Social conflict is inevitable in decolonization battle

Members of Unis’tot’en camp, November 2012.

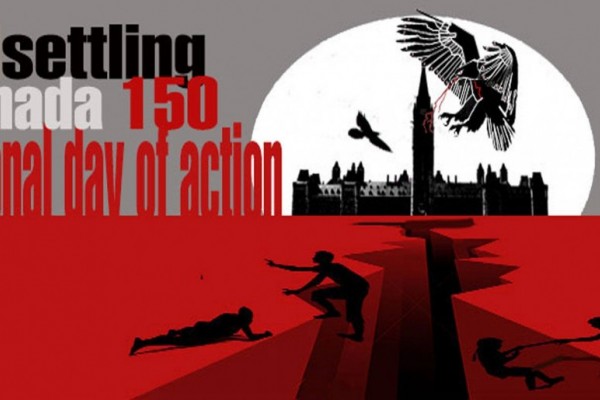

All the controversy over Canada 150 and its morbid celebration of the gains Canada has made at the expense of Indigenous lives has many people asking: What do we do now? What will the next 150 years look like? We all know that Indigenous Nations on Turtle Island have experienced some of the most prolonged and violent genocidal acts in the world. Canada was colonized with such lethal force that millions died as a result, all in the name of unearned power and wealth. State colonization continues through Canadian laws and policies, decisions of government officials and enforced by Canada’s police and military forces. Another powerful threat is corporate colonization; the way in which large corporations heavily influence governments and violently colonize Indigenous bodies, lands and waters. So, how do we decolonize in the face of continued colonization?

If we are going to decolonize, it must be done with full awareness of what must be done and with full preparedness for the discomfort that comes with it. It requires speaking the truth about our collective history but, more importantly, about how that history continues to impact our current reality. This will not be easy. Most social justice activists and Indigenous resistance activists can speak to the loneliness of being the only person in a room trying to draw attention to potential threats to our nations, when most would prefer to not engage in difficult conversations. But here’s the reality: in the history of human beings, real social change has never come without some level of social conflict. Indigenous peoples can attest to this as we have had to fight and push for every single right or freedom we have today.

Decolonization won’t happen without social conflict either. We know this from our collective histories, the many painful experiences of our peoples and the long trail of empty words and broken government promises. Our ancestors would never have survived without their collective strength and unity in resistance. Any gains we have made as Indigenous Nations have been won through acts of withdrawal, resistance and determination. We have survived every attempt that colonial and Canadian governments have made to eliminate us from our own lands — including scalping bounties, smallpox blankets, rapes and murders of our children in residential schools, forced sterilizations of our women and starvation tactics. We simply wouldn’t be here if we didn’t strenuously resist assimilation at all costs, but we have suffered many losses as a result. It is therefore critical that we forgive ourselves for the many ways in which we have been colonized and find ways to lift one another up.

While much focus has been put on the resistance side of decolonization, we cannot forget the importance of resurgence and revitalization. Were it not for those brave children in residential schools who spoke their languages or practiced their ceremonies in secret, we’d have fewer people today to help revitalize our cultures. There are literally thousands of people in our First Nations working to teach our children their languages, teaching them how to live on the land and passing on our traditions, practices and ceremonies. Every time someone speaks their Indigenous language, helps take care of our elders, or raises loving, healthy children, they are both decolonizing and nation-building at the same time. Making sure our efforts are balanced is what will help us move forward in the next 150 years.

Going forward it will be critical for us to withdraw from all government and corporate tables, committees and negotiation processes that do not serve our best interests and respect our rights. It also means we have to continue to adapt our tactics as needed and engage in diverse acts of local, regional and national acts of resistance in multiple forums and help support those engaged in different ways. Resistance can be blockades, rallies, public education, media outreach, legal advocacy and litigation, and/or political pressure domestically and internationally. We will have to give less energy to online trolls and detractors and focus more on spreading our core messages. It’s time national leaders stopped settling for land acknowledgements and started demanding land transfers.

In the end, decolonization will require effort on the colonizer’s part as well. If there is to be peace on Turtle Island, Canadian governments will have to go beyond superficial words and gestures and take substantive action to address our rights. Until then, if being Indigenous, protecting our lands and waters and exercising our Aboriginal and treaty rights means we are breaking Canadian laws; then we need to continue to be “criminally Indigenous” for the sake of our future generations.

Pam Palmater is a Mi’kmaw citizen and member of the Eel River Bar First Nation in northern New Brunswick. She has been a practicing lawyer for 18 years and is currently an Associate Professor and the Chair in Indigenous Governance at Ryerson University.

This article appeared in the Summer 2017 issue of Canadian Dimension (Canada 150).