Political openings: Class struggle during and after the pandemic

One in seven small businesses in Canada are at risk of closing permanently as a result of COVID-19 in addition to the ones that have already shuttered. Photo from Pixabay.

For some on the left, the economic breakthrough brought on by the pandemic was the general consensus, not least among economists, for an astonishing increase in fiscal spending. Relative to the economy’s size, the stimulus introduced so far in the US is already double (in Canada triple) what it was during the 2008-09 crisis, with more to come. And the stimulus in that earlier crisis was the largest since the Second World War, leading the OECD to declare that the earlier intervention “now seems like a small-scale rehearsal for the [present] disruptions to our socioeconomic system.”

The insistence by the adherents to Keynesianism and Modern Monetary Theory that there is generally more room for increases in public spending than governments let on, especially during deep crises, is valid. Their conclusion that something fundamental and perhaps permanent has changed in terms of looser spending constraints is seductive—it would indeed make things easier if all that was needed was to elect the right people and have them print money to meet popular priorities. But this obscures the most basic political questions of class and power under capitalism.

Spending our way to the good society?

Though central banks can lever the supply of money, this still depends on reverberations throughout the private sector. Financial institutions must want to lend, and so, generate an increase in the effective money supply. Corporations must want to borrow and invest. The alternative of the state itself doing the spending, and thereby replacing private institutions in choosing and carrying out priorities, directly challenges capitalism’s foundations—taking us a good deal beyond simply gearing up the money presses.

Moreover, the apparent contradiction between earlier pressures to restrain fiscal expenditures and the current profligacy actually includes an underlying consistency: reproducing the conditions for capitalist success. The shift to the high levels of government spending didn’t signal a permanent new paradigm for running a capitalist economy. It wasn’t the result of organized pressure from below or a sudden moral or conceptual conversion at the top. Rather, it was primarily imposed by the nature of the crisis and the conservative goal of returning to the earlier trajectory.

There is in a sense not one ‘bourgeoise’ economics but two: one economic theory or logic for normal times and another, with different tools and mechanisms, for times of deep crisis. The pandemic could only be overcome through temporarily keeping workers away from work, which required giving them funds to survive without employment (a contrast with 2008-9 when subsidies generally ignored ‘main street’). And the business infrastructure could only be saved for a ‘later’ revival with more loans and handouts. It was these two factors—keeping workers at home and businesses liquid—that brought on the remarkable degree of fiscal stimulus.

At bottom, how societies determine the allocation of their labour and resources—who is in charge, what the priorities are, who gets what—rests on considerations of social power and corresponding values and priorities. Transforming how this is done is conditional on developing and organizing popular support for challenging the private power of banks and corporations over our lives and with this, accepting the risks this entails. Controlling the money presses is certainly an element in this, but hardly the core challenge.

The present stimulus may indeed continue for a while. The fear of a second infection wave, the related fragility of the economy, and a concern, as well, to contain heightened social unease may be enough to sustain the stimulus through the rest of this year and perhaps the next. Moreover, the electoral costs to parties of the center-left of their past complicity in austerity teach the priority of limiting fiscal restraint as part of winning back and consolidating their former base. This may further support the unprecedented levels of fiscal spending for a period that extends into the likely Biden presidency.

But as a semblance of normality returns, so too can we expect the prevailing economic logic to again revert to orthodoxy. This will bring intense pressures to address a fiscal deficit swollen by the unusual steps taken during the extended health crisis, especially when even more spending will be called for to address decaying infrastructures, revealed social needs, and revived attention to the environmental crisis. The choices will by then be stark, even in the United States with its privileges of being the home of the world’s currency of choice.

US finance will warn of uncertainty and threaten to leave. Even if this threat is overblown, it will matter. Foreign investors will call on the US to get its house in order or see a fall in the dollar. Corporations will worry about inflation, higher interest rates to attract or retain foreign capital, and higher taxes to offset the growing debt. The dollar may, as it is now doing, fluctuate erratically. All of this, business will ‘advise,’ will bring a reluctance to invest until the future—their future—is more settled. The lifespan of the current spending consensus is consequently limited (noises to this effect, though still subdued, are already surfacing).

