US sanctions on Venezuela are deadly—and facing mass resistance

Average Venezuelans understand that US sanctions hurt them, and should be resisted

Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. Photo from Flickr.

Venezuelan centrist Claudio Fermín was a protégé of neoliberal president Carlos Andrés Pérez in the early 1990s—and, at first, a firm opponent of Hugo Chávez. But like some others in the same political camp, in more recent years, he has changed course. Particularly since Donald Trump imposed sanctions on Venezuela, Fermín has become outspoken in vehemently opposing both US interventionism and his own nation’s radical right.

Such a change shows just how much Venezuelan politics have been transformed in the recent past. Since the attempted coup of April 2002, the country’s leftist governments have been pitted against a united opposition, intent on achieving regime change by any means possible. But now, such extreme polarization seems to be weakening.

A former mayor of Caracas and presidential candidate, Fermín is not alone among centrist politicians in bucking the Trump administration’s insistence on a boycott of the December 6 National Assembly elections, in a bid to further isolate president Nicolás Maduro.

Fermín’s nationalistic rhetoric was on display in an interview last month, as he lashed out at the Venezuelan right, the Trump administration, and the other governments that have followed its lead: “The superpowers have buddied up with the nation’s anti-Venezuelan political elite, who don’t really have Venezuela in their hearts, who impede the arrival of oil tankers with much-needed gasoline … The sanctions are a negation of national sovereignty.” Washington’s implementation of international sanctions—opposed by dissidents within opposition ranks—has greatly contributed to this shake-up of Venezuelan politics.

Even in recent years, the opposition had been united. In the 2015 elections for the National Assembly, it achieved an all-encompassing unity, supporting a single anti-government ticket that emerged victorious. Then, in January 2019, the entire opposition went along with Juan Guaidó’s self-proclamation as president. But now the centrists, who for the most part recognize the legitimacy of the nation’s political system, are faced off against politicians on the Right who are calling for abstention in the National Assembly elections slated for December 6.

The convergence between center and left is not only the result of Washington’s policies and the untold suffering they have inflicted on the Venezuelan people. It is also the product of president Nicolás Maduro’s adroit strategy of accepting some of the demands of the centrists while pursuing a hard-line approach against the insurgent opposition. Carlos Ron, vice-minister for North America, told me, “Maduro has to be recognized for achieving what appeared impossible: moving a big chunk of the opposition from insurgency to peace.”

But this strategy also has its downsides. Concessions to business interests, which go hand in hand with Maduro’s conciliatory strategy, have been criticized by a left faction of the governing Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela (PSUV). In addition, the Communist Party and several other parties and groups belonging to the ruling Polo Patriótico alliance have broken with Maduro and formed a rival slate for the upcoming elections.

And despite their recent stands, it is clear that the centrists are far from stable allies for Maduro. Some are just biding their time—waiting for the right moment to attempt to force him out through a recall election.

Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaidó. Photo by Jonas Pereira/Agência Senado/Flickr.

Stiffening the sanctions

As the Trump administration rachets up the sanctions and threats of military action, Venezuelans increasingly reject them. The public opinion firm Hinterlaces released a poll in November 2017 indicating that 72 percent of Venezuelans oppose the sanctions, and another in August 2020 showing that the figure had increased to 81 percent. According to this latter survey, 80 percent of Venezuelans say that the “role of the United States has been negative.”

Trump’s stiffening of the sanctions in the age of COVID-19 is a premier example of what Naomi Klein calls the “Shock Doctrine”: situations of crisis and suffering provide the powerful with unique opportunities to impose dramatic changes.

In the midst of the coronavirus, the Trump administration has ordered four oil service companies to close operations in Venezuela. It is also rescinding similar special “permissions” that had been granted to Spain’s Repsol, Italy’s Eni, and India’s Reliance Industries to engage in swap arrangements involving oil, as long as no cash was involved. The termination of these barter deals will deprive Venezuela of diesel fuel used to transport food and generate electricity.

The sanctions against individual Venezuelans have also taken a disturbing turn in recent months. Previously, the targets were Venezuelan politicians, bureaucrats, and others associated with the government who were accused of engaging in illicit acts, such as corruption, repression, and drug trafficking. But now, in 2020, even political centrists are in the crosshairs of the Trump administration, because of their insufficient enthusiasm for Guaidó.

