The fix: Inside Laurentian University’s demise

The institution was restructured to align the curriculum with market demands—an administrative task, not an intellectual one

In April 2021, Laurentian University announced plans to cut 58 undergraduate and 11 graduate programs and lay off more than 120 faculty. As Ron Srigley writes, this move signaled the craven capitulation of the institution to market demands. Photo from Twitter.

What happened to Laurentian University? How did a publicly funded Ontario university go to the edge of bankruptcy without anyone intervening before the crisis became inescapable? And if it was a crisis, why didn’t the provincial government intervene, as it has with countless other public institutions and private corporations? What are we to think of a “restructuring” that eliminates the disciplines that define the institution it claims to be saving? Is a university without economics, mathematics, politics, philosophy and physics still a university? And why is the administration now trying to prevent the Ontario Auditor General from reviewing all pertinent materials necessary to complete her value-for-money audit? Why the secrecy?

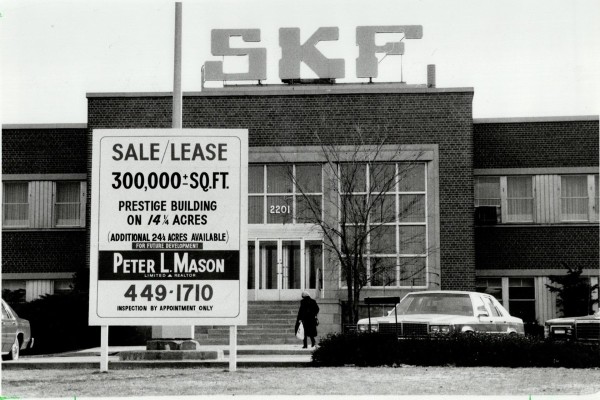

Laurentian president Robert Haché and the university’s board of governors have for their part placed a big, bright sign on Laurentian’s digital front lawn saying, “Nothing to see here, folks.” And soon we won’t. Down the memory hole Laurentian will go, along with all the other dreadful things we’ve witnessed this past year. Just another casualty of hard economic times, rescued by tough but necessary administrative intervention that respects privacy and confidentiality.

Before it disappears, we should pause to reflect on what happened to Laurentian. Haché and his administration manhandled the university in a way we’ve not seen before in Canada. Administrative brutality is nothing new. But it was jarring, nonetheless, to see an institution Canadians once regarded as almost sacred treated like a low-rent commercial interest. All my people were working class. None had ever attended a university. But they all revered them, because they knew from their own experience that understanding things deeply and comprehensively was important. No class hatred, no resentment. Just respect for a place where serious matters were examined by serious people.

Laurentian is no longer this type of institution. It has been restructured to answer to market demands, according to which profitability determines field of study and scope of inquiry rather than independent judgments of worth. As Haché says, the new Laurentian differs from the old in that it teaches “what students want to learn.” Traditionally, Canadian universities respected their students too much to teach them only what they wanted to learn. They also taught them things they needed to know. Universities required arts students to take science courses and science students to take arts courses because they believed that things other than preference, to say nothing of market demand, were essential to a student’s cultivation. The aim of such an education was to cultivate people who were free, magnanimous, and capable of mature judgment about the world, including their own society. You may decide for yourself whether our world would be a better, less menacing place had our scientists, artists, and writers continued to study such things together.

The university that I’ve just described no longer exists. It’s been replaced by institutions like Laurentian, which are now being forced by administration and government to answer ever more completely to economic imperatives. The deed is done. Soon the waters will cover over everything, the whole affair will be forgotten, and we’ll barely remember there was even a disturbance. But before that happens, we can at least anchor a few buoys to mark the place and perhaps provide a warning for those who might find themselves sailing this way again.

The official version

On January 30, 2021, Laurentian University president Robert Haché submitted an affidavit to the Ontario Superior Court of Justice declaring the university insolvent and making an application to begin proceedings under the Companies’ Creditors Arrangement Act (CCAA). The submission was framed as a final, valiant attempt by the administration to save the institution from bankruptcy.