This is not to suggest there are no options. Rather, it’s to warn that the post-pandemic situation is likely to choke off the middle ground of spending the US into a happy republic. This will force a choice: will governments advance a far more radical approach in the redistribution of wealth and private economic rights and power, or will they retreat to once again hammering working people? The center may have moved, but even if Biden and the Democrats are generally reluctant to again impose austerity on working people, it’s hard to imagine that those who worked so hard to defeat the threat Sanders represented to the party establishment will, when confronted with difficult and polarized options, have the courage or will to choose the radical alternative.

This holds out a new threat. For the left, the primary lesson of Trumpism isn’t that Americans are racists (though some certainly are). Rather, it’s that if the government and institutions of the day don’t speak to popular frustrations, explain their roots, and channel them constructively, the right will mobilize the discontent destructively. A repeat of the Democratic Party’s policies of the recent past risk not only more harm to working people but also a repeat of new Trump emerging down the road – this time perhaps less clumsy and therefore even more dangerous.

A fundamental crisis in capitalism?

A more radical current on the left begins its analysis of the present moment by arguing that the economy was already in deep trouble before the pandemic; the pandemic only aggravated that crisis (for a sophisticated defense of this position see the work of Michael Roberts). Debating this is not an academic distraction. How we assess the contradictions of our era carries differing implications for expected scenarios and strategies.

For example, if the operating assumption is that we’re in a period of deglobalization, we might expect competitive pressures on the working classes to abate, with increased space for a new confidence and militancy. If capitalism is characterized as being on the verge of collapse, the central concern might be to patiently prepare for picking up the pieces. If we interpret the US economy, in particular, as a basket case, some may take this to mean that some kind of rebellion is imminent. If we anticipate a new era of inter-imperial rivalry, then an intensified nationalism might further divert workers from a class politics.

There is often, in such negative readings of capitalism’s current economic arc, an unstated political hopefulness about the response of the working classes. Capitalism’s problems will, such observers argue, make workers more receptive to a radical alternative. This ‘pessimism of the economy’ and ‘optimism of the resistance’ is, however, an unconvincing basis for assessing present openings.

Globalization may very well slow from its recent over-heated pace, but transnational companies are not going away; foreign supply chains, trade, and foreign investment are not about to be marginalized in corporate strategies; finance is not going to withdraw from its international presence. Capitalism may have been heading for a downturn before the pandemic, but a ‘downturn’ is not a ‘crisis’—the past century has witnessed many such downturns. Recovering from the pandemic will certainly be fraught and drawn out throughout the world, but a difficult transition does not necessarily threaten the economic system as a whole.

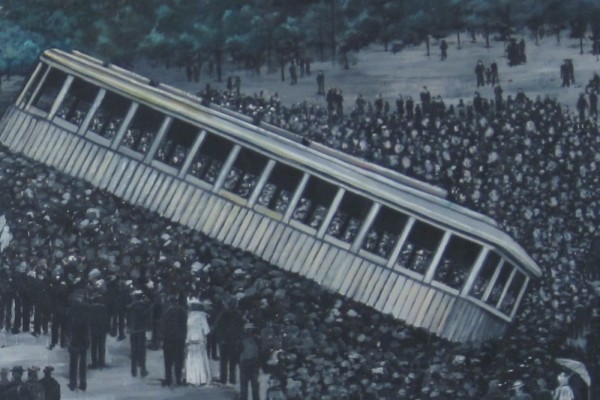

“3rd World War,” by Angel Boligan, El Universal, Mexico City, www.caglecartoons.com.

As for US-China rivalry, there will certainly be on-going geopolitical tensions, even very menacing ones; the making of a globally integrated capitalism is not a ‘tea party.’ Yet even under Trump’s confused and inconsistent policies, the extent of the integration of the two dominant global economies makes analogies to earlier imperial rivalries inapt. It is telling that for all the rhetoric and tit-for-tat to date, the trade conflicts have been primarily channelled into US pressure for China’s economic liberalization in terms of opening China up to US tech and finance firms, while the main concern of China has been that the US act less erratically and more ‘responsibly’ as a world leader.

