Queers against apartheid: From South Africa to Israel

Simon Tseko Nkoli (1957-1998) was an anti-apartheid, gay rights and AIDS activist in South Africa.

Twenty-five years ago I used to compile the international news for The Body Politic, at the time Canada’s leading gay and lesbian liberation journal. In the winter of 1985 I was sifting through the piles of newspapers, journals, and newsletters that we received every month and I noticed a small article in a newsletter from Scotland.

The article talked about a young anti-apartheid activist who was being held in solitary confinement and who had just come out as a gay man.

Simon Nkoli

Anti-apartheid activism was a major current in progressive organizing in Toronto in the mid 80s so the story immediately piqued my interest. I contacted the Toronto Committee for the Liberation of South African Colonies (TCLSAC) and got the number of a member who had returned to South Africa. He was able to put me in touch with someone who was in contact with this young man, Simon Nkoli.

Simon was one of the Delmas 22, most of whom were members of the United Democratic Front. The UDF was the major legal anti-apartheid organization since the African National Congress (ANC) had been banned as a terrorist group. The UDF had been central to organizing protests against arbitrary rent hikes in the African townships surrounding Johannesburg. Most of the protests had been peaceful, but violence had broken out on a number of occasions and there had been several deaths. In September 1984, the South African police attempted to crush the ongoing protests and swooped down on key organizers, arresting twenty-two. The prisoners were held in solitary confinement until they were finally charged with treason and murder in January 1986, charges that could carry the death penalty.

Simon had been a leader in both the Congress of South African Students and the UDF. He was also a gay man and had joined the fledgling Gay Association of South Africa (GASA) in 1983. GASA, ostensibly a multi-racial group, was overwhelmingly white in practice. Meetings, for example, were usually held in white only areas. Simon was disturbed by this and organized a support group that met in Soweto on GASA’s behalf. The Saturday Group, as it became known, was overwhelmingly black.

But until he was imprisoned, Simon had kept these parts of his life separate. It was in his cold prison cell in the winter of 1984-85 that he decided it was time to challenge the apartheid of issues and struggles, and so he began the process of coming out to his co-defendants.

The Body Politic’s reports on the case inspired a number of local queer activists, and in early 1986, about a dozen of us came together and formed The Simon Nkodi Anti-Apartheid Committee. SNAAC provided Simon with emotional and material support. Prison was very hard. We corresponded regularly, arranged for subscriptions to LGBT magazines, publicized his case, and sent him the news clippings to let him know that people around the world were supporting him. Later, in 1988 when he was finally released on bail but couldn’t work because of the ongoing trial, we helped pay his rent.

But the lion’s share of our activity was to do anti-apartheid work in Toronto’s LGBT community and anti-homophobia work in the anti-apartheid movement. Our banner became a regular fixture in anti-apartheid rallies, International Women’s Day, and LGBT events. We organized a night of queer performance art as part of the city-wide Arts Against Apartheid festival in 1986. We sent out press releases to the LGBT and straight press about developments in the trial. We helped out with ANC picketing and leafleting. We put pressure on GASA to take a stand on Simon’s case through the International Lesbian and Gay Association (ILGA). And when Simon was finally acquitted, we organized a North American tour in 1989. He visited something like twenty-five cities in as many days. When he spoke in Toronto he was on the front cover of NOW magazine. His tour was an important boost for anti-apartheid work on the continent.

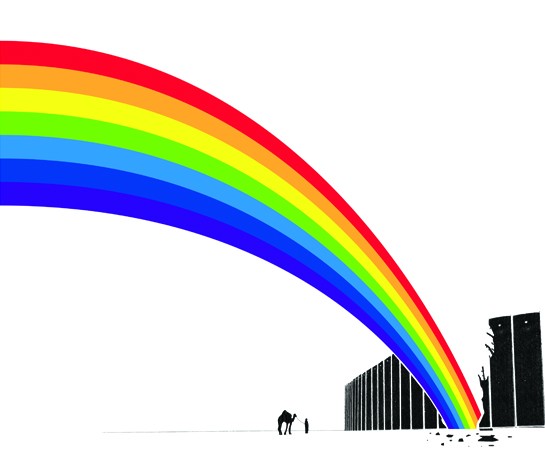

Illustration by Elle Flanders

But if we had work to do, things were much harder for Simon. First, he faced complete indifference from GASA. The group argued that since he had not been arrested on gay related charges, this was not a gay issue. GASA couldn’t get involved in politics that were outside of its mandate.

On the other hand, in prison Simon continued coming out to his co-defendants. There, a mix of Christian fundamentalism, African traditionalism, and Old Left prudery and sexual conservatism made it an uphill battle. But he persevered, and soon the other prisoners, starved for news of the outside world, were reading the gay magazines we were sending him, and marvelling at the international support he was getting.