Here is Haché’s version of events. Laurentian University had experienced years of annual deficits in the millions of dollars, going back as far as 2014–15. Those deficits were caused by changes beyond the control of the administration, principally declining enrolment and rising operational costs. The administration successfully managed these changes through a combination of tuition-fee increases, aggressive student recruitment, and campus modernization. But several factors—among them a 10 percent tuition reduction mandated by the province in 2019, continuing decreases in enrolment, rising faculty costs, and loss of revenue from international students and ancillary fees due to the COVID-19 pandemic—compromised the administration’s efforts, rendering Laurentian’s financial situation untenable.

In a last-ditch attempt to save the university, the administration informed the Laurentian University Faculty Association (LUFA) that there was a “material risk” that the university could become insolvent as early as the fall of 2020. It requested rollbacks in compensation to stave off the crisis. According to Haché, LUFA responded by stalling, preventing timely intervention through repeated requests for more financial documents. By October 2020, collective bargaining had been suspended pending a review of the university’s finances. When the two parties resumed negotiations in January 2021, Laurentian advised LUFA that its financial position had deteriorated further. LUFA repeated its claim that the documents provided did not demonstrate an immediate financial crisis and notified the university that it intended to bring an unfair labour practice complaint against it.

On February 1, Haché notified the Laurentian community of the university’s insolvency. On February 12, Laurentian was granted creditor protection and began restructuring under the CCAA.

According to Haché’s affidavit, the only group not responsible for Laurentian’s financial crisis was the group responsible for Laurentian’s finances: Haché and the university’s board of governors. Though administrations may often fall prey to events and actions beyond their control, it is their job to manage them. They are responsible, even for things they cannot control. Indeed, there are clear provisions in the university’s collective agreement (CA) for what must be done in the event of a financial crisis. Haché and the board never invoked them, even though they knew, for well over a year and quite possibly longer, that Laurentian’s financial situation was untenable.

Why not? Why allow the university to go bankrupt? Were the administrators incompetent? Reckless? Or did the prospect of insolvency have an appeal of its own?

Closing the open-door system

In his submission to the court, Haché asked the crown to seal two letters, one from the Ministry of Colleges and Universities dated January 21, 2021, and another to the Ministry dated January 25. “The correspondence contains sensitive information,” he argued, “that, if disclosed publicly, could jeopardize the ability of the Applicant to complete a restructuring.” In other words, something was said in these letters that was so compromising that it posed an existential threat to the university. The judge, Superior Court Chief Justice Geoffrey Morawetz, granted the request, together with Haché’s further petition that all requests to the university under the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA) be suspended during the stay of proceedings as Laurentian lacked the staff to process them. In combination, the insolvency declaration and the CCAA procedures meant that any analysis of Laurentian’s finances and any decision regarding its restructuring would occur in private, beyond public scrutiny.

Haché’s argument amounts to a claim that senior management was either too busy, or the information it possessed too compromising, for such material to be released to Ontarians. Here is what Ontario’s Information and Privacy Commissioner (IPC) had to say about the first claim: “As far as the IPC is aware, there has never been an order to suspend FIPPA obligations made in the course of a CCAA proceeding.” Never. Every corporation that’s sought protection under the CCAA has been compelled to comply with the Act. But not Laurentian—a public institution. An assertion of mere busyness was enough to persuade Judge Morawetz to waive the Act’s provisions in precisely the type of circumstances for which they were created. He even denied the IPC’s comeback proposal, that the court grant an order “less broad” in scope that would accommodate the university’s supposed staffing problems while preserving the integrity of FIPPA.

As to Haché’s “too compromising” argument, it sounds like the usual blackmail. Keep your eye on the pronouns: We did/said something dreadful and, if it comes out, you will pay the price. Given that we always pay, why not call their bluff? How it clears the air to hear the truth spoken in public. We might have a real debate about the state of our universities with real choices in the offing, instead of a tedious, infantilizing melodrama in which wise administrators relieve the weary many of the burden of knowledge, in the assumption that they are too stupid to understand it.

In fact, Laurentian’s board of governors and senior administration received millions of dollars in public funds to operate the university, and now the public would like to know what they did with them. That’s what accountability means: an accounting of where the money went, by the people who spent it. The arrangement reached between Haché and the court guarantees that this will never happen. Final decisions will be made behind closed doors, away from public scrutiny; and they will be made by a single body within the university: the administration—the party responsible for the crisis.

In other words, at the very moment when a public reckoning is straightforward, legally mandated, and essential, suddenly it is also impossible. Up is down.

