Sam Gindin on Leo Panitch

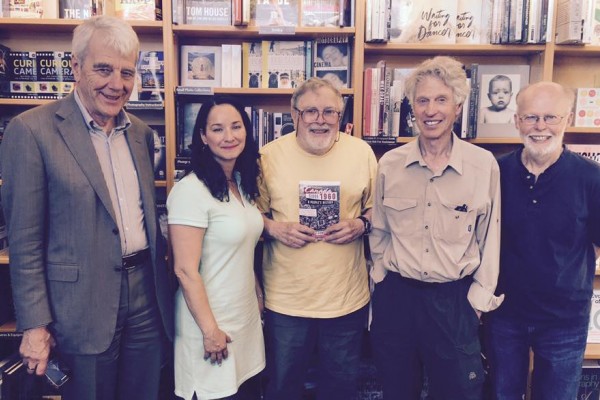

Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin, lifelong friends, comrades, and collaborators.

In this wide-ranging interview, members of the Canadian Dimension editorial committee spoke with Sam Gindin, a lifelong friend, comrade, and collaborator of Leo Panitch, about their relationship and how Leo’s views and perspectives changed over time.

In 2012, Gindin and Panitch published The Making of Global Capitalism: The Political Economy of American Empire, which was awarded the 2013 Isaac and Tamara Deutscher Memorial Prize. The book traces the development of American-led globalization over more than a century.

Most recently, Panitch, Gindin, and Stephen Maher published The Socialist Challenge Today: Syriza, Corbyn, Sanders a newly updated and expanded primer for twenty-first century democratic socialists.

Gindin is a Canadian academic and intellectual who served as research director of the Canadian region of the United Auto Workers (UAW) union and later as chief economist and Assistant to the President of the Canadian Auto Workers (CAW) union after the latter became independent from its American parent organization. He is a long-time contributor to CD.

Working with Leo

How did your unique collaboration with Leo come about? How was it working with him so closely and over such a long time? Did you develop some particular way of working together? Some division of labour?

Leo and I met in 1962 when we were both 17 and in first year at the University of Manitoba (at that time you could do so after Grade 11). We became close friends immediately and stayed in touch over the next couple of decades even though we lived in different cities and had different careers. In 1984 Leo came to Toronto to teach at York; I had already been in Toronto for a decade working with the CAW (now Unifor). We each altered our understandings and politics over the years, but it was fascinating to discover that we kept moving in the same direction.

Our discussions in Toronto revolved primarily around worker struggles and the limits of social democratic politics. I especially appreciated the extent to which Leo forwarded articles for me to read and challenged me on what the autoworkers were or were doing or not doing and his exhorting me to stretch the limits of my job and of the union.

“Ok Gindin,” he’d say, “Chapter 4: what’s the first sentence.” I’d look at him blankly and he’d write it himself then, sometimes in a matter of fact tone, sometimes crabbily, he’d demand the second sentence. We worked in his study and generally shmoozed for a couple of hours before reminding ourselves that we should be writing something. But seeing it was too close to lunch to start, we moved to lunch and continued to shmooze over sardines or leftovers from a meal he or Melanie had cooked the day before, but the talk now shifted to the task at hand. On good days we usually managed to get a couple of good hours of writing in, though it wasn’t unusual to modify it beyond recognition the next day.

At one point, the writing was going slowly; after a couple of years we were only up to 1945 in our narrative and we were determined to break the impasse. We decided to go to the cottage he and Melanie shared with some friends but was then empty for a while. When we came back six weeks later, we were in the late 1920s. In our absence our two families had Thanksgiving dinner together and at one point one of my and Schus’s sons solemnly declared: “You all know, don’t you that Leo and Sam finished the book a long ago but are just faking it so they can keep hanging out together.”

Leo and I had different skills—he a political scientist working in academe and I an economist grounded in the union—but we generally didn’t divide up the work that way. We discussed state theory, the political economy of empire and history together as we wrote, him on his computer, me in an easy chair he had bought to ease my bad back. I had more catching up to do on some of the academic literature that Leo taught regularly in his grad courses; Leo left the graphs and tables to me but never deferred to my economic arguments—where we disagreed, he had to be convinced.

