What’s the point of voting NDP?

Lessons to learn for Jagmeet Singh from the German election

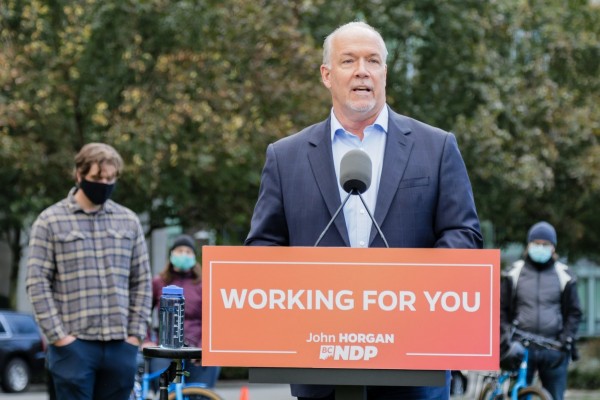

Burnaby South MP and federal NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh at a rally in Penticton. Photo by Brennan Phillips.

The joviality and popularity of its leader cannot hide the fact that the 2021 election was a big downer for the NDP. Despite a solid war chest, relentless campaigning, and promising polls, the party achieved a net gain of a single seat. In fact, its track record in the decade since the 2011 Orange Wave would by all traditional accounts be considered a straight-out disaster: 75 percent of its seats lost, stagnating for three federal election cycles at below 20 percent, and routinely underperforming on pre-election polls.

True, the NDP champions all the issues a clear majority of Canadians care about and support—from higher taxes on the rich to dental and pharmacare, to genuine reconciliation, to a radical rethink on the environment. In many ways the NDP is, or should be, the party of the day, but it consistently lacks the power to realize its agenda at the national level. Ultimately, voters elect a party for its ability to put campaign slogans into action, not for now and forever occupying the moral high ground.

Disappointment is spreading in the party since election night. At some point very soon the NDP’s more than three million voters will want to see results, get bang for their buck, tire of a party that seems to have forever settled on the consolation prize, and will start wondering what, strategically and politically, is the point of voting NDP? Not only can Jagmeet Singh and his campaign managers not give a convincing answer, they don’t seem to know themselves.

Blatantly self-defeating strategies

As has been frequently observed, the NDP plays by the rules of a game it knows full well is rigged against it. What is worse, like generals fighting yesterday’s war, it continues to play by these rules even though the game is changing in their favour before their very eyes.

It’s as obviously flawed as trying to hush up a prime minister’s surf holiday: Canada’s first past the post electoral system is specifically designed for a two-party system, preventing the likes of Jagmeet Singh from ever getting close, yet he keeps campaigning as if he had a real shot at 24 Sussex Drive. The head of even the most dewy-eyed NDP supporter tells her heart that 2011 was an outlier result which to repeat would require one of the major parties to implode or be led by Michael Ignatieff again. Regardless, Singh repeatedly aims for replicating Jack Layton’s singular feat—with humble restraint.

Despite the Liberals tirelessly belabouring the bogeyman of a vote for the NDP effecting a Conservative win in every election cycle, the NDP appears surprised by such left field nastiness each time, completely clueless as to effectively countering it. Even though majority governments are evidently becoming a thing of the past here (five out of seven elections in the 21st century resulted in a minority government), NDP strategists wholly fail to grasp how this changed environment should shape their narrative and campaign strategy. Another obvious factor is that smaller parties’ only chance at succeeding in a first-past-the-post system are bottom-up, localized electoral pacts with other small parties to facilitate tactical voting in key seats, yet Canada’s NDP and Greens, in a masochistic variation on Trotsky’s famous command, keep marching separately to end up being struck separately.

The list of blatantly self-defeating strategies and flawed tactics could go on, but one gets the picture: the NDP, while offering a powerful progressive agenda and the most popular leader, is hopelessly out of tune with the strategic requirements of a changing political environment and at a loss on how to capitalize on it. What is called for in this shifting landscape is a profound strategic re-orientation.

For instructive clues on what to do and what not to do the NDP would be well advised to direct its attention to the country that just held a federal election six days after Canada and experienced a political earthquake: Germany.

Lessons to learn from Germany

Since the Second World War Germany has been governed by one of two major parties, rarely in a majority government, occasionally in a grand coalition between the two, but more often than not in a coalition between one Volkspartei (party with the claim and self-image to represent the majority of the people) and a smaller party. In these coalitions the minor partner usually played the role of Mehrheitsbeschaffer (supplier of a majority), for which it was rewarded with a prestigious ministerial post and a few token concessions from its agenda. This, one could argue, is also the role the NDP played in the 43rd Canadian Parliament, though without getting anything in return.

Ten days ago, this duopoly of German politics that, like in Canada, had been eroding for a while, received a seismic shock. The Conservatives (CDU) who Angela Merkel had for 16 years led from victory to victory, with her no longer on the ticket, lost almost ten percent, bested by the Social Democrats (SPD) who experienced a miraculous resurrection after haemorrhaging support for almost two decades. The only reason the CDU’s hapless new leader, Armin Laschet, hasn’t been offed by his party yet, is the remote possibility that the victorious SPD might botch the ensuing coalition talks and that the CDU can limp back to the Chancellery through the backdoor.