Terror Lekota, now National Chair of the ANC, and then a Delmas co-defendant, recalled that despite initial hostility, “All of us acknowledge that Simon’s coming out was an important learning experience … How could we say that men and women like Simon, who had put their shoulders to the wheel to end apartheid, should now be discriminated against?”

Simon spoke about the experience during his 1989 tour.

My co-defendants came to me and said they didn’t realize gay people could be so concerned about apartheid. Of course they didn’t! How would they know in South Africa if all of us are in the closet? There are lots of gay activists involved in political organizations, but because of the pressure put upon the gay and lesbian community, we are afraid to come out. “What will people think if they know I am a gay person? I’d better fight against apartheid in a hidden way.” The danger of that is that when South Africa is liberated, we as gay people will seem never to have taken part in liberating our people. What will we say when people ask, “What did you do to bring about change in this country, where were you during the battle?” We’d have to come back to them and say, “We were with you but we didn’t want you to know we were there.” That would be a foolish answer.

We in the gay and lesbian community in South Africa are also to be blamed because those people who have come out of the closet then want to fight for lesbian and gay rights only. We must say that is not enough, because if we isolate the gay and lesbian struggle it will be the same as women isolating their struggle, or the youth, or workers, and then everybody will have lots of struggles within apartheid. So let’s bring all these struggles together, as we are doing, and united we will go somewhere. When South Africa is liberated, there will be no question of anyone saying, “those people were not part of us.”

Simon’s words turned out to be prescient. His coming out set in motion a chain of events that culminated in South Africa’s new post-apartheid constitution being the first in the world to prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. This was a huge step for LGBT rights in Africa. When he visited Toronto, Simon also made contacts with AIDS Service Organizations and returned the next year to study their work. He took that experience back to South Africa where he helped found one of the country’s first ASOs, the Township AIDS Project.

At his funeral in 1998 a number of his comrades came together and began the work to found the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) which is today still probably the world’s largest and most vibrant AIDS activist group. Its campaign to force the Mbeki government to roll out anti-viral treatments to people with AIDS saved millions of lives. It is with some satisfaction that I can say that we in Toronto, in supporting Simon during his difficult years in prison and afterwards, played some small part in that process.

A new apartheid

Now, two decades later, we find ourselves confronted with a new apartheid, in Palestine. The scenario is familiar: human rights abuses, separation of peoples, displacement, armed resistance, military repression, biased media, and a growing international solidarity movement. I won’t try to make the case for the similarities on the ground in Palestine and the use of the term “apartheid” to describe it. A new report from the Human Sciences Research Council of South Africa entitled Occupation, Colonialism, Apartheid?: A re-assessment of Israel’s practices in the occupied Palestinian territories under international law makes that case far more eloquently and in far more detail than I can here. Let me quote just one paragraph from the executive summary.

This study is the outcome of a fifteen-month collaborative process of intensive research, consultation, writing and review. It concludes and, it is to be hoped, persuasively argues and clearly demonstrates that Israel, since 1967, has been the belligerent Occupying Power in the OPT, and that its occupation of these territories has become a colonial enterprise which implements a system of apartheid.

If there is anyone in the world who should know what apartheid is, it is the South Africans.

Illustration by Galen Johnson

What I want to focus on are the striking similarities in the discourses we heard about South Africa in the mid-eighties and what we are hearing about Palestine today, here in Canada. South Africa portrayed itself as a multi-party liberal democracy in a region of backward authoritarian states, as does Israel. South Africa touted its prosperity in contrast with surrounding poverty and underdevelopment, as does Israel. South Africa cast itself as the victim surrounded by a continent of savage and dangerous enemies, as does Israel. In both cases this victimhood was/is used to justify an exceptional status and the need to be ruthless. In both cases we hear that no one who doesn’t live there could possibly understand. “Why don’t you focus on the human rights abuses in the surrounding African countries?” said the South Africans. “Why focus on Israel?” says the Israeli government. And the answer to that rhetorical question is also the same. Just as South Africa accused its critics of being anti-white, Israel accuses its critics of being anti-Semites.

Like South Africa twenty-five years ago, Israel today portrays itself as a progressive liberal democracy, an endangered island of modernity in a backward and hostile region. The existence of a gay rights movement in Israel is deployed as another example of this modernity.

I think that these similarities tell us a great deal, that they actually reveal the underlying process that they are designed to obscure—a common colonial project.

Such stories of embattled modernism are not narratives exclusive to either South Africa or Israel. They are in fact part of a common vocabulary of European colonialism since the beginning. But since colonial projects, despite their modern rhetoric, involve plunder, violence, and dispossession, they must also develop a narrative to explain why the “other” must be plundered, brutalized, and dispossessed.