Marxism

Can you go back a step and elaborate on how you and Leo became Marxists?

We were both affected by our history—the place we grew up, the time, and the interactions with mentors—towards a leftish sensibility. We grew up in North End Winnipeg, which had a rich immigrant and socialist subculture; socialism of various kinds was ‘in the air.’ We then started university in the 1960s and were affected by the civil rights movement in the US, the worldwide protests again the US war in Vietnam, and Canadian left nationalism, each part of a youth rebellion against the status quo. A small undergrad seminar with Cy Gonick, very influential in getting us to think more formally in terms in class and power, opened both of us to radical thinking.

In the middle of another class—Leo claimed it was an economics class, I remember it as Latin class—Leo turned to me and whispered, “I think I’m a Marxist!” He had just read the preface to Marx’s A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, which was an early outline of Marx’s historical materialism. But the development of our Marxism waited until we were in grad school, with Leo taking a life-changing class with Ralph Miliband. In retrospect, Leo thought that previous to meeting Miliband, he might very well have gone into law or public administration. My own formal Marxist analysis and politics came from study groups set up with fellow students, sitting in on radical lectures by Harvey Goldberg, and a sociology seminar with Maurice Zeitlin. Leo became a lifelong friend of Miliband’s and later a co-editor with Ralph of the Socialist Register.

Understanding US empire

What role did Leo’s understanding of Canada’s political economy play in his theory of how US led imperialism governed the world economy?

It was common, from the post-war years on, for the left to argue that Canada’s economic and military dependence on the United States had led to its loss of ‘sovereignty’ and that globalization now generally bypassed states. Leo however grasped—basing himself on Canadian experience—that the Canadian state retained its sovereignty but used it to create the conditions for attracting American capital. And in the case of the free trade agreement with the US, Leo noted that the Canadian state wasn’t a ‘victim’ of freer trade (dragged into it by the US), but an author (anxious to secure both exports to the US and the continued flow of US investment into Canada).

That is, the Canadian state still mattered very much but it was now ‘internationalized’ in the sense of its role being the creation of the conditions, within its own borders, for supporting global accumulation (think of its treatment of GM for example). Moreover, it was not the Canadian state whose sovereignty was being threatened—after all, the Canadian state’s main ambition was to be a junior partner of American empire—but that of those sections of the population that had another vision in mind. The tighter economic integration into the US and the constitutionalizing of property rights through free trade agreements limited what a democratically elected progressive government might do.

The Canadian experience was also suggestive of the emergence of a new kind of empire. The new empire was no longer based on direct territorial control (colonies). Nor was it based on a fragmented capitalism of competing empires. Rather, it accepted national sovereignty, was officially against any formal empires, and was evolving into a global capitalism that was increasingly inclusive of all capitalist (and working).

The US certainly had a special role in this empire, but this was an informal empire with the American state playing a superintending role: it mediated the development of trade agreements and free capital flows, influenced the overall legal framework even generally accepting that the rules also applied to itself, supplied global capitalism with an international currency and based on the US dollar the US Fed effectively acted as the world’s central bank. The American military role did of course not disappear, but it was now not primarily geared to obtain special privileges for the US but rather to keep this global system functioning, stable, and expanding.

Interestingly, as Europe became more deeply integrated into the American empire, this process was often described by the Europeans as ‘Canadianization.’ In part it expressed the dependence of other capitalist countries on the US but more than that, especially as these other countries developed within the American umbrella, the dependence, it became clear, was not just on the US but on a new world order overseen by the US.

This put to rest (or at least should have) expectations of ‘inter-imperial rivalry.’ Tensions between countries remained, but the depth of their mutual integration—Germany investing in the American South, China more dependent on foreign markets and technology than any major country had ever been, Asian suppliers meeting US demands—created the material basis for each state wanting to see the global economy reproduced (albeit modified from time to time).

