Trudeau’s promises unravel in legal battle over Indigenous rights

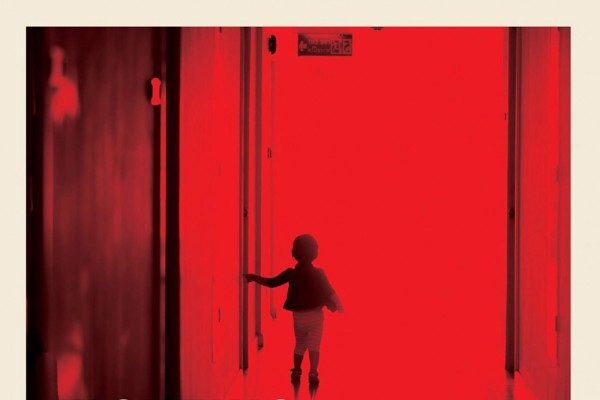

Photographer Aimo Paniloo captures Clyde River people of all ages making the Inuit facial expression for “no” to convey their continuing opposition to seismic surveys. The gesture — a squinting of the eyes and scrunching of the face — is the equivalent of shaking one’s head in the dominant Canadian culture.

Justin Trudeau’s Liberal Party campaigned on the promise of a “renewed, nation-to-nation relationship” between the government and Indigenous communities. Trudeau promised the Assembly of First Nations that he would govern “not only in accordance with constitutional obligations, but also with those enshrined in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.”

In a virtual town hall for the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network, he proclaimed that Indigenous peoples should have a “veto” over pipeline development, and that no “absolutely” means no. In Nunavut, Liberal candidate Hunter Tootoo repeated the promise that the Liberal Party would respect the right of Indigenous peoples to provide or withhold their consent for energy projects. Regarding oil and gas development in the Arctic, he told the northern media that, under the Liberals, it would be “the government that grants the licences, but the communities that grant permission.”

Less than a year after coming to office, the Liberals have scaled back this bold rhetoric. In May, Indigenous Affairs Minister Carolyn Bennett addressed the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. Bennett announced that Canada is now a “full supporter of the Declaration without qualification.” Bennett then proceeded to immediately qualify her apparently unqualified statement, by claiming that Canada’s existing constitutional obligations “serve to fulfil all of the principles of the declaration, including ‘free, prior and informed consent.’ ”

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami president Natan Obed wrote of his serious disappointment with Bennett’s speech, and claimed that it was “no clear departure from the Conservative government’s position” on Indigenous rights: “The rights affirmed by the UN Declaration must complement and build upon existing domestic laws and policies, not simply be re-interpreted in ways that align with them.”

Obed was right to be critical of the Liberal government’s approach to Indigenous rights. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) differs quite significantly from the Canadian constitution’s conception of Aboriginal rights. Both are complex legal instruments, with their own unique limitations and benefits. As far as government consultation with Indigenous communities is concerned, UNDRIP sets a much higher standard than the Canadian constitution. The Inuit community of Clyde River’s legal battle over seismic surveys shows that the National Energy Board, the Federal Court of Appeal, and the Attorney General of Canada continue to interpret the duty to consult in a manner which pales in comparison to the rights explicated in UNDRIP.

Nunavut Inuit oppose seismic surveys

In 2011, a consortium of geophysical companies submitted a proposal to conduct seismic surveys off the coast of Qikiqtaaluk (Baffin Island). Seismic reflection surveys are a method of oil/gas exploration, and have the potential to seriously disturb the marine mammals and fish Qikiqtaaluk Inuit rely upon.

The proposal was reviewed by the National Energy Board (NEB) and approved in 2014, against the wishes of Nunavut Inuit. At public meetings and in letters and petitions to the NEB, Inuit clearly and articulately voiced their opposition to the proposed surveys. Clyde River’s municipal council and Hunters and Trappers Organization passed a series of joint resolutions opposing the proposal. Later, a meeting of mayors from all Qikiqtaaluk communities passed a similar resolution. Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated and the Qikiqtani Inuit Association—the organizations which represent the Inuit of Nunavut and Qikiqtaaluk, respectively—insisted that the surveys not be approved until further baseline studies were conducted. This position was supported by the Nunavut Marine Council, consisting of representatives from all of the co-management boards created by the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement. Through these and other means, Qikiqtaaluk Inuit made it clear that they were withholding their consent for the proposed surveys.

After the surveys were approved, Qikiqtaaluk Inuit continued to voice their dissent. Residents of Clyde River held a series of protests, expressing their outrage with the federal government’s approach to consultations. The community then formed an alliance with civil society organizations and academics—including Greenpeace Canada, Idle No More, Amnesty International, the Council of Canadians and the Mining Injustice Solidarity Network—which together call themselves the Clyde River Solidarity Network. With former mayor Jerry Natanine serving as community spokesperson, the community’s opposition to seismic surveys was communicated to Canadians through the national media.

The community of Clyde River eventually turned to the courts, requesting the Federal Court of Appeal quash the permits issued by the NEB. The community submitted that they were not meaningfully consulted before the surveys were approved.

Photo from Pangaea-Project.org

The “duty to consult” in UNDRIP and the Canadian constitution

UNDRIP’s standard for consultations, and the related concept of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC), are contained in article 19:

States shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the Indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free, prior and informed consent before adopting and implementing legislative or administrative measures that may affect them.

In other words, if the government wishes to carry

out an action (e.g. pass a law or issue permits to an

oil company) that may impact an Indigenous community’s

rights, they must first obtain the consent of

the community. The Indigenous community is free to

provide or withhold consent.

