When we were young

Radicals recount early experiences that shaped their political lives

JOHN CLARKE, organizer, member of the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty

Neither of my parents had any major interest in politics, but they were both deeply affected by the hardships of working-class life as they grew up in the 1930s and ’40s in London, England. At the end of the Second World War, my Dad went absent without leave because his mother was dying and the army would not relent on a decision to post him to the Far East. For this he was sent to Colchester Military Prison, an experience that he never entirely got over. When I was about seven, my parents took me to Blenheim Palace, family seat of the Marlboroughs and birthplace of the infamous imperialist, racist and mass murderer, Winston Churchill. We visited the birth room of this “great man” and, seeing such an incredible display of wealth, my Dad leaned over and said to my Mum, “Blimey, if I’d been born here, I would have wanted to fight for my country.” Somehow, those words and the way he said them burned themselves into my memory. The Old Man didn’t know it, but he planted a seed that day.

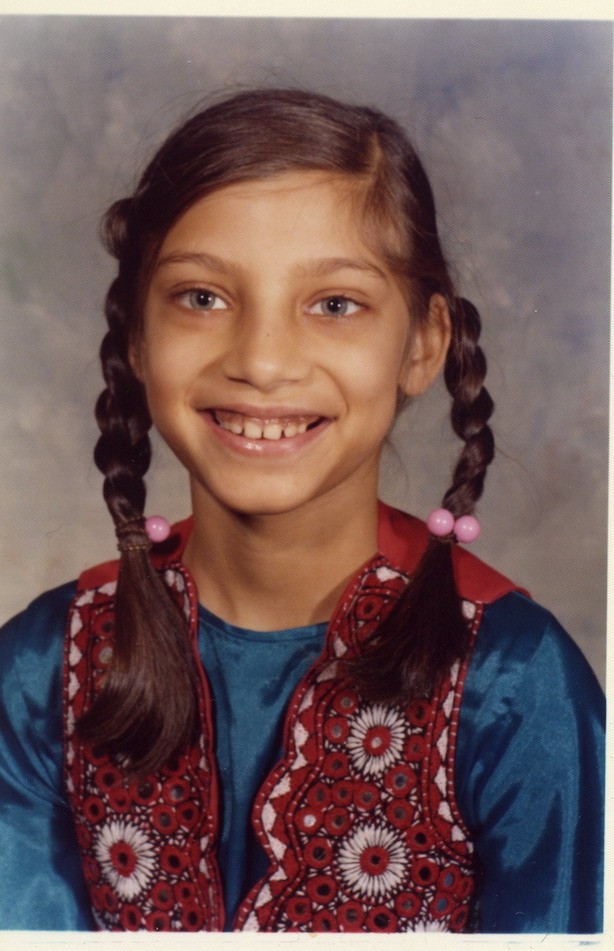

Portrait of a radiant Ummni Khan at

age nine.

UMMNI KHAN, legal theorist, author of Vicarious Kinks: S/M in the Socio-Legal Imaginary

I have older sisters, and when we were kids, they usually decided what music to play. Sometime in the early 1980s, my eldest sister brought The Stranger home by Billy Joel, and played it on our Fisher Price stereo (I know they make toys, but they made real record players too). She thought the album was good, but I became obsessed with the title song. When I had the bedroom to myself, I would listen to it over and over, carefully picking up the needle to start it from the beginning as soon as it had finished. It begins with Joel’s signature piano playing, followed by a casual whistling sequence. And then the tune suddenly shifts into this rougher, grittier mood. The lyrics talk about how a stranger lives in us, who may be “satin” or “steel” or “silk” or “leather.” We hide secrets from our lovers, yet one day, we may confront a “stranger” in bed, or allow our own alter ego to materialize. I didn’t know what BDSM was at the time, or sexual fetishes, or anything of that sort. I was only, like, 10 years old. But the song struck a chord with me. I felt recognized, exposed, aroused each time it played. The lyrics opened my eyes — technically my ears — to the possibility of erotic variation, of kink, of, in Gayle Rubin’s words, “benign sexual difference.”