Leo was not a Canadian nationalist in the sense of supporting the Canadian bourgeoise against the Americans. But he also argued that any socialist revolution was necessarily also a nationalist project. Though the internationalization of the Canadian economy was always justified in nationalist terms as being key to Canadian development and prosperity, Leo noted that the prospects of an alliance between the left and the Canadian bourgeoise in the name of Canadian development had nowhere to go. The extent of the integration of the Canadian capitalist class into the American empire was so profound that there was simply no way that Canadian capitalists would flirt with left nationalists. Canadian capitalists were, in fact, more likely to come down on left nationalists long before we had to worry about American intervention.

Such understandings—the internationalization of the state and the state as the prime site of struggle as opposed to struggle having been shifted to some ethereal international space—were fundamental underpinnings of The Making of Global Capitalism. Later, we began to work through how globalization was primarily legitimated not through not international institutions or the American state but, as in Canada, through nation states themselves selling the benefits of continentalism, and so a form of nationalism co-existed with the internationalization of the economy.

L-R: Greg Albo, Sam Gindin, Leo Panitch. Photo courtesy Socialist Project.

Internationalism

Where then did internationalism fit into this state-centered view of the world?

Socialism is universalist; there can be no socialism without it being an internationalist vision. On the other hand, organizing must of necessity be local and political change must first address the domestic state.

Absent a powerful working class movement at home, there were limits to what could be done to advance struggles elsewhere. If private sector and public sector workers weren’t in solidarity at home, if autoworkers and steelworkers were divided in Canada, it is hard to imagine them being all that effective in showing concrete solidarity with other workers far away, with their own cultures and facing such radically different contexts. Nor could we, if we didn’t control technology at home, decide to share it with others abroad, nor cancel their debt if we weren’t strong enough to even modify debt dependence in our own country.

Internationalism—as a practice and not just as a slogan—therefore meant for Leo that we must of course do everything we can to prevent the interference of our own governments in the democratic decisions of others abroad and that the planetary implications of the environmental crisis obviously demanded international responses. But he especially emphasized two points.

First that struggling at home and challenging capital where we can is so crucial because it creates the space for workers in other countries to go further in their own struggles (the corollary being that accepting concessions where we are undermines workers elsewhere). Second that passing on our own knowledge and experiences and learning from struggles elsewhere is one of the most aspects of socialist internationalism. Among other things this means doing solidarity work that does not limit itself to cheerleading, but soberly assesses ‘experiments’ elsewhere so their mistakes as well as their breakthroughs can contribute to building the kinds of movements that can be more successful in the long struggle to overcome capitalism.

It was in this context that Leo was so often hosted by movements not only in the UK and the US but in Greece, Turkey, Brazil, Argentina, Nicaragua, India. He was on a mission to share his knowledge (democratize knowledge), learn from their experiences and also challenge them in a respectful, comradely and solidaristic way.

Shifts in thinking?

Did Leo change his mind about anything politically significant over the last 10 or 15 years?

Did the seeming early success of Corbyn and Sanders inside the Labour and Democratic parties cause Leo to reconsider his long held view, shared by Canadian Dimension, that these social democratic parties can never be transformed into parties with the capacity to challenge and defeat capitalism and become vehicles for building socialism?

Leo was a historical materialist and took the ‘historical’ aspect of this seriously. Things change and so must our analytical categories and our strategies. Strategies are inherently conjunctural: they depend on time, place and the balance of class forces. The question of Leo changing his views is most often raised—as you do here—in regard to Leo’s attitudes to Corbyn and Sanders.

Leo did not, as some have argued, change his take on social democracy. He never believed that social democracy was interested in, or might become committed to, the making of a working class with the vision, confidence and capacities to end capitalism and create socialism. He was truly excited by the Corbyn and Sanders phenomenon; he saw them as part of a crucial shift from protest to politics and as finally opening space for rejecting neoliberalism, a socialist discourse, and a political explosion of a new generation entering politics. He saw his role as encouraging and supporting these developments. But privately at least, in discussions with Left activists, and perhaps more cautiously in his writings, he retained his rejection of social democracy as ‘the answer’.