Market-friendly restructuring

Former Ontario Minister of Colleges and Universities Ross Romano and his advisor, Alan Harrison, have deflected criticism from Haché’s administration and the Ford government by arguing that Laurentian’s financial problems were not new but “many years” in the making. They were neither caused nor even exacerbated by the pandemic. A former Laurentian president, Dominic Giroux, together with past governors Floyd Laughren, Michael Atkin, and Jennifer Witty, have responded to Romano and Harrison’s charges by arguing that the crisis was not their doing either, but the result of a “perfect storm” of events that no one could have anticipated and which, together, pushed an otherwise financially sound institution to the edge of bankruptcy. There was the misadventure at the Barrie campus, of course, but that was due to the government’s unwillingness to support the initiative. Apart from that, it was all just cruel fate. The only real culprit that both sides agree on is the professors. If only there were fewer of them and they made less money, everything could have been managed.

It comes as small surprise that these rival administrative camps were successful in getting at least one of their wishes. There will be no open review of the finances to determine whether their stories make sense. No explanation of how the missing $36.5 million in misappropriated research funds and donations were spent, and by whom. That’s all just spilt milk now, about which any opinion regarding culpability is possible since the actual details will never be known. But at least the professor problem was solved. At last count, about 137 faculty members were fired or retired—a 39 percent reduction. Administrators and staff were terminated too—about 16 percent of them, in aggregate. To an independent observer, those proportions may seem odd. Shouldn’t the reductions have been roughly equivalent given that fewer and smaller programs meant less work to support? It is a reasonable assumption, but not one that applies to the modern administrative university. Some 61 percent of Laurentian’s full-time employees are now staff and administrators; just 39 percent are professors. For every person doing the work of the university, there are 1.6 people doing something else.

To think that these people are supporting faculty is a delusion. Rather, they are replacing them as the real centre of power within the institution. This is what restructuring means: more administrators and fewer faculty, and ever more precariously employed, don’t forget, so that Laurentian can get on with its real business: aligning the curriculum with market demands, an administrative task, not an intellectual one.

The quarrel between Giroux’s liberals and Romano’s conservatives is a sideshow, the effective truth of which is to obfuscate an administrative agenda shared by both sides. That’s why their mutual recriminations are enough to raise doubts about culpability but not enough to support serious analysis of either side. Who would want that? If someone were to start pulling on that thread, who knows where it might lead? Giroux and his friends did not object to purging the faculty and bolstering the administration. They express no reservation at all about the use of the CCAA. And they do not demand a financial audit, the simplest and most obvious way to prove their case. Instead they obligingly echo Haché’s empty rhetoric about a stronger Laurentian emerging from the ruins and even give the ministry a walk, exhorting it to “recognize and support this extraordinary asset for life in Greater Sudbury.”

So much for truth—even basic historical truth—in the modern administrative university. Even the opposition is in on it. With each new critical commentary, the tide covers over a little more of the wreckage.

Laurentian was driven to the point of financial ruin and misspent millions of dollars, yet not a single administrator, going back over a decade, was in any way responsible for it. Accountability? What accountability? It behooves us, I think, to tug on a thread or two of the administration’s narrative, to glean at least a remnant of truth about what happened to Laurentian. It may not get us to the bottom of things, but mapping the sequence of events will help us better understand how the insolvency came about, who caused it, who stood to profit from it, and how. It will also afford us some insight into the people running our universities and a sense of what their actions mean beyond the relentless PR about stronger, better, brighter futures and jobs jobs jobs for all.

Laurentian University President Dr. Robert Haché. Photo by John Lappa/Sudbury Star.

Sandbagging and skullduggery

Mr. Haché assumed the presidency of Laurentian in July 2019. He was an outsider to the institution and a first-time president. Whether or to what extent he understood the crisis prior to his appointment is impossible to know (although a look at the parachute clauses in his contract might shed light on that). What we do know is that by November 2019, only a few months after taking control, he was discussing Laurentian’s “financial challenges” openly with Mr. Romano’s ministry and continued to do so throughout 2020, right up to the declaration of insolvency on February 1, 2021. More important still, we know that on April 27, 2020, his negotiating team advised LUFA that the university could become financially insolvent “as early as the fall of 2020.” By November the prediction had come true. On November 12, at a special session of the board of governors, an ad hoc committee was struck to address the crisis and to begin preparing documents for CCAA hearings.