CY GONICK, publisher of Canadian Dimension

When I was about 10 years old — just after the end of the Second World War — I asked my mother why people weren’t able to just go into a store and take whatever they need. She smiled and told me that our system doesn’t work like that. About two years later, I saw some kids playing in a yard while we were visiting my grandmother in Winnipeg’s North End and I asked my mother what they were up to. You have to understand that she was always concerned that I was a loner. On this day, I think she sensed an opportunity. “You see those kids across the street,” she said. “They meet there every Sunday and they talk about the question you asked me a couple of years ago…. There is a place in the world,” she continued, “where people give according to what they are capable of giving and take according to what they need. And that place is a called a kibbutz. If you want to learn more about it you can go over there and join those kids.” I was terribly shy, but I went over anyway and they immediately placed me in a group. Fortuitously enough, my group leader was a young gung-ho university student who was very keen on getting us boys to read. He directed us to socialist novels — Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, Jack London’s The Iron Heel — and I sought them out at the library and read them. They had an enormous impact on me and so did our leader. At one discussion, I even remember him giving an impromptu lecture on the labour theory of value. Of course, the organization itself was a social-democratic labour Zionist youth organization, not radical. But in a way, those experiences kind of directed me for the rest of my life.

GEOFF BERNER, musician, author of Festival Man

My parents were pretty left-wing in the ’70s. Then in the ’80s, they changed their minds and supported the Socreds. That was their perspective and as a young teenager I shared it. I even volunteered for the Tory Bill Clark’s campaign against John Turner in Vancouver Quadra in 1984. We lost. Turner won his seat out of pity. Then, when I was about 14 or so, I sneaked into the Vancouver Folk Festival because I was in love with a girl who was there. I wandered in front of Stage Four. Billy Bragg began playing. He played “The World Turned Upside Down,” by Leon Rosselson, or “The Diggers Song” as it’s also known. One song changed everything. I’ve never been the same. I went from right to left in four minutes. It’s probably the reason I’m a singer-songwriter, too. I know songs can change people because it happened to me.

SHARMEEN KHAN, organizer, editor of Upping the Anti

I was born and grew up in Regina, Saskatchewan, at a time where there weren’t many Pakistanis — or that many immigrants or refugees of colour. My family settled in a predominantly white area and was set on integrating with the white folks as much as possible. So my earliest memories is always wanting to be white. I was one a few students of colour in my elementary school and in high school, and I remember hiding that I was Muslim and pretending to be Christian. I wished my name didn’t scream so much South Asian-ness. I experienced a lot of violence in the home and outside of the home. And to prevent this violence — I just tried to conform as much as possible and please the people that were hurting me — whether it was a teacher or my father. But it’s hard to conform to something that you have no power to change. When I was eight, I started drinking a glass of lemon juice a day because a classmate told me it helps lighten pigment. I wore long sleeved shirts in the prairie sun so I wouldn’t get any darker. At home when my parents made me pray to the Muslim god, I would pray that I could wake up the next day to be white. When I prayed to the Christian god in school, I would pray the same thing. I guess I thought doubling up on Abrahamic gods would give me an advantage. There is no clear moment or immediate shift as to when I became political or when this all ended in that “aha” moment. I guess there was this point of sheer exhaustion of wanting to change something I couldn’t. And at that point, I was getting into the small but influential prairie punk scene and a teacher lent me Alex Haley’s biography of Malcolm X. I didn’t have a historical connection to either of those things, but after finishing the book and rushing to an I-Spy show, I began to feel the excitement of learning the language to understand a small piece of my world. And that other people also experienced it, obviously with a lot of differences. That exhilaration and feeling of connection is what I try to keep going when trying to learn and organize. Today, I get as dark as I can in the summer sun as a big “fuck you” to white supremacy.

JANET STONEFISH, Delaware, advocate with Native Child & Family Services of Toronto

I lived a life in isolation as I could not allow myself to feel the love that I once took for granted. As a nine-year-old Delaware child, I was placed in a Native residential school for five years. The loss and separation from my mother felt like I lost a part of myself. I lived my life half existing and hoping the love that was once so pure and real would one day return. My suppressed anger felt like I was screaming; “Bring back my mother or I will never talk to anyone again.” And I didn’t as I noticed no one was interested in returning my mother; but I remained lost without her. Unfortunately, as an adult this laid down a path of troubling relationships along with the predictable neglectful parenting of my three children. Most of my life was about survival and trying to make sense of how and why things never seemed to work out. Reconnecting to this experience has led me to work in a world with children and mothers, with the intent of letting them know that I understand and am willing to listen because I care.