In any case, the impact of negative economic results on resistance is not so straightforward. A troubled economy may very well undermine rather than strengthen worker confidence and militancy. Many working-class families, exhausted from trying to cope with the crisis, may be more amenable to fixing capitalism’s problems, even if it includes some further pain, than with looking to the uncertainties of capitalism’s collapse. They may, in light of recent insecurities, even be grateful for a return to a near-normal that, whatever its problems were, no longer seems all that bad.

None of this is to deny that there is a crisis in capitalism. It lies, however, on a different plane than the system’s ability to make profit for its stockholders, reward executives handsomely and penetrate every corner of life and of the globe. It is rather the conditions and consequences of capitalism’s successes in these terms—the sustained failures of capitalism to address popular needs, hopes, and fears as it commodifies nature and human activity—that defines the actual crisis as one that is not primarily economic but a matter of social legitimacy.

As the responses from parties and states to the rising discontent proved wanting, the crisis of legitimacy grew into a political crisis. Alongside popular anger with policies like free trade and austerity has come a loss of confidence and faith in state institutions ranging from social agencies to the judiciary and the police, along with disenchantment and alienation with mainstream political parties. It is on the terrain of social delegitimation and such political instability that capitalism’s vulnerability lies.

Strategic dilemmas, political openings

The pandemic, it is now commonly noted, further highlighted capitalism’s social irrationalities. This was especially so in the US with its stunted (though very expensive) health system and in Trump’s crass response to the relative weight of commercial versus health concerns.

To this opening for building a radical opposition was added the environmental connection. Though largely pushed to the side during the pandemic, COVID-19 served as the canary-in-the-mine for capitalism’s general unpreparedness for not only future health pandemics but also the infinitely greater environmental crisis already enveloping us. Unlike health pandemics, the environmental crisis can’t be resolved through lockdowns, social distancing, and vaccines. It demands a radical restructuring of how society is organized, what we value, and how we relate to each other—issues that dwarf the already traumatic experiences with Covid-19.

How, for example, will we respond if a worsening environment forces people in the global south off their land and brings mass migration to the more developed world? Do we even have the planning capacity to deal with internal mass migration if floods and droughts start occurring within our own borders? Can we really expect that people would heed calls for consumption restraint when the excess consumption of the rich so clearly translates into starvation for the poor and lower-income groups? The health pandemic gave states emergency powers, but they were, in general, only moderately applied; what kind of emergency powers would environmental collapse require and how could this be balanced by democratic checks?

A third opening broaches the pandemic’s potential impact on class formation. Nothing is more important than breakthroughs at this level, since creating the social power to actually change circumstances takes us beyond lamenting unfairness, expressing moral outrage, or sinking into a debilitating fatalism. In this regard, the combination of front-line workers facing intensified health risks, and the unique degree of public empathy for their work, has raised the prospect of a new militancy erupting within unions alongside a surge in new unionization in key sectors, each reinforcing the other.

The protests with the highest profile by far during the pandemic (and which were only partially an outcome of the pandemic) were those that erupted against police abuse and murder of Black people. The size of these protests, their energy, and widespread support from whites pose the question of whether this might now contribute to a broader left politics, one no longer haunted and diverted by racial divisions.

Adolph Reed Jr. has long argued that the way forward lies in expanding the frame of black politics to incorporate ‘the kinds of social and economic policies that address Black people as workers, students, parents, taxpayers, citizens, people in need of decent jobs, housing, and healthcare, or concerned with foreign policy [rather than] homogenize them under a monolithic racial classification’.

The other path, and for now perhaps the more likely one, is that the excitement and confidence generated by the protests reinforce a concentration on organizing around specifically ‘black’ concerns and the further ghettoization of black politics. The focus on policing is of obvious concern to blacks: their rate of incarceration is five to six times that of whites, and their likelihood of being shot and killed by police is roughly 2.5 times that of whites.

But something more than race is going on. The incarceration rate of American whites is itself generally more than double that of other rich countries, and in absolute numbers, police shoot and kill almost twice as many non-Hispanic whites—very few of whom are bankers or business executives—than blacks (from 2017 through mid 2020, 1441 whites were killed by police and 778 blacks). There is a policing problem in the US that stinks of racism but is also a broader class issue and one particular to the US.