In January, the Department of the Treasury sanctioned seven dissident members of the opposition’s main political parties—Acción Democrática (AD), COPEI, Primero Justicia and Voluntad Popular—who had begun to question their organizations’ unconditional support for Guaidó and opposition to electoral participation. The Trump administration took at face value the word of pro-Guaidó leaders that the dissidents were engaged in corrupt dealings involving a government food distribution program. In fact, the sanctions were politically motivated, as revealed by James B. Story, US ambassador to Venezuela, when he warned “those who undermine Venezuelan democracy will be sanctioned.”

In September, Steven Mnuchin and the Treasury Department made it even clearer that the sanctions were all about politics. The heads of five break-off parties including AD’s Bernabé Gutiérrez, a well-respected longtime party leader, were placed on the sanction list. In doing so, Treasury accused these “key figures” of carrying out a plan “to place the opposition parties in the lap of politicians affiliated with the regime of Nicolás Maduro.”

In adopting punitive measures, the Trump administration is taking sides in an internal party matter of tactics. Indeed, the dispute within different parties of the opposition, particularly AD and Primera Justicia, over electoral participation versus abstention dates back many years. Gutiérrez questioned his party’s refusal to run candidates in the National Assembly elections of 2005, when Claudio Fermín was expelled from AD for advocating participation.

How marginal are the centrists?

Parties on both sides of the political spectrum have split in the lead-up to the December elections. In the case of AD, COPEI, Primero Justicia, and Voluntad Popular, the PSUV-dominated Supreme Tribunal of Justice has recognized the legality of the parties participating in the electoral contest, and not the abstentionist ones.

The Trump administration has labeled the non-abstentionists “marginal politicians.” If the presidential elections of 2018 are any indication, abstention will be just slightly over 50 percent. Naturally, that does not mean that all those who abstain are thereby supporting Guaidó and his allies.

Much is at stake in the battle between the abstentionists and non-abstentionists. The emergence of a bloc of non-leftist parties that either explicitly or tacitly recognize the legitimacy of Venezuela’s political system could pave the way for a new era in the country’s politics devoid of the internecine warfare of the past. Furthermore, it is a clear demonstration of the bankruptcy of the Trump administration’s regime change efforts. And it puts the lie to the claim of both Democratic and Republican leaders that Maduro is nothing less than a dictator.

Fermín argues that opposition party militants are at cross-purposes with their leaders. “Thousands of activists have been denied the possibility of running for city council or for mayor. Abstentionism has castrated a whole generation of activists since 2005.”

Gutíerrez claims that in January, AD’s state-level secretary-generals held rank-and-file assemblies at the local level and “everyone expressed support for electoral participation.” Subsequently, however, national secretary-general Henry Ramos Allup imposed his will on the party in favor of abstentionism.

Fermín and Gutiérrez may be overly optimistic regarding their projections for the turnout on December 6. The nation’s harsh economic conditions, in contrast to its previous status as a privileged, oil-producing nation, influence many Venezuelans to doubt the legitimacy of the existing system. Furthermore, the sway of opposition parties that favor abstention cannot be overestimated.

Not only AD but also two-time presidential candidate Henrique Capriles of Primero Justicia had been open to electoral participation early this year, but then swung over to the abstentionist camp. Undoubtedly, pressure from abroad, including fear of US sanctions, does much to explain their reconsideration.

Indeed, the international setting is a key variable. Most of the governments in the Americas and Europe are in the hands of right-wing and conservative parties and have played an activist role in favor of Venezuelan regime change. The Venezuelan centrists hoped for backing from Europe, particularly Spain’s moderate government, which at one point sent out mixed signals. But much to the disappointment of the centrists, in September, the European Union rejected Maduro’s invitation for it to provide electoral observers in December.

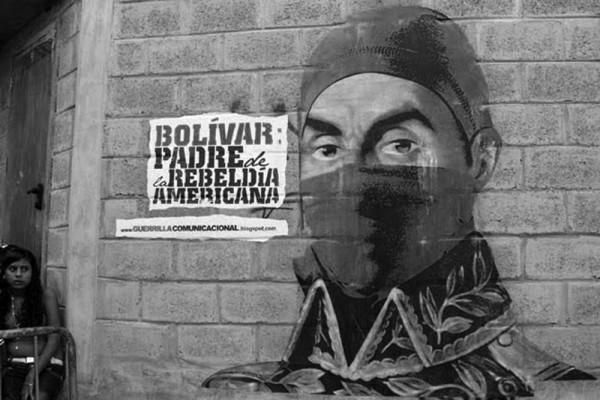

Mural depicting Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. Photo by Joka Madruga/Flickr.