What stake do queers have in anti-colonial struggles?

Today, one would have to be deaf and blind not to recognize the growing racism within Israel as a result of that country’s colonial practices in the occupied territories. One cannot terrorize, brutalize, dispossess, murder people like yourself. The other must be vilified. They must become less than human.

Which brings us to the question—what stake do queers have in anti-colonial struggles? What stake do we have in what is going on in Palestine?

This is not a simple question. We are children of the modern world. For discernable social and economic reasons, we have emerged as a voice, as an identity, first and foremost in modern industrial (or postmodern, post-industrial) societies. And we have utilized the values associated with these societies—individual freedom, human rights, democratic participation, equality, secularism, rationality—as tools in our fight for rights and recognition.

This makes it easy for our community to identify with societies, like Israel, that resemble our own, and easier to be complicit in the wilful blindness towards what is going on in the Occupied Territories, since we too are the result of a colonial project. We too have built our society on stolen land.

That means that our solidarity work needs to be strategic, thoughtful, and patient. It means that solidarity is more than just sympathy for victims. We need to understand what is going on there because it helps us understand what is going on here, and the role of our community in a broader world.

Only when we understand colonialism can we argue with conviction that what is going on in the Occupied Territories is neither an extension nor a defence of liberal democracy. It is its negation. Democracy after ethnic cleansing is not democracy. Wealth based on expropriation is not earned or sustainable. The exceptionalism deployed to justify the horrors inflicted, and the racism that it generates, corrodes the moral and ethical character of its perpetrators and apologists. It corrodes the values that we depend on.

So when we stand in solidarity with those who are resisting the occupation, we are not betraying the values that nurtured our communities, we are in fact defending them.

Secondly, I would argue that we are defending ourselves. Queers are like cuckoos. We are born in other people’s nests. Those are nests of all colours, all cultures, all religions, all regions … And those differences shape how we define ourselves, who we feel we are, how we live our lives, how open we can be or want to be. What has emerged in my lifetime is the beginnings of a conversation across a globalized world, a conversation that is knitting together constellations of related identities that are developing connections, solidarity, mutual support. We are actually for the first time becoming a global movement.

But the major barrier to that conversation and that movement is the inequality that comes from the exploitation of parts of the world by wealthier and more powerful nations, and the racism that colonial processes generate and must generate in order to make sense of that inequality.

Our liberation is bound up with the liberation of others

If we are to survive as a global movement, opposition to racism must be central to our politics, and if we are really to oppose racism we must also oppose the colonial and imperial projects that generate it.

While this was all true twenty-five years ago when we were working on the Simon Nkodi Anti-Apartheid Committee, it is especially crucial now. Historically, since our emergence as a movement at the end of the sixties we have had the advantage of speaking from the imperial centre. That position amplified our voices, allowed them to be heard around the world (it has also had its downside, since to many parts of the world, abused by our countries, conservative forces have used our existence as a symbol of the oppressor).

Simon was able to identify as a gay man because that identity was available to him. A decade before, that might not have been the case. People have always had unconventional sex, but the idea that this might make one part of a particular group is a relatively modern notion. Gay identity was available to Simon because we had proclaimed it so loudly and so effectively, and we had proclaimed it in the dominant parts of the world.

But now history seems to be turning a page. As they say, all that was once solid dissolves into air. And that’s not just the trillions of dollars that have evaporated in the last few months as the disastrous neo-liberal experiment crashes and burns. New powers are emerging. We have no idea what the world will look like in another decade. In this turmoil we could easily be swept away as the first homosexual rights movements were swept away in the turmoil of fascism and world war in the last century.

If, whatever new world order that emerges is to be better than the old, if we are to have a place, we need to follow the path that Simon blazed for us. We need to overcome the apartheid of issues and struggles. Our movement must be not just a symbol of Western modernity or postmodernity, it must be a symbol of justice, justice for everyone.

Only an engaged, globalized movement of LGBT people can guarantee that. More than ever before, our liberation is bound up with the liberation of others. So we must stand against racism. We must stand against colonialism. If we persevere we will emerge stronger like we did in South Africa. And when the dust settles, there will be no question of anyone asking us “where were you in our struggle?” Because we will be able to say, with confidence, “we were there.”

Tim McCaskell is a long-time gay activist. He worked on The Body Politic, the Right to Privacy Committee after the 1981 police raids on gay baths, the Simon Nkodi Anti-Apartheid Committee, AIDS ACTION NOW! and Queers Against Israeli Apartheid. His first book, Race to Equity, a history of the struggle for equity in Toronto public schools, is widely used in teacher education. Tim is also the author of Queer Progress: From Homophobia to Homonationalism.

This article appeared in the July/August 2010 issue of Canadian Dimension (Queer 2).

_600_400_90_s_c1.jpeg)