Who is considered an expert? News reporting on drugs must do better

Changing the narrative around drug use is the first step in affecting real policy change

According to Rebecca Hume and Katharina Maier, centring the voices and lived experiences of people who use drugs (PWUD) as well as the insights of harm reduction and public health advocates can go a long way in improving drug-related news coverage. Photo by Dan Toulgoet.

Across Canada, drug-related deaths continue to soar as the COVID-19 pandemic rages on. If there was ever any doubt before, the need for a strong, non-stigmatizing public health and welfare response to drug use should be urgently clear by now.

A key step toward such a response involves centring the voices and lived experiences of people who use drugs (PWUD) as well as the insights of harm reduction and public health advocates in drug-related news coverage.

As it stands, however, mainstream news often relies on the perspectives and information provided by our most powerful institutions—specifically police and law enforcement—in reporting on drugs. This continues despite the dramatic shift in public consciousness over the last year about the role of police in our society more broadly.

But shifting perspectives is no easy task because news media has immense power to inform public discourse about PWUD. Simply put, we urgently need coverage that gives space to the most marginalized folks in our society in order to humanize decades of drug policy failures. This would go a long way in an effort to change attitudes about drug use during the worst public health crisis in a century.

Take Winnipeg’s local news reporting for example. Based on an analysis of local news coverage of meth use in Winnipeg between the years 2004 and 2019, we found that drug users were cited in only nine percent of meth-related news stories. In stark contrast, however, police appeared in well over a third of all articles (39 percent), making them the most frequently cited source in our sample.

The reliance on police sources in news reporting on meth means that coverage is often framed in terms of crime and criminality—indeed, our analysis shows that 45 percent of stories directly associated meth with crime. This is a problem because the broader public then understands meth use as an individualized criminal-legal issue rather than the result of systemic and policy failures that require immediate funding and support from public health institutions.

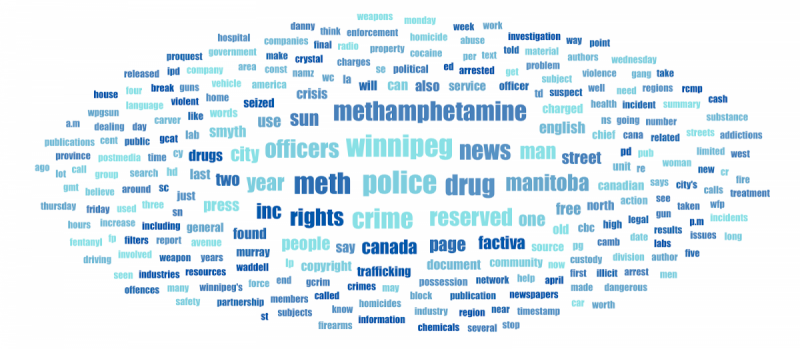

This word cloud was created based on results from the authors’ media analysis of meth in Winnipeg from 2004 to 2019. Supplied by the authors.

Why are police considered the experts?

There are a number of reasons why media outlets rely so heavily on the perspectives offered up by police departments when reporting on drug use.

First, law enforcement organizations have the institutional power and resources to provide journalists with press releases and statistics on crime. At a time when news agencies employ fewer reporters and are forced to make do with smaller budgets, access to this kind of pre-packaged information, which can be easily cited in news reporting, is ideal. Moreover, from the perspective of the media, the police are reliable, authoritative, and credible sources ready to supply a constant stream of crime stories for daily reporting.

Conversely, for the police, the media present an essential outlet through which to manage their public image and legitimacy. In a year of historic anti-police organizing, managing the public relations of this particular institution has never been so important.

Police-dominated coverage of drug use, however, provides only a limited, one-dimensional perspective on the issue and neglects the voices of those most affected by substances like meth while minimizing how their experiences are shaped by current drug policies.

The consequences of police-saturated news coverage have real-life impacts on PWUD: as long as police continue to be so heavily relied upon in news reporting on meth, mainstream narratives about drug use will inevitably remain inextricably connected to criminality. This further justifies police intervention as the appropriate response to supporting PWUD (and the budgets necessary to do so).

More from the real experts, please

Mainstream media has the ability to shift this narrative from one rooted in criminality to one that approaches the issue of drug use as a public health and welfare issue based on people’s experiences and lived realities. This can be done by seeking information from non-police and non-government sources, and in particular, from the experts themselves: PWUD.

Centring the voices of PWUD is an essential first step in drawing attention not only to people’s lived experiences with drug use, but also, importantly, to the ways in which those experiences are formed, shaped, and harmed by forms of racism, marginalization, exclusion, and structural violence that often accompany police intervention. This is what balanced coverage looks like.

In addition to PWUD, local news should also draw on the insights of harm reduction and public health professionals and advocates in their reporting. The Manitoba Harm Reduction Network (MHRN), Sunshine House, and Central Neighbourhoods are just a few of the many authoritative sources for information related to drug use in Winnipeg.

If provided with proper funding and other resources, organizations like these could provide the media with a regular stream of information similar to the methods of the police. MHRN even has a media toolkit titled “How To Talk About People Who Use Drugs.”

Citing PWUD and community organizations like these are essential in reframing the mainstream narrative away from crime and criminality towards an inclusive, non-punitive, and non-pathologizing lens that centres harm reduction, autonomy, and community wellness.

Speaking to drug users and harm reduction advocates as experts in the field would go a long way towards normalizing and validating their voices as authoritative, and rightfully so. Changing the narrative around drug use is the first step in affecting real policy changes.

We simply cannot wait any longer.

Rebecca Hume (she/they) is a settler living on Treaty 1 lands, the homeland of the Métis Nation. She is a freelance researcher and community organizer in so-called Winnipeg. You can find her on Twitter @rebshume.

Katharina Maier is an Assistant Professor of Criminal Justice at the University of Winnipeg. She studies issues around punishment, penal supervision, public health, and crisis.