Maduro’s gambit

The Maduro government and the centrists have supported each other in concrete ways. In January, the centrists requested and received legal recognition from the Supreme Tribunal of Justice for the National Assembly they controlled, as opposed to a parallel body controlled by Guaidó’s followers. Then, the same court recognized the centrist-controlled parties that had split off from the ones headed by traditional opposition leaders. In turn, the centrists have explicitly or tacitly rejected the Right’s characterization of the Maduro government as a narco-terrorist dictatorship.

Indeed, the centrists’ willingness to defy international and domestic pressure is predicated on three assertions: first, the Maduro government is not a narco-state, second, it is not a dictatorship, and third, it has over the recent past adopted business-friendly policies.

If convincing evidence were to disprove any of these statements, the strategy followed by the centrists would be untenable.

Maduro’s pro-business reforms were welcomed by centrists—but brought criticism from some on the Left, including close supporters. The latest example of the government’s opening to the private sector is the recently passed “Anti-Blockade Law,” which would allow the executive to enter into secret agreements with private capital over new property arrangements—possibly containing “clauses to protect investment in order to generate confidence and stability.”

The Communist Party slammed the arrangement as a reversal of Hugo Chávez’s policies in favor of national independence and an attempt to legalize a “policy of subordination to the interests of capital.”

Fermín was more receptive to the proposal and praised Maduro for not expropriating a single company, which he claimed amounted to a “self-criticism” with regard to the policies of his predecessor.

The second assertion—which debunks the narco-state thesis—denies the existence of the drug-trafficking “Cartel de los Soles,” which Washington has been claiming is operated by the Venezuelan heads of state ever since Chávez was elected in 1998 and is now led by Maduro. Coincidentally, the US Justice Department waited until this March to introduce an indictment in federal court in Manhattan the same day the Trump administration put a $15 million bounty on Maduro.

Fulton Armstrong, with decades of experience working for US intelligence, has said, “No serious analyst I know outside of the government would say there is a Cartel de los Soles.”

The third claim—that of dictatorial rule—is equally far-fetched but calls into question Maduro’s hard line against adversaries. The decision to recognize centrist-led parties instead of traditional opposition leaders, for instance, appears heavy-handed. Maduro defenders may respond that those leaders have cast themselves so far outside of the law by actively supporting foreign intervention and so many violent, regime-change actions that they have, at least temporarily, forfeited their democratic rights. But this argument cannot be applied to leftist parties such as Patria Para Todos (PPT) and the Tupamaro—who, after leaving the governing Polo Patriótico alliance (along with the Communist Party), lost their legal recognition, which was handed to split-off organizations. At the same time, the PSUV’s mayor of Caracas made false accusations regarding the moral conduct of PPT secretary-general José Albornoz.

Government critics point to irregularities and violation of democratic norms, such as the Supreme Tribunal of Justice’s recognition of certain political parties and not others. But most critics seldom present concrete plausible evidence of votes not being counted correctly, surely essential to defining the government as a dictatorship. Electoral fraud is frequently conflated with irregularities, as was the case in the two previous presidential elections of 2013 and 2018. Labeling Maduro a “usurper,” as the opposition repeatedly does, is predicated on the assumption that electoral fraud was committed in both elections.

Luis Vicente León, a much-respected pollster and supporter of the opposition, argued that the essence of democracy is a state that provides “the same conditions for all actors, in which the arbitrator should be impartial … and public resources not be used in favor of anyone.” León is right to say that this golden rule is being violated—though to some extent it always has been, ever since the outset of Venezuelan democracy.

Carlos Ron points out that, at least in one respect, the playing field is tilted in favor of the opposition. “The voter knows full well that by reelecting the PSUV, the sanctions stay in place. The minute the opposition returns to power, they’ll be lifted.” That one factor alone is likely to sway a lot of votes in December.

Steve Ellner, a retired professor at Venezuela’s Universidad de Oriente, is an associate managing editor of Latin American Perspectives and editor of the forthcoming book Latin American Extractivism: Dependency, Resource Nationalism, and Resistance in Broad Perspective.

This article originally appeared in Jacobin.