Given their understanding of the scope of the crisis, why didn’t Haché and the board follow the university’s collective agreement and declare a state of financial exigency in late 2019 or early 2020? According to the CA, such a state exists when “substantial and recurring deficits… threaten the long-term solvency of the University as a whole.” Clearly this was Laurentian’s position; yet, for well over a year, neither Haché nor the board of governors took action. Why not?

As noted above, Haché attempted to blame LUFA, claiming that it had failed to review financial documents expeditiously and in good faith, thus precipitating the insolvency. Like so much in the administration’s narrative, this account does not make sense. LUFA clearly knew something was wrong. But its documented responses strongly suggest that the financial data necessary to understand the full extent of the crisis were repeatedly withheld from it. Even some who support Haché’s views about obstructive faculty and inefficient programs have argued that the administration’s numbers don’t add up. Why would faculty have viewed them any differently? And why shouldn’t they have insisted on a full explanation during contract negotiations, given that it is their legal responsibility to do so?

Once you get past the sophistry, a different story begins to emerge. Perhaps Haché and the board did not declare financial exigency because they did not want to. Perhaps instead they sandbagged LUFA for almost ten months, threatening it with the university’s imminent collapse and then baiting it by coyly refusing to produce the evidence. And as they played out the string, Laurentian inched steadily closer toward complete financial ruin and the CCAA.

It’s difficult to believe that Haché would have allowed such a thing to happen without some kind of assurance. He was a new president with little social capital within the institution. What if there were no rescue? What if the CCAA request were denied? Consider his exposure, given that he and the university governors had flouted provisions for financial exigency that could have saved the university and exonerated him. Why would he have risked such a thing? He could have allowed events to happen and then simply played dumb. His suggestion, at a meeting of the university’s senate in the winter of 2021, that he was unaware of the crisis until December 2020, was such a strategy—although a bizarre one given the overwhelming evidence to the contrary, including his own written testimony. Still, there would have been no back door for Haché, as there was for past presidents Giroux and Zundel, as the university’s failure was imminent.

Alan Harrison, appointed to advise Romano about Laurentian’s situation, absolved Haché of responsibility for the crisis only two weeks after insolvency was declared. It was a strange announcement, one which became stranger still the more you thought about it. If the crisis was full blown by the time Haché assumed the presidency, then why did he not act immediately? Why wait nineteen months? And given that he did wait nineteen months, clearly the crisis deepened under his administration and so he did bear responsibility for it. Either way, Haché was implicated.

Harrison’s exoneration of Haché becomes even more problematic when we consider that the two men had worked together in the past. Haché was a senior administrator at the University of Calgary during Harrison’s tenure there as provost and vice president academic. Why would Romano commission a report about a university insolvency potentially involving administrative malfeasance on the part of a man who had worked closely with the key figure in the investigation? In what universe does that qualify as transparent and responsible oversight?

That was not the only problem with Romano’s handling of the matter. There is his own role to consider too. For one thing, Romano made conflicting statements about when he learned of Laurentian’s situation. Was it January 2021? Or six months earlier? Or was it perhaps at the beginning of the pandemic, in March 2020? In response to my request for clarification, his office settled on January 2021 as the date.

Given Haché’s explicit statements to LUFA in early 2020 about impending insolvency, given his repeated, documented conversations with the ministry about Laurentian’s financial challenges from 2019 through to 2021, and given that the government has five appointees on the university’s board of governors, it is simply not possible to believe that Mr. Romano was unaware of the situation prior to January of this year.

So, as with Mr. Haché and the board, why didn’t Romano act? Why knowingly allow a public Ontario university to become insolvent? What could possibly be gained by such reckless behaviour?

Administration power play

The official narrative is that the insolvency was a misfortune that was valiantly resisted by the administration but ultimately proved insuperable. I do not believe that is what happened. I think at some point during Haché’s administration¬—sometime between mid-2019 and early 2020—an idea began to take shape within the university’s senior administration, board of governors, and perhaps even Ontario’s Ministry of Colleges and Universities that the best way to handle Laurentian’s fiscal crisis was not to solve it but to push the institution inexorably toward insolvency and the CCAA. Mr. Romano was well acquainted with the nature and benefits of the CCAA, having been actively involved in supporting Algoma Steel as it went through the process in 2017 and 2018. Even the court-appointed monitor for Laurentian’s insolvency was the same one as had been appointed for Algoma Steel’s.