It is important to note that this right is not an absolute veto over government actions—a common charge made by the agreement’s right-wing detractors. UNDRIP is explicit that the rights it contains must be balanced with the rights of non-Indigenous people. It clearly anticipates that its rights will be limited, but only in cases where limitations are “strictly necessary solely for the purpose of securing due recognition and respect for the rights and freedoms of others and for meeting the just and most compelling requirements of a democratic society.” Put another way, the rights contained in UNDRIP are relative to the human rights of others. If a government action is necessary to ensure the human rights of other people, then Indigenous peoples would not have the right to halt it.

The NEB’s review of seismic surveys fell dismally below the FPIC standard. There is no reasonable rationale for overriding the need for consent. No one else’s human rights would have been infringed upon if approval had been delayed, allowing further studies to be conducted. No one would have gone without food or shelter, been forced to suffer indignity or denied basic political freedoms. The seismic companies may have lost some money, but corporate profits are hardly a question of human rights.

The constitutional “duty to consult” that flows from the Canadian constitution is a relatively weak safeguard for Indigenous rights. This duty was developed in a series of Supreme Court of Canada decisions. Simply put, the duty requires the government to consult with Indigenous people before carrying out actions which may infringe upon their constitutionally protected Aboriginal and treaty rights. The degree of consultation required depends on circumstances, and exists on a “spectrum.” In cases where the Aboriginal right has not been well established, and where the government action is unlikely to cause significant interference, only minimal consultation is required. On the other hand, where the right is firmly established, and the government action has the potential to seriously infringe upon it, “deep consultation” is required. While the Supreme Court has not provided an extensive definition of “deep consultation,” it has made clear that it entails meaningful and transparent discussion, analysis and accommodation of the issues of concern to the Indigenous community. Further, the court has found that the “full consent of the Aboriginal nation” may be required in consultations, but only “on very serious issues.”

The NEB’s review of seismic surveys also fell well below the standard provided by the Supreme Court. Because the Inuit right to hunt marine mammals is enshrined in a modern treaty—the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement—deep consultation was required. At the public meetings held by the NEB, neither the seismic companies nor the NEB could answer the most basic questions from Inuit about the potential impacts of the surveys on marine mammal hunting. Further, the government refused an extremely reasonable request for accommodation: that a broader regional assessment be conducted to collect further baseline data.

Federal Court of Appeal sides with Ottawa

Challenge goes to Supreme Court

Clyde River submitted an application to appeal the case to Canada’s Supreme Court in October 2015. In their application, they argued that the federal court’s definition of “deep consultation” rendered the duty to consult “meaningless.”

On November 23, roughly one month after Trudeau came to power with a promise to implement UNDRIP, the Attorney General of Canada submitted a response to Clyde River’s application. The submission argued that the appeal should not be granted, in part because the federal court’s decision did not “contain errors of law or venture into areas of uncertainty in the law.” The federal government, in other words, agrees with the federal court’s limited definition of consultation, which leaves no room for FPIC, even in the most serious cases. Despite the bold rhetoric from the Liberal Party, the state’s lawyers have continued to promote an interpretation of Aboriginal rights which is considerably more restrictive than that contained in UNDRIP and Supreme Court rulings.

The Supreme Court agreed in March 2016 to hear Clyde River’s appeal. Since that time, myriad groups and individuals have applied to intervene in the case. The list of potential interveners includes Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated, the organization which represents all Inuit in Nunavut, along with the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board, a co-management board created under the Nunavut Land Claim Agreement. The organizations representing Inuit in the Northwest Territories and Arctic Quebec—the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation and the Makivik Corporation, respectively—have also applied to intervene. Also included is a joint application by four Inuit politicians who have played substantial roles in the fight for Inuit constitutional rights since the 1970s: Senator Charlie Watt, former MP Peter Ittinuar, former ITK president Rosemary Kuptana, and former ITK president Tagak Curley submitted a joint application to the court. The court has also received applications from several First Nations communities in Alberta and British Columbia, as well as the human rights lobby group Amnesty International. The Canadian Chamber of Commerce and the Attorney General of Saskatchewan have also filed to intervene, along with the National Energy Board.

At the time of this writing, the Court had yet to release its decision on intervener applications. However, the fact so many parties have applied makes one thing entirely clear—the outcome of this appeal will have significant consequences for the rights of Indigenous peoples in Canada. For better or for worse, the Supreme Court’s decision will set a powerful legal precedent, and will likely have a substantial influence on the way UNDRIP is implemented in Canada. What’s more, the submissions from the Attorney General of Canada will be a test of how serious the Liberal government is about creating a “new relationship” with Indigenous peoples. Will they direct the attorney general to adopt a new approach, or will they sit silently and watch while their lawyers argue for a watered-down version of the status quo?

Regardless of what transpires, this case should be of great interest to the Canadian Left. Given Canada’s colonial history and present, the rights of Indigenous peoples should be of the utmost importance for all Canadians. It is a simple question of social justice. The notion of FPIC, however, has a special affinity to the struggle for socialism. If we define the socialist movement as a movement to extend democracy into the sphere of “the economy”—and I, for one, think we should—then it follows that the movement to implement FPIC is in and of itself a part of the struggle for socialism. The fight for the right of Indigenous peoples to democratically determine the conditions under which the industrial system (capitalist or otherwise) penetrates their lands and lives is one of the most pressing struggles to democratize the economy unfolding in Canada today.

An earlier version of this story incorrectly referred to the “auditor general” of Canada rather than “attorney general.” We apologize for the error.

This article appeared in the Autumn 2016 issue of Canadian Dimension (Leap, the Left & the NDP).