Trust us? Whether it’s government or media, you have simply got to be kidding

Public relations consultants now outnumber journalists by an astonishing ratio of 17:1

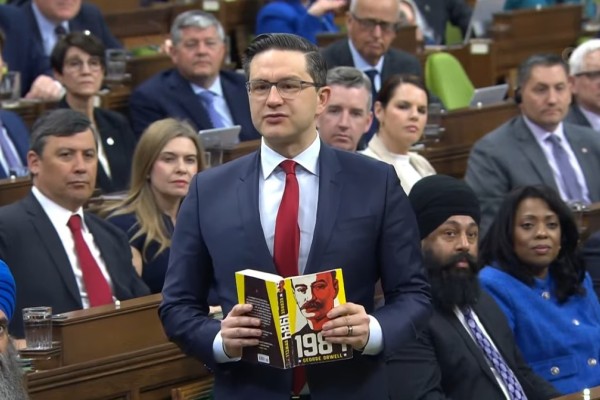

Research shows that more than 60 percent of Canadians believe journalists are purposely trying to mislead them, with government not far behind at 58 percent. Photo by Thomas Hawk/Flickr.

Special rapporteur David Johnston’s recent report into alleged Chinese election interference said basically “trust me, there’s nothing to see here,” which brought guffaws from coast to coast. Citing confidential intelligence sources which he could not divulge, Johnston assured Canadians there was nothing to worry about and no need for a public inquiry.

Skeptics instead pointed to his close ties to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and the Liberal Party. The extent of the whitewash was exemplified by former Conservative leader Erin O’Toole’s disclosure that Johnston met with party leaders to examine their evidence of interference only after his report had been written.

This attempt to sweep such a serious matter under the rug so obviously is further evidence of the federal government’s seeming belief that it can now easily control the media narrative. Most Canadians see right through the deception, however, as they are still well capable of putting two and two together. The older generation vividly remembers the outright lies told by the US government throughout the war in Vietnam, while almost everybody can recall the whoppers it told to justify its 2003 invasion of Iraq. More recently, Canadians have seemingly lost trust in government due to misinformation or even disinformation released during the recent pandemic. Even in invoking the Emergencies Act last year to deal with the truckers’ protest in Ottawa, the government similarly asked Canadians to simply trust that it was justified, which its own investigation subsequently confirmed.

It worked once, so why wouldn’t it work again? Well, one reason is that surveys have shown that public trust in both government and media has plummeted in recent years. A report by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford found last year that trust in news media here had dropped 13 percent since 2016, with only 42 percent of survey respondents saying they trusted “most news, most of the time.” Edelman, which publishes its Trust Barometer annually, found last year that 61 percent of Canadians believe journalists are purposely trying to mislead them, with government not far behind at 58 percent. An Abacus survey found that 44 percent of Canadians believe that much of the information they receive from news organizations is false. The government’s latest gambit won’t do much to allay suspicions.

Concern has grown in recent years over government and media being in cahoots since Ottawa began throwing hundreds of millions of dollars at news outlets five years ago. The $595 million media bailout runs out this year, however, so government and media are now working together to instead shake down Google and Facebook with Bill C-18, the Online News Act, which is currently under study in the Senate.

The level of disinformation has been breathtaking, with Ottawa claiming upon introducing the bill last year that more than 450 news outlets have closed since 2008 and that Google and Facebook are “stealing” newspaper content by merely carrying links to it. My research shows that the number is nowhere near that high, and that it has been systematically inflated to justify providing government financial support for media. The government estimate also conveniently omits the hundreds of online news outlets which have exploded onto the scene since 2008.

Our pliable news media have been taking government money to print disinformation disguised as news since well before the bailouts began, however. PEI Senator Percy Downe noticed in early 2017 as part of his work on overseas tax evasion that a number of “very positive articles” on the Canada Revenue Agency suddenly began appearing in major newspapers and on their websites. Downe well knew the CRA’s terrible track record of collecting taxes from Canadians hiding their money offshore, as not one person had been charged with overseas tax evasion in more than a decade, much less convicted, fined, or sentenced.

Articles began appearing in Postmedia newspapers, however, crediting the CRA with criminal convictions against 42 Canadians for evading taxes on $34 million of income between 2011 and 2016, with $12 million in court fines and 734 months of jail time resulting. Downe asked in the Senate how such disinformation could be spread by the CRA and he soon learned that it had paid Postmedia more than $288,000 to spread it. “So the next time you see an article in a newspaper or online talking about how good a job the Canada Revenue Agency is doing, check to see who paid for it,” he said in a press release. “It might have been you.”

The stories were not news but instead so-called native advertising, which is paid content disguised to look like news and has become an increasingly lucrative revenue stream for newspapers, even so-called “quality” titles such as the Toronto Star and the Globe and Mail. Former New York Times Executive Editor Jill Abramson called it “the industry’s new digital Frankenstein,” and her opposition to it reportedly cost her the newspaper’s top job.

Postmedia has been by far the worst offender in Canada, however, especially for its notorious pro-pipeline campaign begun a decade ago on behalf of the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers. A 2018 study by consumer groups found that any disclosure carried on National Post native advertising that it had been produced on behalf of a client was often “camouflaged.”

Then there has been the simultaneous diminution of journalists due to corporate cutbacks and the explosion of public relations operatives, which now sees journalists both overworked and vastly outnumbered. As Dwayne Winseck of Carleton University noted in his latest annual report on Canada’s media economy, while there were about 40,000 people working in PR, advertising and marketing in 1987, that number had quadrupled to about 180,000 by 2021, meaning that “the imbalance had ballooned to an astonishing 17:1.”

One effect has been a vast reduction in investigative reporting, as Dean Starkman noted in his 2014 book The Watchdog That Didn’t Bark, which has come as a result of several factors, including the nature of the Internet itself. The imbalance has resulted in what Starkman calls “the hamster wheel,” in which overworked reporters have no time to research investigative reports and increasingly rely on stories fed to them by PR operatives. At the same time, digitism has shortened attention spans and the Internet thus discourages long-form investigative reporting and instead tends more towards shorter, faster breaking news, access to which is often provided by co-operative PR types.

The so-called “digital first” model now followed by most news media outlets sees investigative reporting not as an asset, according to Starkman, but as a problem. It focuses instead on a quantity of coverage against which ads can be sold, creating what Starkman calls a “downward spiral of quality,” along with a downward pressure on ad rates. The result is clickbait, which can be calibrated by the use of precise audience metrics. The good news, notes Starkman, is that the paywall model newspapers have been increasingly adopting online as ad rates fall creates a “far more intimate relationship with readers.”

The shifting sands of the ongoing communication revolution are still settling, but it is abundantly clear so far that digital communication gives government an advantage over journalists. Canadians are right to be increasingly skeptical of its media messages and should under no circumstances simply trust what the government tells them.

Marc Edge is a journalism researcher and author who lives in Ladysmith, BC. His books and articles can be found online at www.marcedge.com.