Similarly, it is understandable that black activists point to the higher poverty rates in black communities and the wealth gap between working class blacks and working-class whites. But it would be a betrayal of the spirit of social justice that pervaded the protests if its ambitions were limited to ‘raising’ the conditions of poor blacks to the levels of poor whites, be they struggling single white mothers, whites coping with opioid addiction, or white workers laid off along with their Black brothers and sisters. Limited, as well, would be calling for working-class Blacks to match the wealth of working-class whites when sitting over both are the 10 percent of households that control over 70-75 percent of all wealth (sources vary).

The big question—the historic question given how impressive the June protests were—is whether a pivot will occur within this emerging movement toward creating the multi-issue black-white working-class alliances without which blacks (and whites) simply cannot win.

Strategic demands

What kinds of demands and campaigns might then contribute to building and spreading the understandings, networks, commitments, struggles, and structures that can realize the potentials flagged by life under the pandemic? We can expect the emergence of a wide range of mobilizations, based on differing demographics, regions, constituencies, and interests. But can we also identify a short and focused set of demands—not a wish list or a comprehensive program for a socialist government, but strategic demands that go beyond particularist concerns to contribute to the construction of a nation-wide movement to fundamentally challenge capitalist power?

Specific demands can only emerge out of widespread discussions. The demand for universal healthcare, its crucial importance all the more revealed through the pandemic, seems an obvious, common sense one. Yet the Democratic Party and some leaders of key unions have rejected it. This signals one arena of struggle that will undoubtedly occur within the broad left itself (never mind extending it to pharmacare and dental care and ending private control over the research and manufacture of drugs and protective equipment). To that, three demands, each strategically related to the new openings posed above, might be added.

One is the demand for a one-time emergency wealth tax. This is an unashamedly populist demand, intended to appeal to a broad swath of the population without addressing more fundamental issues of democratic economic control. A second is economic conversion, an unashamedly radical demand that moves beyond the generalities of the Green New Deal and the vagueness of a ‘just transition’ to engage workers in struggles that link the maintenance of a livable planet to the democratically planned restructuring of the economy.

Thirdly we need a push for greater unionization. The promise here lies not only in shifting the balance of power between specific groups of workers and their employers, but also in unleashing a long-awaited union upsurge with the potential to transform a working class consisting of fragmented and demoralized workers into a coherent social agent capable of winning and sustaining social change.

One-time emergency wealth tax

In the late 1980s the distribution of household wealth in the US (net worth minus debts) was already stunningly unequal, with the wealth of the top 10 percent of households having more than one-and-a-half times that of the combined wealth of the rest. By 2020, the top 10 percent increased their share to double that of all other US households. The shift was even greater for the one percent at the top of the American pyramid: at the start of 2020, 1.6 million American families had as much wealth as the 144 million households constituting the bottom 90 percent (see Federal Reserve, and Pew Research Center).

Such astonishing inequalities contradict any substantive notion of democracy. It perpetuates, through inter-generational transfer, future inequalities that are even less defendable. Rationalizing such inequality as the necessary ‘price’ of our rising standard of living has always been a feeble defense. It is especially so today, after three decades in which the top 10 percent grabbed 70 percent of the total increase in US household wealth at the same time as the quality of life for most Americans stagnated or deteriorated.

During the Depression, the top tax rate in the US went from 25 percent in 1931 to 70 percent at the end of the 1930s. At the beginning of the Second World War, it was increased to 81 percent, and in light of the war emergency and sacrifices ordinary people were called on to make, it was raised to 94 percent and an excess profit tax was introduced (today, by contrast, the top rate is just 37 percent). In that same spirit, the current moment of crisis, with its special sensitivity to inequalities and the massive and unwarranted affluence of the rich, calls for a decisive and radical reversal in the distribution of wealth.

To get a sense of the fiscal potentials of a one-time emergency wealth tax to offset the costs of the pandemic, consider the following example. If the top one percent were kept to their share of wealth at the end of the 1980s (one quarter of all wealth)—that is, if their wealth increased at only the rate of the total increase in wealth since 1989—this would justify a one-time average tax on their current wealth of 23 percent or some $7.5 trillion (which might be phased in over a few years to accommodate the process of cashing in some locked-up wealth so as to pay the tax).

