Queer liberation: the social organization of forgetting and the resistance of remembering

We need to reclaim the radical roots or our struggles in the new contexts we face

The first lesbian and gay rights demonstration on Parliament Hill, August 28, 1971. Photo courtesy of Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives.

For me one of the most exciting aspects of queer liberation was the recovery and remembering of our complex histories of resistance to oppression. Unfortunately, in much of the Left and within gay/lesbian communities our rich queer histories of struggle have been forgotten, creating a kind of social and historical amnesia. This forgetting has become one of the ways that a middle class, white, largely male, and moderate politics has been resituated at the heart of current gay/lesbian organizing that both moves us away from the radical roots of our struggles and towards accommodation with oppression and exploitation.

The Stonewall riots of 1969 are not often remembered as a major rebellion against police repression leading to the formation of Gay Liberation Fronts that were named partly in solidarity with the Vietnamese National Liberation Front then fighting against US imperialism. Instead, Stonewall has become the occasion for celebrating a limited commercialized and commodified gay (and to some extent lesbian) culture during Pride events.

We need to ask who is included and excluded from these constructions of gay pride? While white, middle class men and non-trans people are included, most of the rest of us get excluded and marginalized. The mainstream gay movement seems to want nothing to do with the left, liberationist character of early organizing efforts. The radical roots of queer liberation get in the way of the new middle class “homonormativity” that no longer challenges capitalist social relations or builds alliances with other oppressed people but simply seeks acceptance into heterosexual middle class respectability. Our histories of struggle have been systematically forgotten.

The 1969 reform

The 1969 criminal code is often misunderstood as when Pierre Elliot Trudeau legalized homosexuality. It was actually a limited and partial decriminalization. What is not often remembered is that the 1969 reform instituted a new form of public/private policing of queer sex. This led to an escalation of sexual policing including the pre-Olympic repression and clean-up campaigns in Montreal and Ottawa during 1975-1976, as well as the bath raids using bawdy house laws across Canada in the later 1970s and 1980s. It was these bath raids that produced the rebellions in the streets of Toronto during 1981 that helped to produce the massive expansion of gay community formation in that city. This reform also legislated a differential age of consent set at twenty-one to, supposedly, provide added protection for young men from the temptations of homosexual sex. This enshrined gay sex as some sort of special danger for young men. We still live with this legacy today with the age of consent set at eighteen for anal sex in much of Canada.

It is worth remembering how some early gay activists, such as Doug Sanders, viewed this reform. For him the 1969 reform,

[T]akes the gay issue and describes it in non-homosexual terms. [Decriminalization] occurs in a way in which the issue is never joined. The debate never occurs. And so homosexuals are no more real after the reform than before… I felt that an issue had been stolen from us. That we had forgotten that the reform issue was an issue that could have been used for public debate and it had been handled in such a way that there had been none. There has been a lot of forgetting here as well.

The social organization of forgetting

A social organization of forgetting also occurs through the support that some gays and lesbians give to national security campaigns in the “war on terror” with its major impact on queers of colour. After all, queers were central targets of the Canadian national security campaigns from the late 1950s through to the 1990s leading to the purging of thousands of suspected gay men and lesbians from the public service and the military.

The ideological practice of national security was used not only to expel queers from the fabric of the “nation-state” but is now used to expel some people of colour from the “nation-state.” Forgetting this social experience leads to not remembering the deeply rooted character of heterosexism in Canadian state and social formation. These national security campaigns were not a homophobic mistake made by a few RCMP officers. They were a central part of producing the social relations of the closet facing queers working for the government.

This social organization of forgetting is one of the crucial ways that ruling relations work to hinder our remembrance of past social struggles that won the social gains, programs, spaces, and human rights that we so often take for granted. We have been forced to forget where we have come from, our histories are rarely been recorded, and we are denied the embodied social and historical literacy that allow us to pass down knowledge, relive our pasts and, therefore, to grasp our present.

Moreover, this is how strategies of respectability gain hegemony strengthening middle class formations within queer communities. Given the anti-queer history which continues to shape our historical present, a more profound social transformation is required than winning marriage rights. Telling stories of queer resistance is an act of rebellion against the national security regime. We can resist this social organization of forgetting.

Two stories from research Patrizia Gentile and I have engaged in for our book The Canadian War on Queers: National Security as Sexual Regulation (UBC Press, 2009) remind us of the resistance of remembering.

