Paul Kagame’s foray in eastern Congo leaves thousands dead and sparks fears of a broader war

Rwanda’s brutal assault on Goma has unleashed more agony for the Congolese, already traumatized by three decades of war

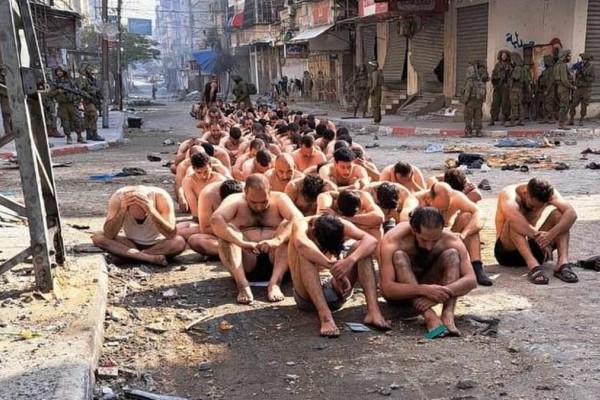

Members of the M23 rebel group ride into Goma. Photo by Sylvain Liechti/UN.

On the night of October 6, 1996, fighters loyal to Paul Kagame entered Lemera Hospital in eastern Congo and used bayonets and guns to kill patients in their beds. To inflict maximum misery, the attackers shot many of the patients through the mouth. Others managed to flee into surrounding forests with IV drips still dangling in their arms, only to be chased down, caught and massacred. Three nurses barricaded themselves in their living quarters on the compound when the attack began, but the killers smashed through the doors and executed two of them on the spot. A third nurse was forced by the attackers to drive all the medical supplies to a nearby village. The nurse was then murdered in cold blood.

It just so happened that Lemera’s chief doctor, Denis Mukwege, was not on site at the time of the attack, but his photograph and white doctor’s coat hanging in his office were riddled with bullets. Earlier in the day, he had taken a Swedish engineer with an infected foot to Bukavu, further north, to be evacuated to Stockholm to avoid amputation. As they descended into the main valley in Bukavu, Rwandan troops peppered their Toyota Land Cruiser with gunfire. It was a miracle they survived and made it to their destination.

“I could not have imagined that this was only the beginning,” Dr. Mukwege said as he accepted the Nobel Peace Prize in 2018 for treating thousands of Congolese women and girls who have been raped and mutilated in a gruesome war that has grinded on for decades and left millions of people dead.

“I have come to see [Lemera] as the beginning of an era of impunity for mass atrocities, and also as a symbol of the international community’s indifference in the face of such crimes,” the doctor, who has survived numerous assassination attempts over the years, said in a separate interview.

It defies imagination that the perpetrators of the heinous acts in Lemera were never prosecuted, that the victims were never truly honoured. It is even more astounding that Kagame, whose commanders ordered the operation against the hospital, has remained untouchable to this day.

Rwanda’s leader is the godfather of a succession of rebellions that have ravaged Congo—the biggest and most resource-rich country in Sub-Saharan Africa. And yet his main backers in the West have lauded Kagame as a visionary leader. His treatment on the world stage is mystifying for those who are aware of his actual record. But for his Rwandan and Congolese victims, Kagame’s unimpeachable status is nothing short of gut wrenching.

In Congo, Kagame’s wars are cyclical and the nature of his crimes are recursive. When his troops overthrew Congo’s longtime leader Mobutu Sese Seko in 1997, his Tutsi soldiers were accused of committing genocide against Congolese and Rwandan Hutu. The militias he has systematically sponsored ever since have eviscerated the social fabric of the Congolese nation.

For the Congolese, this latest killing spree has opened old wounds. Kagame’s military forces are currently controlling and steering a militia, known as M23, that has overrun Congo’s eastern provincial capital, Goma, where hundreds of thousands of displaced people had sought refuge from earlier fighting. A number of displacement camps on the outskirts of the city have been partially or completely emptied, according to UN officials, with families fleeing the fighting between Rwandan forces on the one side, and Congo’s army on the other. Congo’s military is shored up by UN troops, Burundian forces and a regional force comprised of soldiers from South Africa, Malawi and Tanzania. A record 17 peacekeepers, most of them South African, have recently lost their lives in combat. Burundi’s President Evariste Ndayishimiye has now issued a dire warning: “If Rwanda continues to make conquests, I know that war will even arrive in Burundi.”

