birth (2018).