This would, because of the overall growth in inflation-adjusted wealth, still leave the average household in the top one percent with more than triple the wealth they had in 1989 and the average wealth of someone in that top category some 89 times the average wealth of those in the bottom 90 percent (if an emergency one-time wealth tax of just one percent were levied on the rest of the top 10 percent, which would generate another $4 trillion).

To put this in perspective, the latest government estimates suggest a ‘pandemic deficit’ of some $6 trillion (i.e., the $4 trillion increase projected in the fiscal deficits in 2020 and 2021 over the pre-pandemic year 2019 plus an assumption of continued emergency spending while tax revenues lag). Or to use another comparison, Biden’s largest proposed budgetary item, the Green New Deal, is costed at $7 trillion over seven years. These are only illustrative, but they point to a significant one-time emergency wealth tax going a long way to overcoming the fiscal space lost in coping with the pandemic or for addressing essential programs.

No less important is the organizing significance of placing such an emergency tax on the public agenda. It would keep the inequalities in US capitalism in the public eye and those at the top of the pyramid on the defensive. It would also position the left with respect to future debates over ‘getting the fiscal deficit in order;’ if we were in the midst of exposing wealth inequalities and discussing how far to go with a new tax on wealth, elites might be in a bit of a bind arguing that the deficit is ‘unaffordable’ and there is ‘nothing to do’ but cut social programs and wages. And as argued earlier (see also Mat Bruenig’s convincing case in Jacobin), highlighting the class distribution of wealth shifts the understanding of a ‘black-white wealth gap’ into a ‘race-inflected class gap.’

There is, however, a limit to relying only on a wealth tax. As with simply printing money we cannot pretend that just taxing the wealth of the richest households will provide all the revenue we need. Middle income workers will also have to see their taxes raised. First, because there isn’t enough super-rich to finance all our expectations on an on-going basis. Second, because environmental pressures demand limits on the growth of private consumption, and taxes are a mechanism for limiting individual spending and channeling the funds toward collective services that are kinder to the environment, like education, healthcare, and public spaces.

Third, winning workers over to accepting a greater weight to public (collective) consumption is not just an environmental concern but a socialist one. Public consumption can further economic equality and involves a cultural change that speaks not so much to consuming less, but to consuming differently and, one would hope, better. Think, for example, of taxes securing better healthcare, water supplies, schools, libraries, public transit, parks, recreation centers, cultural activities, an end to poverty, and that myriad of universal services that would make it easier to look to more time off work as productivity increases.

Winning the working class to high taxes will not be easy, but it will be impossible without an especially high tax on the rich. Wealth taxes, such as an emergency one-time wealth tax, are therefore a condition of gaining broad acceptance for the taxes needed to pay for what we want from governments. Wealth taxes are doubly egalitarian: they take more from the rich (from each according to ability to pay) and, if distributed properly (to each according to need), the pool of taxes collected from both workers and the rich will disproportionately benefit the working class.

Conversion

The environmentalist movement has impressively raised environmental consciousness, and the Green New Deal has effectively placed the issue of massive environment-oriented infrastructural investments on the public agenda. Yet the call for a ‘just transition’ for those threatened with job loss generally has limited resonance amongst workers. Without the power to deliver on the promises, the demands come across as slogans rather than actual possibilities. And without linking the call for a fair transition to concrete struggles in specific workplaces and communities, the promise of a just transition is too vague to engage workers.

The dilemma we face is that, on the one hand, the urgency of the environmental crisis tends to push us to develop a mass base as quickly as possible. On the other hand, emphasizing that environmental advance will mean introducing comprehensive planning and taking on the property rights of corporations (you can’t plan what you don’t control) is something that risks limiting the base in the short run because of its radicalism and would, in any case, not be won except over an extended period of time. There is no short cut here; there is no way forward other than telling the truth, winning workers over to its implications, and developing a movement able to replace capitalism.

Directly related, popular demands are often too vague to engage workers; missing are concrete links to everyday struggles: the loss of jobs, the loss of the community’s productive capacities, addressing the potential of alternative production for social use (see the exemplary work of Green Jobs Oshawa). Without such engagement, it is near impossible to overcome the impact of accumulated defeats over decades that have not only lowered expectations of what can be achieved but even erased just thinking about alternatives.