Be that as it may. A manufactured crisis is not a crisis; it’s a plan. So, what might the plan have been?

The first thing that the CCAA guaranteed was blanket immunity for everyone responsible for the debacle—the board for its complicity and failure of oversight, the government for its negligence and perhaps its cooperation, previous administrations for causing the crisis, and Haché for allowing it to deepen irreparably. Everyone who had a hand in creating or exacerbating the insolvency would walk, because the CCAA hearings are sealed and concerned solely with resolution of the fiscal problem. But those are only the hush money and crisis management parts of the equation. The real ambition lies elsewhere.

The CCAA granted Haché and the board of governors virtually unlimited power to reshape the university as they wished. The provincial government seems to have permitted, and perhaps even encouraged this effort by allowing the insolvency to proceed rather than advising the administration to follow the mandated provisions for financial exigency. In other words, the executive branch of the university, with the knowledge of the provincial government, conspired to silence the university’s legally constituted legislative branch—the Senate—in order to restructure Laurentian without restraint and without any academic oversight of any kind.

In mid-April, Haché notified Laurentian publicly that the Senate had voted in favour of the restructuring plan, publicly implicating it in the deed. The Senate did in fact vote in favour of administration’s cuts, but whether it “supported” them is another matter entirely. Is a senate that’s forced to ratify an agreement that it did not make and could not amend, under threat of the dissolution of the university, still a senate? “Agree to eliminate seventy programs—including physics, mathematics, political science, history, midwifery, and engineering—and then fire a third of the faculty. Or else. You’ve got two hours.” At Stalin’s Moscow show trials, it wasn’t enough simply to kill the alleged perpetrators. They had to “confess” first, so no judgment of the executioners was possible. There is no killing today, fortunately, so there is always something to be thankful for—just mass firings and the threat of prison, should anyone get it into her head to start talking.

Trump’s response to the 2020 United States election is a contemporary example of the same practice. The country’s legislative bodies all agreed about the outcome of the election. But Trump insisted that he, and he alone, the leader of the executive branch, should decide the matter, even if it meant coercing states’ governments and the US Senate. In the event, Trump failed. America’s institutions are, thankfully, still sound enough to resist such an abuse of power. But not a legally constituted Ontario university. A compromised board of governors, a complicit senior administration, and perhaps even a ministry of the provincial government were able to turn Laurentian University’s governance on its head, and to do so in broad daylight and with the full cooperation of the courts.

Financial exigency would have allowed the university to chart a way out of the economic disaster created by the board and the administrations of Dominic Giroux, Pierre Zundel, and Robert Haché. It would even have permitted drastic measures, like program closures and faculty and staff terminations. But to do so, it would have first required a full public accounting of the university’s finances, a forensic audit of what actually happened. It would have required that all decisions be made by representatives of both branches of the university along with its labour unions. And the entire process would have required that any action taken be designed to preserve, first and foremost, the institution’s primary mission: to pursue the truth in its many fields of inquiry and to teach students to do the same. In other words, had it declared a situation of financial exigency as it was legally mandated to do, Laurentian would have gone through a process that was patient, prudent, robustly democratic, and completely transparent to the citizens of Ontario.

By secretly pursuing insolvency and protection under the CCAA, Haché and the board of governors did the opposite: they ensured that they alone would “restructure” the university, that no one would ever know what happened to the money, and that the first thing to go would be the university’s academic programs. No checks and balances, no consultation or discussion, and to hell with collective agreements and institutional governance. Just shut up and do as we say.

A road map for administrative control

The first overt attempt at an administrative takeover of an Ontario university occurred during the 1990s at McMaster University, where I was a graduate student at the time. The initiative was led by a committee called PAGIC—the Provost’s Advisory Group to Initiate Change. Interestingly, one of the group’s primary architects was the same Alan Harrison whom Mr. Romano chose to advise him about Laurentian’s insolvency and restructuring.