The true winners of the election, though, are the Greens and the Free Democrats (FDP). At 15 and 11.5 percent respectively, they together gained more votes than either of the two Volksparteien and are now not only in a position of kingmaker but can de facto dictate the agenda for the next government. Without the two smaller parties no government can be formed in Germany now; they effectively gained a blocking minority. To be sure, to get Greens and the FDP (a liberal party whose leader loves to show off his vintage Porsche 911, more socially and economically conservative than Canada’s Liberals) on the same page on an eco-social market economy and the expiration of combustion engines in German cars is as challenging as getting Justin Trudeau and Celina Caesar-Chavannes to agree on the meaning of feminism. But the temptation of leading a transformation of the entire country and weakening the two major parties no doubt will bring Greens and FDP together.

Both grasped the historic opportunity voters had offered them on September 26, and right on election night took the initiative to start negotiating an agreement with which they then intend to hold the CDU and SPD ransom. Either the SPD’s Olaf Scholz signs on the dotted line whatever they serve up, or they move on with their accord to the CDU, who, with or without Laschet, will be all too happy to comply.

Election posters of the Social Democratic Party’s (SPD) candidate for chancellor, Olaf Scholz, Christian Lindner of the liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP) and Greens party co-leader Annalena Baerbock. Photo courtesy Reuters.

A few straightforward tactical steps and a communicable strategy

This is the commanding position the NDP should aim for in the next election: a blocking minority. This is what the party should communicate to voters from now until election day:

- The days of majority governments in Canada are a thing of the past;

- Canadians no longer want to reward a single party with absolute power, but expect parties to collaborate as partners for the better of the country;

- That’s the point of voting NDP, to once and for all change the political culture in Canada, to realize a progressive government by forcing it upon the Liberals (as a reform government is now forced on the sclerotic SPD or CDU in Germany).

The goal of a blocking minority should become core to the party’s DNA. Any political analyst would advise the NDP that this is its best hope. Why not openly communicate that goal to its voters then? Why not treat Canadians as mature enough to handle the truth? In fact, Jagmeet Singh should open his closing statement at the next leaders’ debate with the statement, “Look folks, I’ll be straight with you here. I’m not going to be the next Prime Minister of Canada. But I don’t have to be. If you vote NDP, I can guarantee that we’ll get done what’s in our program, we can ensure a progressive government for this country.”

That argument would take the wind out of the Liberals’ sails in scaremongering that a vote for the NDP would precipitate a Conservative victory. The NDP could hold against it that even if the Conservatives win a plurality, it wouldn’t matter. Every seat shifting from Liberals to NDP would be a net gain for the progressive government; even with the Liberals losing more than 30 seats, if the NDP gains a blocking minority, they can see to it that the next prime minister is a Liberal, conditional on her agreeing to adopt most of the NDP’s program.

Jagmeet Singh should stop trying to emulate Jack Layton, aiming for a seat count that is impossible to achieve in the current constellation. Here too, a lesson can be learned from the German election. The Greens aimed too high and abandoned the two-headed leadership of Annalena Baerbock and Robert Habeck that had served them so well for years and instead went into the election with a single leader, touting their ambition to become a Volkspartei themselves. They dropped from 28 percent in the polls in March to half on election night (they still almost doubled their tally since 2017). The FDP, on the other hand, stuck to their realistic goal of a double-digit result and got rewarded for it.

The next step ought to be a progressive pact between Greens and NDP to facilitate tactical voting in two dozen key seats. The NDP can offer to back off in Saanich–Gulf Islands, Kitchener Centre and perhaps another seat, in exchange for the Greens endorsing the NDP in 20 seats in British Columbia and beyond. Such a local deal, for example, would have made all the difference for the NDP in Vancouver-Granville two weeks ago. If even Greens and the FDP in Germany can form a coalition, striking an accord between NDP and Greens should be attainable, all the more since the Greens are currently engaged in a process of self-cannibalization and can consider themselves lucky to be on the ballot in the next election.

To be sure, Germany has an electoral system that is more democratic—which is why electoral reform reproducing the German system was recommended for Canada by the House of Commons Special Committee on Electoral Reform in 2016. Unlike the Alternative Vote system favoured by Justin Trudeau that would skew election results even further for the Liberals, the German system makes it easier for smaller parties to gain seats, and the NDP should make electoral reform the first bill the new progressive government passes. That would automatically double its seats and cement its role as the indispensable power broker (and the Greens would benefit even more from it, which might make them more amenable to an alliance with the NDP). But even in the current Canadian electoral system, all it takes for a blocking minority is for the NDP to gain 40 or more seats. That’s less than they had in 2015, that’s an achievable goal, and more importantly, an easily communicable strategy.

Instead of playing the game by the Liberals’ rules, the NDP should be straight with its voters: get us to 40 seats and we’ll get you a fairer tax system, a green economy, meaningful reconciliation, dental and pharmacare and electoral reform on top of it all. What is more, an NDP blocking minority would change Canadian politics for good, as it has the potential of transforming its political culture, making it less divisive and more democratic and collaborative. This is a winning narrative, a narrative the whole country can get behind—it is what Canadians have signalled over and over again they want Ottawa to be.

Hannes Černy is an Assistant Professor of International Relations at Northumbria University in the United Kingdom, where he works on sovereignty, statehood, and ethno-nationalist conflict. There he is the founding Director of an MA Program in International Relations, Conflict and Security at the Newcastle and Amsterdam campuses. He has also taught at other UK universities and in Germany, at Mount Allison University in Canada and at the Central European University, a private liberal arts institution of higher education that was forced out of Hungary by nationalist strongman Viktor Orban. Follow him on Twitter @HannesCerny.