Jason Kenney calls it socialist propaganda, but Mouseland has abiding relevance in Canadian politics

Last week, Alberta United Conservative Party (UCP) leader Jason Kenney took great exception to a children’s story session. Why, you ask? Because Alberta NDP Premier Rachel Notley chose to read kids the story of Mouseland, which was originally told by Tommy Douglas in the 1940s. The story of Mouseland—which can be seen here in animated form—described a society where mice formed the majority of the population, and yet consistently elected governments comprised of cats. Those cats—be they white cats or black cats or spotted cats—passed laws that benefitted them, often to the detriment of the mice majority.

The story turns for Douglas when a little mouse comes along with a bold idea, which is that instead of electing a government of cats, they should choose their leadership from amongst themselves. Of course, that little mouse was branded a dangerous subversive and was locked up, but as Douglas says, “you can lock up a mouse or a man but you can’t lock up an idea.”

The allegory is clearly meant to apply to Canadian society, and Douglas makes that explicit: “Now if you think it strange that mice should elect a government made up of cats, you just look at the history of Canada…and maybe you’ll see that they weren’t any stupider than we are.” For him, the story of Canadian politics was one where Liberal and Conservative cats ruled the roost while the masses of mice languished in poverty, precarity, and inequality. But when pioneering mice like J.S. Woodsworth stepped up to form the Labour Party and eventually the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, they offered a new path forward.

We could go on, but that’s the basic story of Mouseland. We can see why it would irritate Kenney, and when he calls it a socialist message, he’s right. But that’s anything but a knock on this fable. Rather, my view is that Mouseland remains instructive of our own political context.

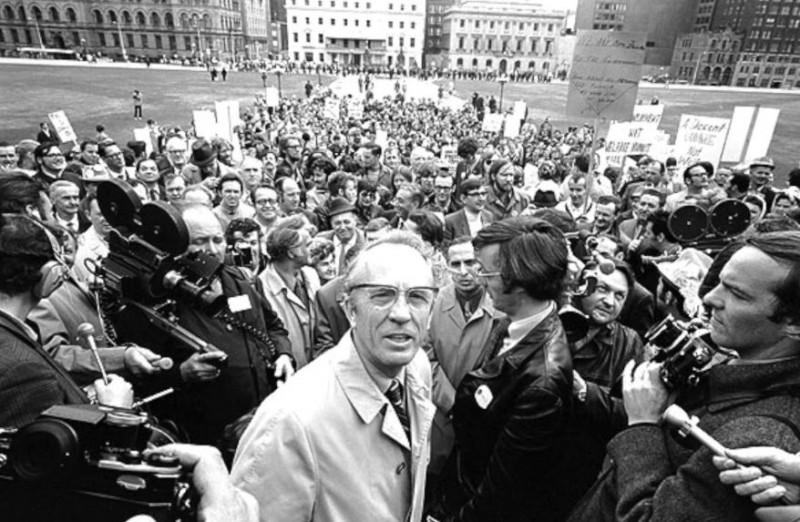

Animated edition of Mouseland by the United Auto Workers in the 1970s. The full comic can be found here.

First, the message of Mouseland is cast in a fairy-tale style, but it is very blatantly a story of class conflict and class interests. Douglas doesn’t go so far to say that the cats are bad—though they are cast nakedly as predatory upon the mice—but he does suggest that cats would pass laws that benefitted cats above all, and it didn’t matter which feline party was in power. The reality is that this state of affairs hasn’t dissipated, because the rich and powerful are overrepresented in our elected bodies, and even if subconsciously, are passing laws that benefit them and those like them. Simply put, the message of Mouseland remains clear: regular people must elect a government where they form the majority of seats, and wherein they can rule on their own behalf.

Second, and perhaps more timely, is that Mouseland is clearly a populist narrative. In our own times, many people, especially among the centrist elite, have equated populism with Trumpian far-right politics. Certainly, the right has been successful at tapping into popular discontent with the status quo, and has been able to portray wealthy leaders like Trump and Ford as regular joes. But as I’ve noted in other venues, populism is an essential component to any left-wing programme which sincerely seeks to represent the masses of working-class people. Mouseland is just the sort of fable that sparks a populist understanding of politics, where the 99% of mice stop deferring to the feline elite, and start doing politics differently. Where politicians who share their life experience are elected to represent them, and in turn can pass good laws—that is—laws that are good for mice.

One of the Canadian left’s key failings over the past couple decades has been a belief that we have to move beyond class conflict as a vehicle for social, political, and economic change; that regular Canadians don’t see themselves as mice anymore, or simply see themselves as cats-in-waiting. Some of this may well be true, but the reality is that class conflict isn’t going anywhere, and the social and economic elite understand this best of all. The left in Canada needs to centre politics of the many over the few, even if that makes enemies among the people unlikely to support them in the first place. Mouseland may well just be a fable, but it is nonetheless instructive, and can be used in part to illustrate a class consciousness among the masses of people in this country, matching that class solidarity which has never dissipated among the wealthy and well-connected.

A lot of this may be musing—and many of us will have strong disagreements about the specific path forward—but as it was said in Mouseland, “My friends, watch out for the little fellow with an idea.”

Christo Aivalis is an Editor of Active History, and a SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of History at the University of Toronto. He is also the author of The Constant Liberal Pierre Trudeau, Organized Labour, and the Canadian Social Democratic Left. His work has appeared in the Canadian Historical Review, Labour/le Travail, This Magazine, Ricochet, Maclean’s and The Washington Post. He has also served as a contributor to the Broadbent Institute, Canadian Press, Toronto Star, CTV and CBC. His current project is a biography of Canadian labour leader A.R. Mosher.