When PAGIC released its final report in October 1993, it set off a firestorm at McMaster. The resistance was swift, widespread and, in the short term, successful. Within a few months, the advisory group was dissolved and its report abandoned, most of the key players moving to other positions within and outside the university. But despite its opponents’ early victory, the administration won in the end. PAGIC was forgotten, but the administrative absorption of the university continued apace. McMaster, like Laurentian, is now just another administratively controlled public university, but one with deep-enough pockets, a strong-enough faculty association, and sufficient economic and reputational clout to withstand the province’s most ill-advised plans, at least for now.

The PAGIC report is a road map for administrative control. The Group’s first recommendation is the foundation for the entire document: “That the arbitrary distinction between financial and academic decisions, which has been seen to preclude the Senate from considering financial matters, be removed.” In fact, McMaster’s senate was not precluded from considering financial matters; it was protected from them so that it could make sound academic judgments that could then be debated and implemented as money permitted. And there is nothing “arbitrary” about the distinction. Academic decisions concern the scholarly merit of programs, faculty, and departments; financial decisions concern how much they cost. Keeping them separate is essential if you wish to avoid the administrative delusion that programs and people who make money are more valuable than those that do not.

With the distinction between financial and academic value eliminated, the PAGIC report’s authors turn to the question of who should make academic decisions. First, they remove the senate from the decision-making process entirely. They admit this may seem odd, given that a senate’s purpose is precisely to make academic decisions, but claim there’s good reason for it. Here’s the money quote: “It is our view that planning of this kind cannot be formulated effectively by a committee. Rather, it requires individual leadership. The development of an academic plan should be the responsibility of the Provost, in consultation with the President and deans.”

As envisioned by PAGIC, the university’s primary academic body would no longer make academic decisions. Only administrators are qualified to do that. And not all administrators, but just one—the provost. The senate will have a subcommittee—the Senate Resources and Accountability Committee (SRAC)—that will make both academic and financial decisions. But those decisions will not go to the senate for discussion, amendment, and approval, but “through the President to the board.” Why? Because the senate “might not wish to approve” them.

As for SRAC, it will have “the authority to recommend closure of programmes, units, or departments when contributions are not consistent with the costs.”

So, programs and faculty that make money will be kept, those that do not will be cut, because programs and faculty that make money are better.

What about cuts to the administration? According to the report, while administrative costs “can be easily identified, it has proven more difficult to find a common measure of workload. Without that, we have not been able to provide a comparable basis for making budgetary decisions for the two aspects of the university.” Unlike academic value, the value of the administration of resources cannot be determined by the cost of the administration of resources. In the absence of such a determination, it is impossible to know whether you have enough administration. Historically, this has meant that there is never enough administration.

And there you have it. Academic value is measured by profitability, as determined by administrators; administrative value cannot be measured financially and is determined by administrators. Academic decisions must be made by administrators, because academics might not approve them. And such a process is better than normal deliberative processes, because all decisions will be approved, because disapproval will not be permitted.

The attempted administrative takeover of McMaster in 1993 and the successful takeover of Laurentian in 2021 were both justified by financial crises said to require unprecedented intervention to be averted. No such crisis materialized at McMaster, which surprised no one who had examined the PAGIC report closely. The initiative was never about saving money but rather concentrating power in the hands of the administration. As for Laurentian, though its financial difficulties were real, no serious attempt was made to solve them. The institution was allowed to descend into insolvency and the CCAA as a means of achieving total administrative control. The crises, in both cases, were merely pretexts.

The difference was that PAGIC still had enough of the old university in it that it sought to persuade with speech, as guileless as it was. Haché and Laurentian’s board of governors made no argument, advanced no position. They dispensed with speech altogether, in favour of power. Laurentian is McMaster for the 2020s—stupider but more brutal, sleazier but more effective.

Laurentian’s administrators could do this because they already controlled the university. They were not yet able to fire people and close programs at will, but they could juke the stats, toy with LUFA, deceive the Senate, and mislead the entire university community, for years, about the institution’s true financial situation. That is in part why the resistance of the faculty was so ineffective compared to what occurred at McMaster. The administration had backed them into a corner from which there was no escape. If the Senate accepted the administration’s plan, it would betray the faculty and compromise its own moral and legislative authority. If it rejected the plan, the administration would allow the university to go into receivership and Laurentian would cease to exist. In other words, refuse to sign and the university is finished, or sign and it belongs to us.