Nearly 3,000 people have died, mostly civilians, in the latest round of fighting, and equal numbers have been wounded, according to the latest UN count. Goma’s streets are still littered with bodies, its morgue is overflowing and corpses are floating in Lake Kivu. Health officials and international NGOs worry about the risk of pandemics while food, water and medical supplies are running out. The fighting in its initial phase led to summary executions, bombing of displacement camps, reports of gang rape and other sexual violence. At Goma’s main hospital, the wounded lie on the floor waiting treatment, many of them children injured by shrapnel and explosives.

After seizing Goma, Rwandan-led forces and their political coalition sought to consolidate mineral-rich areas and surrounding supply lines, while advancing southward toward Bukavu, where Dr. Mukwege’s Panzi hospital is located. The Congolese government has called on young people in Bukavu to support the military and defend the nation. The M23 announced a ceasefire and said its forces did not intend to capture Bukavu, but then went on to seize the mineral-rich area of Nyabibwe in South Kivu on Wednesday.

While Kagame has largely relied on an international network of elites to shield him from political and legal fallout, his public image is definitely suffering. In an astonishing interview with CNN this week, Kagame said he did not know whether his troops were in Congo. His implausible deniability and nonsense fabrications were embarrassing, even for his ardent supporters. UN reports have documented the presence of several thousand Rwandan soldiers in eastern Congo, in particular in mineral-rich areas; UN investigators rely on satellites, authenticated photos, drone footage, video recordings, testimony and intelligence to provide evidence in their reports. Last year the UN revealed that Rwandan forces control and direct M23 operations.

It’s difficult to know why Kagame gambled on his troops seizing Goma now, a move surely to trigger an international outcry, at least at the UN Security Council. The Rwandan leader may be bent on testing the Trump administration’s resolve or lack of interest in Central Africa in order to pursue Rwanda’s territorial expansion in Congo, and consolidate control over areas rich in artisanal minerals.

With an estimated $24 trillion in natural resources, Congo is the biggest world supplier of cobalt, which is essential for powering modern technology, including battery operated vehicles. But it is Rwanda’s trafficking of Congolese gold and 3T—tantalum, tin and tungsten—and its export of these minerals along the global supply chain that has brought wealth to Rwandan oligarchs. This illicit trade has guaranteed a steady cheap supply of minerals for world markets, allowing processors, refiners and smelters to buy minerals directly from Kigali, and sell their products to big tech companies such as Apple, Intel and Microsoft. Congo’s government is readying a possible lawsuit against Apple, alleging that it has commercialized illegally exploited minerals, and that its key suppliers buy Congolese minerals laundered by Rwanda.

At the UN Security Council last week, Congo’s Foreign Minister Thérèse Kayikwamba Wagner called for an embargo on minerals exported from Rwanda, targeted sanctions against Kagame and his senior commanders, and an end to the UN’s use of Rwandan soldiers in peacekeeping missions. “This is not just about Congo. This is about humanity. You cannot get away with killing people for 30 years,” she implored.

The G7 countries has called on Rwanda and its M23 rebels to cease their offensive but has so far taken no concrete action.

For Dr. Mukwege, the world’s refusal to penalize Rwanda in the face of abject suffering of the Congolese people is despicable. “This horrible human butchery [in Goma] adds to the more than six million men, women and children killed in over three decades in these endless wars imposed on the Congolese people,” he said, adding that he condemns the complicit silence and inaction of the international community.

The Nobel Prize winner said the “exploitation of natural resources is the real crux of the matter.” He suggested there is a legal and peaceful way to produce and supply these resources to world markets.

The good doctor is right. We must remove Kagame’s incentive for waging war by stopping his violence and illegal trafficking. We need to slap an embargo against Rwanda, protect the Congolese people and put Kagame in the dock.

Judi Rever is a journalist from Montréal and is the author of In Praise of Blood: The Crimes of the Rwandan Patriotic Front.