It’s true that getting actively engaged with these movements, especially with Corbyn and Momentum (the movement that supported Corbyn) Leo did often express a greater optimism in the possibility of radical change. But this could only come about he insisted through a split in the Labour Party, not its democratic conversion; either the right would leave or it would kick the left out. The role of the Labour left in this context, he argued, was to use their presence in the party to build the kind of base in working class unions and communities that could be ready to move beyond social democracy when the time came. This raises some difficult questions which Leo’s comrades are still debating among themselves.

Syriza

Leo was close to the leadership of Greece’s left-wing party, Syriza, which came to power on an anti-austerity platform in 2015. Within months of taking power, however, Syriza’s leader, Alexis Tsipras, ignored the result of a Greek referendum on austerity and agreed to adopt harsh economic measures demanded by Greece’s creditors. Did Leo’s views about Syriza evolve over time and if so how?

Leo noted that Syriza was the first party in a developed country to get elected to national government on an anti-neoliberal platform. He saw it as more than a traditional social democratic party and though he put great hope in it, he was also fully aware of its weaknesses and the barriers it faced.

The most important point however—and this was something Leo raised from the very beginning—was whether the Greeks were ready to risk a break with Europe. If not, then they had no real negotiating power or options. As a party, Syriza was itself powerfully committed to staying in Europe. But so was the party base and the working class according to all polls. Its in this context that the ‘NO’ vote needs to be understood. Tsipras did not ask whether Greeks were ready to leave Europe if necessary but whether they refused concessions. Syriza mobilized successfully against concessions but its enemies on the other side of the table knew that they were not ready to leave Europe so they simply ignored the vote.

The other crucial factor, and the one that charging Tsipras with ‘betrayal’ avoided or at least obscured, was the challenge of having to govern a capitalist country at the same time as the party also mobilized the base outside the party. The latter is difficult enough because the wing of the party more concerned with re-election can be expected to be more conservative yet it is backed by the legitimacy of it having won the election and controlling critical levers of the state.

As it turned out, however, this tension was never really pushed, not even by Syriza’s most left-wing activists; the movements Leo and I talked to while in Greek argued that while there was sympathy for them in Syriza and some cooperation around demonstrations, the daily links between them and Syriza cadre (e.g. in obtaining and delivering food and medicine) were minimal. And Syriza’s base in the unions was very weak.

For Leo, I think what he learned most from this experience didn’t revolve around whether Syriza had sold out but how unprepared they were for carrying out the struggle in the workplaces (over, for example, factory closures), in the communities and in the state. Coming to government was not the revolution; the revolution began rather with transformations in the state so it could support mass organizing and the deepening of democracy in civil society communities.

Ecosocialism

To our knowledge, Leo spoke little of ecosocialism. In what ways, if any, did the looming ecological breakdown inform his analysis of global capitalism and shape his socialist imagination?

Like other socialists of his generation, the environment was an important issue but often subsumed under fighting capitalism. Nevertheless, the Socialist Project, which was Leo’s political home for decades did see itself as an ‘ecosocialist’ grouping and beginning with the 2007 issue, “Coming to Terms with Nature,” edited with Colin Leys, the Socialist Register paid increasing attention to ecology issues (in both the Socialist Project and the later issues of the Register Greg Albo was very influential in the environmental turn).

Leo was very concerned that ‘catastrophists,’ though obviously justified in their concerns, couldn’t point to the scale of the problem and then declare we only had a decade or two to resolve it. If ‘resolving’ the ecological crisis and fixing the damage already done meant going beyond a society based on fragmented capitalists competing for private profits and a working class culture based on material compensation for the deformation of their productive potentials then this couldn’t be done in a couple of decades or even most of our lifetimes.

This contradiction between the time scale of capitalism and the time scale of the environment could not be brushed aside. It would, Leo understood, bring us a very ugly world before we could turn things around, including the mass migration of people intersecting with national frustrations and nativism. All this made the winning of socialism more important than ever yet also complicating the eventual making of a new world.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.