We know how the Senate chose, in the end. My point is neither to judge nor exonerate them (what would you or I have done in their place?) but to make plain the brutality of Mr. Haché, the board of governors, and those who aided them.

A rally organized by student midwives was held in Sudbury on April 16, 2021 to protest Laurentian University’s program closures. Photo by Lou Hayden/Our Times.

Universities pimped to the market

The Laurentian insolvency was an authoritarian abuse of the institution led by Mr. Haché and the board of governors, and was carried out with the knowledge, and perhaps even the approval, of the provincial government. That alone is enough to declare them unfit for office and to seek their removal. No matter what you think about universities—what they are or what they should be—this sort of administrative thuggishness dirties us all and compromises the institution fundamentally. It’s not mere dereliction of duty we’re talking about, but an intentional violation of a legally constituted public institution to advance an agenda at odds with its stated purpose.

As to that agenda, we must be frank: who are Mr. Haché and the board of governors to decide that a Canadian university should no longer teach, among other things, politics, philosophy, history, mathematics, religion, theatre, music, indigenous traditions and languages, and physics, disciplines that cross every racial and national boundary, that embody our collective pursuit of wisdom, and whose provenance is measured in millennia? Are we going to allow this ship to sink because a few hired money people in Sudbury have judged it to be unprofitable? It’s almost a parlour game today to denigrate professors—expensive, irrelevant, obstructionist, boring. But who do you want to teach your kids? These people, who have laboured in obscurity, often for decades and to the point of penury, simply to understand, honestly and clearly, some feature of our human condition, or the market and its shills? We bow before power today and celebrate its many achievements. But power is a soil out of which monsters also grow. It may be that we will not fully understand what we’ve done until the monster turns to face us.

We must begin with what our children need to know, which is a qualitative judgment made by mature people with broad concern for the good of their society and its citizens. Then we can think about how to pay for it. To kowtow to market forces is an egregious abandonment of adult responsibility for the education of the young. The constant ballyhoo about money is merely cover for administrators’ irresponsibility in this regard and the provincial government’s stated intention to pimp the university’s curriculum and students out to the market. No serious person thinks that the material realities of employment are unimportant or can be ignored. No arts or science professor that I know of believes or would say such a thing. What professors are furious about, rather, is the erosion of the quality of university education that has resulted from the foolish selling out of the institution to the most shortsighted economic interests. Departments and faculty members have been bending themselves out of shape for decades trying to fit into the new order while somehow maintaining their integrity. All that’s happened is their programs have been ruined, their students cheated, and their own potential as scholars compromised.

Mediocre schools, mediocre society

Over a hundred years ago, Max Weber could see the modern administrative university taking shape and understood its meaning. Large institutes had become “state capitalist” enterprises run by bosses who considered the institution theirs and acted accordingly. Faculty were merely workers who lived a “precarious ‘quasi-proletarian’ existence.” And this applied not only to the sciences, in which the means of production were already so expensive that no professor could dream of owning them, but was also quickly spreading to the humanities and social sciences.

In the new university, the “animating principle” of the old had become an “empty fiction.” And so too had its traditional priorities. Weber’s analysis of its consequences is a description of what we are witnessing at Laurentian today. The need for increased revenues led to popular subjects and “crowd-pleasing” teachers to boost enrollments at the expense of real scholars and scholarship. Educational value plummeted while the money rolled in. The result was a culture of mediocrity at all levels of the institution. For Weber, the outcome was inevitable once profit had become the measure of programs and faculty, and the corresponding psychology had taken root in the institution.

The great material prosperity that was promised if we integrated the curriculum with capital markets has not emerged, however. Rather, the situation has worsened dramatically in recent years. Levels of income inequality in Western nations are unprecedented today. In 2019, Canada’s top CEOs made 202 times what the average Canadian worker made; in the 1970s, it was forty times. Between 1978 and 2018, CEO compensation in the US rose by 940.3 percent, while a typical worker’s wage grew by 11.9 percent. I don’t have a degree in economics, but it seems pretty clear we’re being played. The only thing the “alignment of postsecondary education with labour market outcomes” has done is to ensure that we’re all dumber, poorer, and more unequal than we were even fifty years ago. Are we really going to fall for the banana in the tailpipe again?