The significance of a strategic emphasis on ‘conversion’ is that it links environmental issues to retaining and developing the productive capacities we will need for the environmentally sensitive transformation of everything related to how we work, travel, live, and play. It shifts the focus from the trap of looking to private corporations competing for global profits, to inward development, where possible, and applying our skills and resources to planning for social use. And it is only in engaging in struggles and campaigns that are both immediately concrete and national (and international) in scope, that it becomes possible to develop confidence in genuine possibilities.

The political demands this raises require new capacities largely undeveloped in the state’s historical record of coping with administration of a capitalist economy. Specific institutional proposals would include a) the creation of a National Conversion Agency to monitor closures and the run-down of investment to the aim of placing productive facilities that corporations no longer find profitable enough into public ownership and retooling them for social use; b) identification of markets for environmentally-friendly products and service through government procurement of the products; c) the creation of decentralized (regional) environment-techno hubs staffed by hundreds of young engineers exploring unmet community needs and mobilizing or developing the capabilities of addressing them; and d) establishment of elected community conversion boards to oversee the local economic transformations.

This brings to the fore again the question of financing. One dimension of a response is a levy on financial institutions for a fund to address environmental restructuring. Having bailed finance out in desperate times, such a levy is a reasonable quid pro quo. Yet if capital—especially highly mobile finance capital—is left with the right to move whenever it is unhappy, it also retains the blackmailing power to undermine democratically determined goals. Capital controls are, therefore, both a defense of basic democratic principles and a practical necessity.

Taking the questions of democratic participation and engagement seriously would mean mobilizing workers in their community or through their collective organizations. Labour councils would be encouraged to actively participate on the community environmental boards, and locals would be called on to establish conversion committees in workplaces, supported by research and funds from the national unions. These workplace committees would monitor the productive state of their workplaces, address what they were producing and what products they might produce, act as early-warning whistleblowers to check corporate environmental failures and inadequate investment plans, and use the mandate of the newly constituted National Conversion Agency to disrupt production when the social interest is at stake.

Unionization

Protests may surface via all kinds of struggles—student movements, fights for gender equality, anti-racist demands, immigrant rights, and so on—but as Andre Gorz famously noted (see Leo Panitch’s discussion of Gorz), the trade-union movement still carries, in spite of its weaknesses, “a particular responsibility; on it will largely depend the success or failure of all the other elements in this social movement.”

The ‘card check’ has been the main legislative change emphasized by unions: if a majority of workers sign up for the union, it must be automatically (legally) recognized. More radical steps would include banning any corporate attempt to influence workers’ decisions on unionization; banning, as well, the use of scabs to undermine workers on strike, a particularly critical measure in first contracts when unions have not yet had a chance to consolidate a solid membership base; and, given the general imbalance in employer-worker power, removing the prohibition against worker refusals to handle or work on goods shipped from a struck plant (‘hot cargo’).

The present moment could not be more favourable for pushing Biden and the Democratic Party to defend unionization and prioritize legislating the card check. The link between rising inequality and the decline in union density has been well documented, and various social movements have indirectly laid vital ground for unionization. This was the case with Occupy, which highlighted popular anger over how extreme income inequality had become. This was soon followed by the Fight for $15, revealing widespread support for lower-paid workers.

There is skepticism on whether Biden will come through on the card-check, which he had also endorsed as part of the Obama-Biden ticket but then reneged on. But there is also a question about the extent to which higher union density, in itself, would result in greater class consciousness or even effective unions. Canada currently has more than double the union density of the US, yet the labour energy is greater in the US. 60 years ago, the share of the US workforce in unions was almost triple its roughly 10 percent today. Yet unions weren’t able to block or even significantly moderate the subsequent context in which they operated (slower growth, more mobile capital, more international competition, more aggressive corporations, hostile governments).

The crisis in American unions lies in their general failure to effectively come to grips with those changes. What they now confront is not just the need to add members but also the need for transforming union structures and aspirations to the end of overturning the incapacitating context they confront. This does not negate the importance of legislation sympathetic to unionization—it is absolutely crucial—but it poses the hope that a legislative breakthrough (as opposed to various minor reforms) might be seized on by unions as a once-in-a-union-lifetime chance to reverse labour’s death by a thousand cuts.

