State files confirm targeted RCMP violence in the aftermath of 1969 Sir George protest

Federal police used tactics to divide and discredit Black organizations in Canada

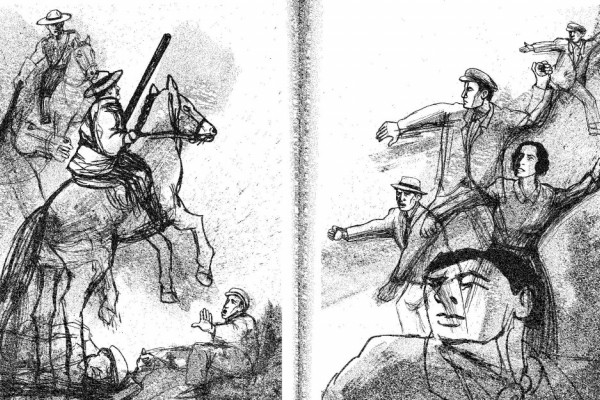

Students during the 1969 Sir George Williams University student protest. Concordia released an official apology for its mishandling of race-based student complaints in October 2022. Photo courtesy Concordia University.

When Concordia University issued a public apology last October for its role in the 1969 student protest at Sir George Williams University, it acknowledged the many acts of institutional racism that led up to the landmark protest, including the university’s role in involving the police to quell the demonstration.

Over 50 years later, details of RCMP violence aimed at Sir George protesters and their allies continue to emerge through freedom of information access to state files.

The two week sit-in at Sir George William University, which later became Concordia, lasted from January 29 to February 11, 1969 and was launched in response to the administration’s mishandling of incidents of anti-Black racism.

Nine months earlier, Caribbean students from the biology department filed a complaint that professor Perry Anderson was deliberately failing them because they were Black. When the administration refused to take their grievance seriously, protesters occupied the university’s ninth floor computer centre and seventh floor faculty lounge. After a peaceful protest, police were called on the morning of February 11, 1969. A fire then broke out, destroying the computer centre and ending the sit-in.

In the aftermath, 97 students were arrested, and formal charges were issued for mischief and obstruction of private property, causing lengthy criminal trials.

53 years ago, on 29 Jan 1969, six Black West Indian students at Sir George Williams University, Montreal, alleging racial discrimination, led an occupation of the computer centre. On 11 Feb it was severely damaged as police entered; largest student occupation in Canadian history. pic.twitter.com/0dgbLUy8u8

— Wayne Chen (@wcchen) January 30, 2022

The Sir George uprising occurred amidst the backdrop of the 1960s, when the RCMP was acting preemptively against fears of New Left and socialist movements, especially those situated at universities. One briefing describes the student occupation at Sir George as unrest that “will terminate in a communist dictatorship of the proletariat that will be more fascist than even that of the Nazi regime in Germany during World War II.”

In response to this Cold War fervour, the RCMP established a “racial intelligence program” to disrupt the organizing efforts of Caribbean students and activists connected to Sir George, and those who identified with Black power and Black nationalist movements.

In an aide-mémoire submitted to a public inquiry for RCMP abuses, Assistant RCMP Commissioner Stanley Vincent Maurice Chisholm gave detailed examples of tactics used to divide and discredit Black organizations in Canada and their leaders, specifically Rosie Douglas and those close to him. Douglas was one of the leaders of the Sir George occupation, and would go on to become the prime minister of Dominica, a small Caribbean island nation.

Targeted activities included pouring a chemical agent into the gas tank of Douglas’s car that would prevent him from driving it, and forcing him to ride in an informants’ car instead, where he and others could be recorded. Chisholm wrote about how the objective of this operation was “to discredit Douglas as a leader within the Black community and factionalize an already shaky alliance of Black groups.”

The operation also included the issuance of a death threat to community worker and Dominican national, Nathalie Charles, by an RCMP agent. RCMP officials would later stage a “rescue” of Charles at her apartment, advising her that they were aware of threats being made against her life and offered her protection and assistance to leave Canada.

“This was engineered to get one more organizer out of the way. And in this case not only was I an organizer, I was also calling out an agent provocateur as an imposter. This is where the motive for the death threat likely came from,” said Charles from her home in Dominica. Charles never returned to Canada, and was forced to abandon her academic pursuits because of the incident.

These events occurred in 1972, a time when violent threats against Black life in Toronto were so prevalent that a coalition of local Black organizations set up a community defence force. This was in response to months of racial terror that included threatening letters supposedly penned by the Ku Klux Klan, racist slogans painted on the windows of Third World Books (an icon of the Black cultural renaissance in 1960s Toronto), and the burning of a Jamaican-Canadian community centre.

The proximity of the RCMP to these events through the use of informants can be traced right back to the Sir George Williams occupation, including the time of the fire. An RCMP briefing from March 1969 described how “the infiltration of Sir George Williams is an example of what’s happening in universities throughout North America.” Within this briefing, reports following the February 11 fire and the 97 arrests remain heavily redacted.

“Many students including myself were beaten and tortured by the Montréal Police. Students were forced to lay down on broken glass on the floor and were beaten with clubs,” recalled Lynne Murray, one of several veteran protesters who spoke during the public apology event at Concordia last October. “One of the students from the Bahamas suffered a brain aneurysm, and she died shortly after. Her parents believe she died because of the actual beatings she received that day.”

Rosie Douglas was deported from Canada in 1976 after being deemed a national security threat based on an alleged RCMP report of an arson conviction—but Douglas was convicted of obstruction of the use of private property, not arson. Following numerous attempts by Douglas to testify before the MacDonald Commission of Inquiry into Certain Activities of the RCMP to challenge and correct this record, all of his requests were denied.

Anne Cools and Brenda Dash, who received convictions for mischief from their involvement in the protest, later submitted applications for a pardon from the Queen. With consequences concerning employment, international visas, continued academic education, and mental health impact for many veteran protesters, it is ironic that a pardon from the Queen be the sole remedy to expunge criminal records that were dictated by counterinsurgency tactics and the repressive violence of the Queen’s agents and the Canadian state—which remain unaccounted for.

At a time when institutions like Concordia University are now attempting to repair the harms they caused to Black communities and organizations involved in the 1969 Sir George occupation, when will the Canadian state acknowledge its role in manufacturing anti-Black violence during the occupation, and the continuum of harm and racial terror committed by the RCMP that followed?

Andrea Conte is a researcher, media artist, and author of a recent Briarpatch article entitled “Administrative Sabotage: Censorship of Canada’s State Archives.” Philippe Fils-Aimé is a writer and veteran organizer who participated in the Sir George occupation.