‘Too little, too late’: Don’t wait for CSIS to stop the rise of right-wing extremism in Canada

While some observers hailed the federal government’s recent addition of the Neo-Nazi groups Blood & Honour (B&H) and Combat 18 (C18) to the national terrorist list as symbolically important, analysts point out that Canada’s security services are doing far too little, far too late to address the broader dangers of the far-right. Instead of counting on law enforcement, social institutions and organizers must coordinate a comprehensive response to the rise of right-wing extremism.

Last month, the federal government announced that B&H and C18 would be the first far-right groups featured on Canada’s list of banned terrorist organizations. Under this new designation, the two Neo-Nazi organizations are liable to have their assets frozen and their members subject to Criminal Code sanctions.

However, this incredibly late response comes after the groups committed violent actions for nearly two decades.

B&H emerged out of the British Neo-Nazi music scene during the late 1980s, while its “armed wing”, C18, was originally set up as a security detail tasked with protecting leaders of the Neo-Fascist British National Party in the early 1990s. Both groups gradually expanded into an informal network of international chapters, carrying out murders and bombings along the way.

By the 2000s, B&H had found its way into Canada, with the bulk of the group’s activities concentrated in Calgary, and later Edmonton.

During B&H’s most active years in Alberta (the group originally operated under the name ‘Aryan Guard’), members were convicted for violent attacks against racialized peoples and left-wing activists. In 2010, for example, four masked men carried out a home invasion of Alberta Communist Party member and anti-racist activist Jason Devine, leading to the arrest of B&H’s then de facto leader, Kyle McKee.

But the far-right group wasn’t just in the business of one-off assaults. In 2012, McKee, who provided assistance for other Neo-Nazis looking to move to Alberta from out of province, was caught in possession of assault weapons and ammunition in his Calgary apartment. That finding was hardly a surprise to local police, though, since McKee frequently uploaded photos of himself posing with the weapons in front of Nazi flags.

Meanwhile, during the years that McKee was busy stockpiling weapons and coordinating B&H’s violent expansion, the Canadian Security Intelligence Services (CSIS) chose to invest time and resources gathering intelligence on peaceful environmental and indigenous groups.

According to declassified documents released by the BC Civil Liberties Association on July 8, CSIS kept files on non-violent activists who protested the failed Enbridge Northern Gateway pipeline project, and shared such information with the petroleum industry and the National Energy Board.

While CSIS did finally acknowledge the growing threat posed by right-wing groups in its most recent public report, the security agency’s fixation on peaceful left-leaning groups and longstanding inaction on right-wing violence is one of the reasons Barbara Perry, a social sciences professor studying hate crime and right-wing extremism, is unimpressed by the government’s listing of B&H and C18 as terrorist entities.

“It is far too late,” she said. “Law enforcement and intelligence have not just failed to acknowledge the threat of the extreme right in the past; they have explicitly denied the threat, allowing groups to act and in fact proliferate under the radar.”

“The move is not likely to have a broad impact,” she added. “Law enforcement and intelligence generally have been obsessed with Islamist inspired extremism and left-wing extremism.”

More alarmingly, Perry pointed out, many members of extreme right-wing groups are finding new homes in mainstream organizations, such as the Yellow Vest and the United We Roll movements. With the boundaries increasingly blurred between traditional conservatism and hardcore Neo-Nazi groups, rooting out violent extremism becomes a near impossible task for the security services.

“[Right-wing extremist] sentiments are not that far removed from mainstream ideologies, both political and popular,” she explained. “Witness the many public opinion polls in the past couple months that reflect a hardening of conservative and reactionary sentiments around immigration, Islam, multiculturalism.”

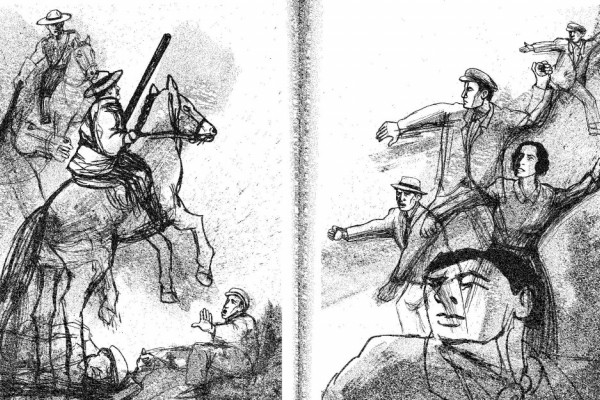

Blood & Honour was described by the government as “an international neo-Nazi network whose ideology is derived from the National Socialist doctrine of Nazi Germany.” Photo courtesy of Anti-Racist Canada

A poll last month indicated that 63 percent of Canadians think government should prioritize limiting immigration. Meanwhile, reports of prominent conservative politicians keeping company with right-wing extremists have become an all too familiar sight: in February, federal Conservative leader Andrew Scheer shared a stage with white supremacist Faith Goldy at a United We Roll rally; last October, three members of Alberta premier Jason Kenney’s United Conservative Party were pictured with members of Soldiers of Odin; last month, People’s Party of Canada leader Maxime Bernier struck a pose with members of the violent anti-immigrant group Northern Guard at Calgary Stampede.

And while those leading conservative figures rub shoulders with members of hate groups, racially motivated violence continues to rise. Hate crimes against Muslims in Canada increased 253 percent between 2012 and 2015, while similar crimes against Jewish people increased 16.5 percent between 2017 and 2018, according to Statistics Canada. Alexandre Bissonnette, who gunned down six men at a Quebec City mosque in 2017, obsessively consumed content from several mainstream right-wing media personalities, including Tucker Carlson, Laura Ingraham and Ben Shapiro.

So, at best, marking out groups like B&H as terrorist organizations means a very small number of far-right activists can no longer operate under the same names and leaders as they once did. But the truth is that, as Candyce Kelshall, an affiliate at the Canadian Network for Research on Terrorism, Security and Society notes, the fluid organizational structure of violent right-wing groups makes rebranding and avoiding detection relatively easy.

“While these measures can serve as a deterrent, our research suggests that taking these steps could potentially drive these groups underground or into a name change where it becomes more difficult to track them,” she explained. “We might think of these entities more as a movement and less as a group.”

According to Perry, the inability or unwillingness of law enforcement to properly deal with right-wing extremism is why a deeper social response to reactionary politics is what’s required.

“This is much more than a law enforcement issue,” Perry explained. “Confronting the extreme right demands a multi-sectoral response that includes education, civil society, public health, social services, even mental health services.”

“We need to have a public dialogue that does not simply uncover these groups, but that also deconstructs the mis/disinformation that informs their strategies.”

In short, don’t wait for CSIS and the police to stop the far-right: that’s a task only mass social organization and solidarity are capable of accomplishing.

Alex Cosh is a PhD student and journalist based in Powell River, BC.