In the 1930s, the United Mineworkers, fearing that if Big Steel weren’t unionized the miners would be isolated, sent some hundred organizers out to organize steelworkers into their own union. It is that kind of foresight and boldness that needs to surface once again. Only a virtual crusade could lead to the kind of dramatic leap forward essential to making unions into a confident and leading social force. Only through the ferment of an explosion in unionization might we see a reordering of union priorities and structures, the engagement of rank and file members in the struggle for unionization, and the emergence of new leaders and new blood. And if this leads unions to penetrate Amazon warehouses and Walmart distribution centers with all their disruptive power and bring workers as far apart as personal care workers and Google programmers into the organized working class, then the class as a whole will be strengthened.

It is fundamental that, if union leaderships do come to enthusiastically embrace the spread of unions, they do not ignore their own members. If they don’t first get their own members on side, the shift in resources and attention outward will be resented and undermined. If leaderships ignore the working conditions of their own members, especially in regard to workplace health and safety (which has gained such prominence since the pandemic) and unrelentless speedup, the drive to increased unionization will falter. Leadership must get and retain support from their members for moving on to organize other workers, with the added benefit that such high-profile struggles uniquely demonstrate to non-union workers that unionization really matters.

Buoyed by new enthusiasm and power, a revived labour movement could lead an upsurge against the social rot at the heart of the American empire:appalling inequality, permanent working-class insecurity, denial of the most basic needs like universal health coverage, stunted lives, punishing austerity, decaying infrastructure and, finally, the contrast between the liberating promise of technology and the confining reality of daily life. And it is that kind of example that can inspire young people—Black, white, Hispanic, Asian—to view labour struggle, once again, as where the action is. From there, unions could ambitiously move on to confront and reverse the economic context that underpinned their years of defeat: ‘free’ capital movements, corporate driven ‘free trade,’ the prioritization of ‘competitiveness’ over all else, and the distancing of life below from decisions made above.

From a ‘class-focused’ to a ‘class-rooted’ politics

Capitalism has, by and large, been successful in making the kind of working class it needs: one that is fragmented, particularist, employer-dependent, pressured by its circumstances to be oriented to the short-term, and too overwhelmed to seriously contemplate another world. The challenge confronting the left is whether it can take advantage of the spaces capitalism has not completely conquered and the contradictions of life under capitalism that have blocked the full integration of working people, to remake the working class into one that has the interest, will, confidence, and capacity to lead a challenge to capitalism.

This is primarily an organizational task. Policies matter, of course—there is no organizing without fighting for reforms—but the choice of policies to focus on, and the forms the struggle for those reforms takes, must be especially attuned to their potentials for organizational advance. The above emphasis on a wealth tax, for example, is based on keeping inequality in the forefront, and thus, creating fertile ground for mobilizing anger and raising more fundamental questions. The emphasis on conversion points to the necessity of radical economic and state transformations if we are to address our most critical needs. As well, it emphasizes the centrality of engaging workers in ways that can develop their understandings and capacities. The emphasis on unionization is closest to a policy directly addressing working-class power, but it too locates policy primarily in terms of it serving as a catalyst for transforming unions, not just ‘growing’ them, and so leads on to expanding future strategic options.

For the socialist left (see Searching for Socialism and The Socialist Challenge Today), in a context in which the only viable option for the time being seems to be to operate within existing political parties, the foremost task is how to manoeuvre through the institutional morass these parties inhabit and use the openings to support the most promising workplace and community struggles; restore a degree of historical memory to the working class; and contribute, through campaigns and discussions of lessons learned, to developing the individual and collective class capacities to analyze, organize, and act.

Out of this comes the most difficult undertaking: the project—cultural as well as organizational and political—of creating a new politics that, as Andrew Murray so clearly put it, is not only ‘class-focussed’ but is also ‘class rooted’. That is, the invention of a left agenda that is not just engaged in periodic working-class struggles but is also genuinely embedded in workers’ daily lives and committed to nurturing the best of the working class’s historic potentials.

Sam Gindin was research director of the Canadian Auto Workers from 1974–2000. He is co-author (with Leo Panitch) of The Making of Global Capitalism (Verso), and co-author with Leo Panitch and Steve Maher of The Socialist Challenge Today (Haymarket).

This article originally appeared on SocialistProject.ca.