SAKURA SAUNDERS, editor of ProtestBarrick.net, Beehive Collective member

Surprisingly, the political discussions that I had growing up with a right-wing father were the childhood experiences that contributed the most to my activist development. I remember him cutting out articles from The Economist about livestock subsidies, and that contributing to my decision to go vegetarian at age 14. Then, as I began to become more conscious of injustice in the world, I would bring him stories of the impacts of capitalism and globalization to see how he would react, but he would always dismiss them. I noticed that he would always rely on some simplistic theory: supply and demand, capitalism as a self-correcting system, the media highlighting exceptions to the rule, abuses happening only 1 per cent of the time. While I often felt that he was making up statistics to justify his bias, his dismissals challenged me to understand the issues. Anticipating my dad’s arguments, I started thoroughly researching issues before attempting to advocate for them. This clearly influenced my approach to politics. With protestbarrick.net, I take one company — Barrick Gold, the world’s largest gold miner — and evaluate it thoroughly, documenting its abuses in over 10 different countries with over a thousand articles. Today, even my dad (who staunchly defends capitalism) has come around on several issues. Of course, he might just be sick of losing arguments.

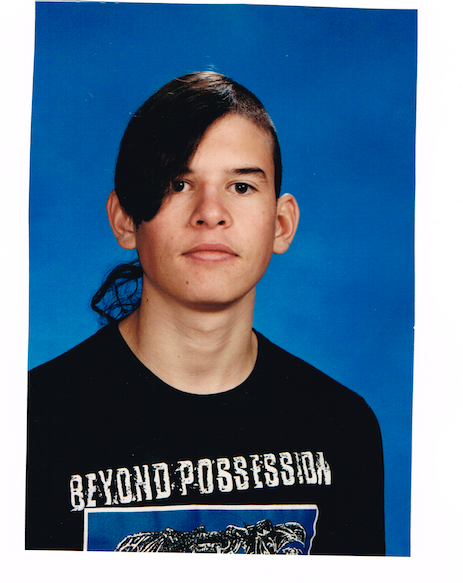

Tod Kowalski

as a teen,

sporting a

favourite t-shirt.

TODD KOWALSKI, musician, member of I-Spy and Propagandhi

When I was a kid I traded three KISS albums for the first Millions of Dead Cops (MDC) record and another two by the Exploited. I’d never really heard either of them, I was just taking a gamble. When I put on the MDC record, it blew my mind. The politics and the brashness were like nothing I’d ever heard before. There was a song called “John Wayne was a Nazi,” another called “Dead Cops” about police oppression, and another called “America’s so Straight?” about gay rights and being different. In junior high, I was listening to punk music but also still being a stupid little shit. It’s funny, I was trying to write these kind of anti-racist lyrics while I was still walking around being a total asswipe. But I guess I was starting to put it together that I didn’t really think society was alright and those records kind of put me on a different path. The next MDC record came with a giant poster that I put beside my bed. It was all politics. There was stuff about Nicaragua. There was an image of two young people who had had acid poured on their faces. I had that on my wall and I’d look at it everyday.

GARY KINSMAN, organizer, researcher, author of The Canadian War on Queers

I grew up in the middle-class suburb of Don Mills, Ontario. In school, I largely chose a strategy around masculinity of trying to be smart and intellectual. I did well at it, but I also found it remarkably unsatisfying. In that context, I started on a bit of a process “cerebral radicalization.” I read Fidel Castro and Che Guevara. I started to listen to Radio Havana Cuba on shortwave. But it was still all very intellectual. The first time I ever remember actually doing anything was after the War Measures Act was declared in 1970 and people were being rounded up. My homeroom teacher asked “what do those people in Québec want?” Somehow, I managed to put my hand up and said something, probably about national problems or social oppression. My teacher was quite taken aback that someone had actually tried to answer his rhetorical question. After that, I started to think more and more about how Castro and Guevara didn’t just read things but actually did things. I felt like I needed to start doing things too. One of the first events I went to was a rally at Convocation Hall organized in defence of Québec political prisoners. This would have been one my first trips downtown on my own. Robert Lemieux, a lawyer for the Front de Libération du Québec, as well as Michel Chartrand, who was then the president of the Montreal Council of the Confédération des Syndicats Nationaux, both spoke. It was a large rally, maybe 1,500 people, and midway through it was attacked by fascists! There was a big punch out. But I actually found it quite an exciting event. For the first time, I felt like I was part of something that was about more than just me as an individual.

This article appeared in the Spring 2016 issue of Canadian Dimension (Childhood).