So much for the great jobs that administrators and politicians promised if we’d only do as they say and sell out ourselves and our universities. Instead, precarious, underpaid work, for which little actual knowledge is required, is the order of the day. Even college and university courses are being quietly routinized by tech companies that know a market when they see one. In some courses, real professors have become all but unnecessary, as Weber had foretold. Only we’ve overcome the need for the crowd pleaser, who was too expensive anyway, and boring compared to Netflix. All that’s required now is some functionary to look at the rubric, count the number of boxes ticked, and hit the save/grade button. Imagine how much a course like that could make? You wouldn’t even have to write your own assessments. They’ve got a machine for that.

To complete the destruction, universities are now being bribed by the provincial government to create micro-credentials—short run courses that generate specific sets of skills and competencies but do not involve comprehensive knowledge of a field, program integrity, or engagement with other disciplines through elective courses. Universities are so pressed for money they might take the bait. And then our students will truly know nothing. No literacy, no historical context, no meaning or analysis of events. Just enough “critical thinking skills” to judge the critical distance from the kitchen to the couch, where they’ll be entertained by something they did not make and eat food they did not cook, while paying for these small pleasures with the universal basic income they did not earn because, well, who needs them anyway?

Remember Radiohead’s song “Fitter, Happier”?

Fitter, healthier and more productive

A pig

In a cage

On antibiotics

Keep on clicking

In an age in which TV shows are called Big Brother, doublespeak is routine, digital surveillance and manipulation of preference are ubiquitous, and people have largely acquiesced to constant machine oversight of their lives, it’s hard to terrify anyone with images of administrative control, the eradication of free inquiry, or the marginalization of the human personality. The New York Times tried a few years ago, with a series of articles about phone tracking and surveillance. The response from readers was a resounding “meh.”

Modern technological civilizations may not be totalitarian, but they are totalitarianish. They operationalize life, seek conformity rather than character, and elevate function over thought and action. But there are no longer any visible signs of oppression, no police or government agents peering around corners. They’re still peering, of course, in shocking, unprecedented ways. That’s the arrangement: we click, they peer. But you can click whatever you like, because the algorithm’s creators, unlike twentieth-century totalitarians, have overcome the problem of ideology, or content. It doesn’t matter what you see or think anymore, just as it doesn’t matter what you learn, so long as you keep clicking. And on that front, tech companies leave nothing to chance. Under cover of COVID, the noose is tightening. Biometrics at the border, Zoom health, and the digital campus. The system is now so ubiquitous and economically entrenched that reality has ceased to pose an appreciable threat to it. As my students say, that is because there isn’t anyone there anymore.

People like Haché, Romano, and the Laurentian board didn’t create today’s world, but they serve it, even if unwittingly. They’re transmogrifying the university curriculum in order to prepare young people to assume their place in it. So, out with the science and humanities programs—some fifty-eight of them at last count—that don’t make a buck. But that’s just the little lie. The big lie is that they are slowly destroying any seat of independent judgment within the society, particularly one that might be inclined to question them about the crappy, meaningless lives they’re preparing us for.

Our forefathers and mothers were wiser than us. They built places within the society—universities, theatres, museums—that society was told to keep its hands off of, because they knew that life is greater than society and that no society is good. Because we are unwise and because we recognize no order but our own, we are systematically destroying such places. And those whose responsibility it is to protect them are leading the effort. No more statespeople looking out for the common good, no more university presidents jealously guarding their institutions’ curriculum, students, and faculty. Just toadies for tech, willing to sell out for the most myopic ends and by means of the most vulgar devices.

We should try to remember who we are and what we have lost before they finish the job and the last physics or midwifery or politics course is gone. We are not obliged to be silent. And if they will not listen, we must not lose heart. We can talk among ourselves and try to begin again.

Ron Srigley is a writer and academic. His work has appeared in The Walrus, The Los Angeles Review of Books, L’Obs, and the MIT Technology Review, as well as in scholarly journals. He teaches in the School of Liberal Arts and Sciences at Humber College, Toronto. He is author of Albert Camus’s Critique of Modernity, Eric Voegelin’s Platonic Theology, and translator of Albert Camus’s Christian Metaphysics and Neoplatonism.