“Wine, women, and song”

Sue (a pseudonym for one of our research participants) describes experiences in the militia and at military camp in the later 1950s in defying base regulations:

The deal was you were supposed to go out with men. So what we did was at military camp we went out with the men in the early part of the evening, and then because we were very virtuous young women we said, “Oh, we have to go home early.” And the military being very accommodating said, “This is where the women sleep, this is where the men sleep.” We said, “Fine, that’s cool, we’ll go back with the women.” … What we used to do, we dykes, we would want to go out and party. And we would take our bunk beds and we would fill them with pillows. And then we would say to the heterosexual women, “We really want to meet Charlie.” We would lie to them and they would cover cause they thought we were goin’ out to meet men. We were goin’ out to meet women. But we had it set up at the back of the barracks, and took over this room. We barricaded it from one side and then we had women on the other side guarding it, cause that’s where we were with Charlie. But they never saw Charlie! So here we had all these straight women, guarding us and guarding our beds and making sure that the authorities never knew we were out. And we weren’t supposed to be.

Turning the tables on the security police

David (also a pseudonym) tells us:

We even knew occasionally that there was somebody in some police force or some investigator who would be sitting in a bar… And you would see someone with a… newspaper held right up and if you… looked real closely you could find him holding behind the newspaper a camera and these people were photographing everyone in the bar (May 12, 1994).

David is speaking about his experiences of police surveillance in the basement tavern at the Lord Elgin around 1964, one of the major gathering places for gay men in Ottawa. Surveillance was one way that the RCMP collected information on homosexuals during the Canadian cold war against queers.

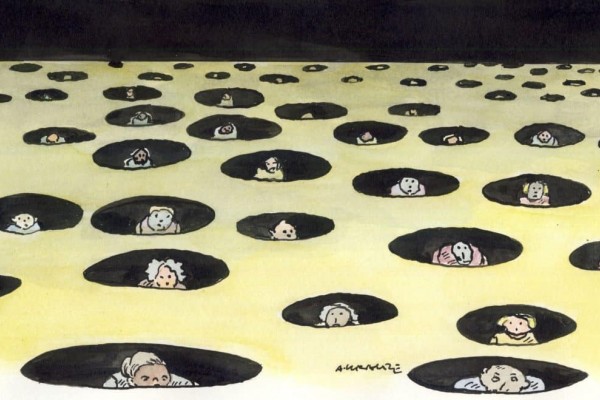

Rather than diving under the tables or running for cover these men exposed and turned the tables on the undercover agents. David’s story reveals not only the national security regime but also the resistance to it during the 1960s.

These practices of resistance caused problems for RCMP surveillance and forced them to shift their practices since they could no longer count on previous gay informants giving them information on others. They were compelled to rely on local morality squads to procure homosexual informants, as well as on the development of the “fruit machine” detection technology that never did work. These stories of resistance are very informative in fleshing out the social organization of the “non-cooperation” mentioned in RCMP texts.

Queers and the left: Remembering the connections

This also reminds us of the connections between queer revolt and left-wing radical organizing and of the radical roots of queer organizing. In the 1970s, RCMP surveillance was extended to cover gay and lesbian organizations as they emerged as an obstacle to the national security state. They also surveilled early queer groups because members of left groups like the League for Socialist Action, the Young Socialists, and the Revolutionary Marxist Group were involved in gay and lesbian organizing. For instance, the RCMP was led to doing surveillance on the first gay demonstration on Parliament Hill in August 1971 through their already existing surveillance of the League for Socialist Action. These important connections with the Left are not remembered in our historical present as these ties have been actively severed. Remembering and recovering these connections is vital for all who wish to rebuild connections between radical left and queer organizing.

We need to reclaim the radical roots or our struggles in the new contexts we face. Past acts of resistance can be an important resource that we draw and build upon in our contemporary struggles. We need to reignite radical queer liberation movements to challenge all the remaining forms of heterosexual hegemony we face and all the ways our oppression is bound up with capitalist class, patriarchal, racializing relations and other forms of dominance. In doing this, a passion for remembering our resistance can be a very useful antidote to the social organization of forgetting.

Gary Kinsman is a Canadian sociologist. Born in Toronto, he is one of Canada’s leading academics on lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender issues.

This article appeared in the July/August 2010 issue of Canadian Dimension (Queer 2).